Almond Pollination 2008 and Beyond

Almond Pollination 2008 and Beyond

The Game Continues

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First published in ABJ Oct 2007

As I write this, it’s mid August, and a beekeepers thoughts turn toward almonds. Not the nut, but the beautiful blossoming trees, and especially their need for pollination. My friends in Chile and Australia have already moved their colonies to the orchards that bloom there six months opposite to ours. For those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, we’re at the year’s halfway point from the beginning of almond bloom. For a bee man, this is likely the best it’s going to get for the year. Our bees are at their strongest, and our colony numbers are likely at the maximum. It’s an uphill battle if colonies are not in good condition by mid August. One of my beekeeping mentors used to say, “If you want strong colonies for almonds, they’d better be that way by the end of August.”

Although it’s a bit early to make many predictions about the 2008 season, we’ve only got six months ’til bloom (less by the time you read this). Time to start gathering information, so we can make plans and commitments.

Information

What is the early outlook for the upcoming season? Just interview a bunch of large beekeepers, brokers, and almond growers, right? Well, you might as well go to a fisherman’s convention and ask about who caught the largest fish, and what were the best private fishing holes. You’d get all kinds of sincere answers, but you’d best take them all with a grain of salt! Commercial bee men are wonderful comrades, but they are also competitors. Putting a little bit of spin on an answer can work to their advantage, or help their image in a cutthroat business. It is generally to a commercial beekeeper’s advantage to say that their colonies are strong and healthy, and that they’re getting top dollar, but that everyone else’s numbers are down and it looks like there will be a shortage. Of course, no almond pollinator would wish bad luck on anyone they know, just on all the others that they don’t know!

The price for almond pollination is not set by any kind of reasonable bargaining arrangement between the beekeeping and almond growing industries, but rather by an ongoing auction in which price is set by supply and demand, on an orchard-by-orchard basis. The demand is fairly easy to approximate from the acreage planted to almonds; supply is an unknown that cannot be accurately determined until the colonies are actually inspected in the orchards in February. The main source of information is often rumor, which spreads as fast as cell phones can be dialed.

One of the most frustrating things about almond pollination is the volatility of the market. For the first twenty years that I took bees to almonds, we could count on the price going up about two dollars a year. In recent years, however, no one knew what the “going” price would be until December at the earliest, and perhaps not until February! Bees for pollination have a “time and place utility”—they are only worth something if they are in the orchard at the right time. A week earlier or a week too late, and they are worthless to the grower. Pollinators can’t just sit on their colonies, in the way that honey producers can sit on a warehouse full of barrels of honey, or the grower can sit on a warehouse of nuts (as both parties are doing at this writing). So things get crazy the last weeks before February 10th as growers and pollinators scramble to do business. Unfortunately, since the price is often not determined until the last minute, neither grower nor beekeeper can accurately plan their business.

Information is paramount, and all parties is hungry for it (thus this article). Peter Bray explained it eloquently:

“The one currency that is vital in marketing is information. Clear, factual and corroborated information. Smart operators run rings around you only where they are ahead of the game. FUD (Fear Uncertainty and Doubt) is the tool of the market disrupter. Accurate information is the weapon against FUD.

“Supply and demand ultimately is the determining factor for price setting. Accurate, timely and clear information is one of the few tools that the producer has at his disposal.”

From this point on, the game is going to be one of the growers claiming that they can’t afford outrageously expensive bees, and that “some other guy” is offering cheaper colonies. Growers will (accurately) point out that pollination fees have risen from 8% of their total cost of production, to over 20%. The beekeepers in turn are going to say that drought, disease, and too many new trees are creating a shortage, and that they need a fair price to stay in business, and besides, growers are still getting a good return on investment for every penny they spend on bees. Growers are over a barrel, since their year’s investment in the ranch will be lost if they don’t obtain bees. Beekeepers are generally up against a wall, in that they need to contract their bees to stay in business. Indeed, some beekeepers who were hurt by last year’s drought or CCD are barely hanging on. Another blow this year would bankrupt them.

Add to the game the “trust issue,” which was badly damaged last season. The drought in the Midwest had put the hurt on many beekeeping operations, and they were desperate for almond money to save their butts. Growers understood this, and were willing to pay high rental fees. Sadly, a number of beekeepers delivered high proportions of near-empty boxes, yet still accepted payment from an unknowing grower.

In one notable case, a grower contracted some 2000+ colonies from some northern beekeepers, and paid them upon delivery. The next day, he noticed that the colonies weren’t flying up to par, and quickly hired an inspector, who determined that the hives only averaged about two frames of bees (for those of you who are not mathematically inclined, a two-frame average implies that there were a lot of zeroes). The grower hurridly put a stop order on the $300,000 check. Word of this debacle spread through the growers, and soon inspectors were hopping from orchard to orchard, sometimes with similarly dire reports. A last-minute shuffle on “reserve” colonies ensued to provide adequate pollination, but a large degree of grower-to-beekeeper trust was lost that week.

Whether delivery of substandard loads is intentional or due to unexpected misfortune, any beekeeper that is caught charging for a load of dinks erodes grower trustfulness one more notch. Expect to see more grading, inspections, or other confirmation of colony strength this year!

The “reserve” colonies mentioned above are another interesting aspect of beekeepers playing the market both ways. Many large pollinators will contract out most of their colonies, but set aside a reserve for two purposes—to make up for dinks, or if they’re not needed, to put on the market at the last minute (at a premium) to supply desperate growers, gambling that the supply will be short.

Supply and Demand Economics

We are in the middle of a sea change shift in the bee industry. For the industry as a whole, 2007 was notable as the first year in which pollination income for bees exceeded the value of all honey produced. A series of coincidental events have brought this situation about. The worldwide appetite for almond nuts has skyrocketed, and due to climate, California is the place to grow them. Therefore, West Coast growers yanked out cotton and peaches, and planted almond trees, which now cover over 1200 square miles of the Central Valley. Unfortunately for the growers, as demand for bees to pollinate the massive new plantings rose, the nation’s supply of bee colonies plummeted. Thus a classic “supply and demand” situation arose.

However, this is not a normal supply/demand situation. In normal markets supply can expand to meet any demand. But we’re dealing with two unusual industries here. There is a strong market for almonds worldwide, but only a few places on the planet that have the climate, soil, and water to grow them, thus California’s 82% share of the world’s production. This limitation on production is likely to keep nut prices high, and demand for bees will follow. The bee supply side is similarly limited–if any other agricultural crop suddenly jumped in price the way colony rental prices have, a jillion farmers would start growing it until they had increased the supply to the point that it was barely profitable. However, not just everyone wants to deal with the stings, hard work, and driving entailed in commercial beekeeping, and this fact restrains any quick increase in available colonies.

The pollination market has turned into a “demand auction,” in which growers outbid each other to ensure that they got their share of a limited supply of bees (in the short term, what occurred was a near “vertical supply curve”—an essentially fixed supply of bees was being chased by growers desperate to get their trees pollinated. Beekeepers in essence have the growers by the short hairs, so to speak, since there are few “substitute goods” to replace honeybees for almond pollination.

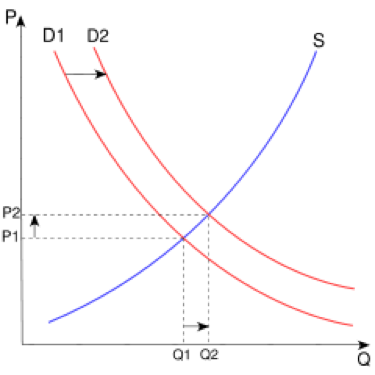

In microeconomic theory, price is set by the intersection of supply and demand curves. This intersection is called the “equilibrium point”–in the case of almond pollination, the average price (see illustration). Let’s put some realistic limits on the curves below, starting with the blue supply curve. At a price of $30 per colony, the supply of bees east of the Rockies would dry up, since the thirty bucks would barely cover moving costs, so this could be the low end of the blue curve. If the price were $300, every hive in the U.S. would have to be guarded, to keep it from being stolen and trucked to California (once they were all gone, the supply curve would go vertical at that point).

Looking at the red demand curves, at a price of $30, the curve would drop straight down at the right, once every acre of almonds had about three colonies. It would rise at the left until the marginal reward for spending an extra dollar on pollination will not be recovered by the value of the extra nuts produced. For older orchards (with operating costs of about $1100/acre), this figure is currently about $125 per colony for some growers—their banker won’t allow any more. For high-producing newer orchards (3500 lbs/acre), that figure might be in the range of $300 for the second or third colony. However, $900 (3 colonies at $300) would be nearly equal to the total of all other operating costs, save debt service on the land. Growers would have a tough time swallowing that bitter pill!

The price P of a product is determined by a balance between production at each price (supply S) and the desires of those with purchasing power at each price (demand D). The graph depicts an increase in demand from D1 to D2, along with a consequent increase in price and quantity Q sold of the product. From Wikipedia.

Last year, demand slightly exceeded supply, and prices for bees were up. Due to the previously noted poor-quality hives foisted upon some growers, the demand may be up this coming season for “graded” colonies, and down for “field run.” Demand will depend upon several factors:

Demand

By far the most important factor to consider in almond pollination is the wholesale price of nuts. There was a slight carryover of nuts last year, so demand is not chasing a limited supply. When nut prices approached $4.00/lb, the sky was the limit for what growers would pay for bees. At this writing, the asking price is in the $1.80 range, but not many are moving yet, as buyers continue to tap into their reserves. Informed sources expect this year’s crop to move at a dime or two less. Outlook is still good for sustained strong prices this year, despite an expected record crop (www.bluediamond.com/news/index.cfm?l_tableid=283), but pessimists are afraid that prices may head south toward $1.00 at some future date if the supply of nuts starts to approach demand.

In the long term, much will depend upon whether the Almond Board can continue to expand the market for nuts, and thus increase demand commensurate with the additional supply that will be produced by the new acreage coming into production. Pessimists note that there will be about 100,000 acres of new orchards coming into production in the two years following 2008. The obvious question is, whether there is a trainwreck coming as the expected increased production floods the market.

I recently spoke with one of the largest growers, and he was sanguine that due to the limited amount of agricultural land on earth suitable for almonds, coupled with the health and confectionary desirablity of the nuts, that a strong price could be maintained. If this proves true, it would be great for both of our industries! It will also give beekeepers the incentive to invest in increasing their numbers of colonies.

On the other hand, if nut prices do indeed drop, competition will get ugly. Low producing orchards will be pulled, and surviving growers will pinch every penny. Beekeepers will cut each other’s throats with price wars. So the Big Question is, is it wise to expand your operation now? Would it pencil out to be a worthwhile investment if you could only get, say, $80 per colony rent?

Net new acreage is again dependent upon nut prices. Older low-yielding orchards (1000 nut pounds/acre yield) will only remain profitable if nut prices are higher than some figure above $1/lb. If nut prices approach that low figure, the older orchards will be pulled. However, if prices hold as expected, there will be a net increase of approximately 25,000 acres of new trees coming into production in 2008, which will increase demand by approximately 60,000 colonies.

Some growers with older orchards are at their limit of what they can pay for pollination—constrained by their banker. But many are nursing a few more years out of their trees by cutting costs elsewhere (why yank your old trees if you’re afraid that nut prices will drop by the time that new replacement trees come into bearing?). Unfortunately, some are being forced to reluctantly give up longstanding relationships with their traditional beekeepers, who can find higher prices paid by the newer orchards.

Supply

Supply is “the quantity of goods that a supplier is willing to bring into the market for sale at any given price. The main point to remember is that it is the growers who are setting the price; beekeepers are largely passive in this, and are just waiting to see what the “going” price will be.

What we also are experiencing in the short term is a “backward-bending” supply curve. Since the price offered for colonies is so high, there is really little incentive for many established beekeepers to make additional increase, once they have all their inventory of boxes filled with bees—they make plenty of income with what they’ve got. Therefore, it will be up to new beekeepers, or those wanting to expand their operations, to bring about an increase in supply. This brings up the concept of “marginalist economic theory”—that the price of all goods will be the cost of making the last one that people will purchase. In this case, the question is, “What is the real cost of producing one more strong colony for the almond market?” This cost must include woodenware, bees, labor, feeding, transportation, winter losses, etc., as well as amortized overhead for forklifts, trucks warehouses, etc. Local beekeepers put that figure approaching $200, and want to recoup most of it the first season.

On the other hand, there are older bee operations that have already paid off the property and structures, and have stacks of fully amortized equipment, perhaps handed down by grandpa. As they say, the easiest way to make a small fortune in beekeeping, is to start with a large fortune. Some beekeeping operations are doing just this—renting their bees at a rate less than the realistic cost of replacement. In essence, running down their capital. What with the hard work, mite problems, and low honey prices, there are a number of beekeepers who just want to make some cash in California, sell off the business while prices are high, and retire.

If the above happens, we’re going to see more Western beekeepers adopt agribusiness practices, and shift to the feedlot model of beekeeping to supply the orchards. Feedlot beekeeping is considerably more expensive than letting bees feed themselves on abundant pasture, and those bees won’t be going into almonds cheap!

Of those beekeepers who did indeed make great increase, some overextended, and have found themselves and their bees stretched too thin, sometimes with disasterous consequences. Every crash takes a bite out of supply.

Mites and colony health

A number of beekeepers are “uneasy” about how their bees are going to look come November, let alone February. Mite control, poor forage, and disease are all issues.

There is a thin line drawn by a single miticide that keeps varroa at bay in most commercial operations. Unfortunately, the first mite that mutates to be completely resistant to it will likely go into the almonds. The rest of the story could get ugly.

Of perhaps greater import is the issue of Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). As I write this, colonies are collapsing in the Midwest. Other beekeepers are noting that some colonies are building unusually slowly, which could be an early sign of CCD. Press releases from Columbia University and elsewhere indicate that a subgroup of the CCD team may have found a virus associated with CCD. If this is the case, CCD could conceivably be an epidemic that has yet to fully run its course. By the time you read this article, more information should be available. CCD is truly a wild card this year!

Recent research indicates that our bees are carrying quite a load of viruses, and that parts of some viral genome has been incorporated into both the bees’ and mites’ DNA. This could prove to be either good or bad news (which do you want first?). The good news is that a small piece of viral material appears to confer a bee resistance to the virus, and in one small sample, 30% of bees . The bad news is that there is speculation that a larger section of viral

The forage situation is not getting any better overall. The Midwest appears to be moving into a warming, dry trend, and California is in a La Niña period. The ethanol boondoggle is encouraging farmers to cover every available acre with corn. Development is eating up locations. The Monsanto salesmen are convincing farmers that bare soil is beautiful. The increased use of leafcutter bees in the Imperial Valley is hurting honeybees. And the dairymen’s demand for “test” hay is resulting in early cutting of alfalfa before it blooms. Definitely not a pretty picture. Feeding pollen supplement is laborious and costly, and is an investment beekeepers will only make if they expect a return in the form of additional pollination rent.

Transportation costs and border issues

Fuel costs are up, making it more expensive to haul colonies long distances. East Coast beekeepers won’t be coming if the prices drop from last year’s.

Border inspection issues appear to be less noisome, as long as truckers hit the bug stations during business hours.

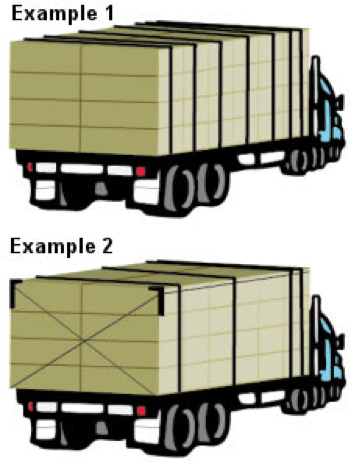

Example 1: Multiple Articles

1. 4×4-foot bins loaded with apples

2. 48 bins at 500 lbs. each

3. 4,000 lbs. per row, 24,000 lbs. total

Two straps first row (first 10 feet)

One strap each row thereafter

Each strap rated with a working load limit of 2,000 lbs.

(Examples for strapping of loads. Courtesy California Farm Bureau.)

California is implementing new laws for tying down loads to comply with Federal regulations. Beehives must now be tied down with appropriate crosswise ropes or straps (see illustration). Truckers run the risk of getting a safety citation that could cost them as much as $700 for violating the new law. However, that may be the least of their worries if the CHP forces them to park the load until they find straps to tie it off properly.

| Working Loads of Ropes (lbs) | ||

| Type Rope | 7/16” dia | 1/2” dia |

| Polypropylene | 525 | 625 |

| Nylon | 410 | 525 |

| Polyester | 750 | 960 |

| 1-3/4” | 2” | |

| Synthetic webbing | 1750 | 2000 |

| Source: http://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/rules-regulations/administration/rulemakings/cargosecurement.htm | ||

The Weather

Mother Nature has been kind to some regions, but savagely dry in others. Late rains in the Midwest salvaged some operations, but bees in parts of the South and California are starving.

Paradoxically, conditions were so good in parts of the northerly states this spring, that beekeepers couldn’t keep the dang bees in the boxes! I’ve gotten reports from bee men whose operations were decimated by excessive swarming. Sometimes you can’t win for losing.

The Honey Market

Honey producers keep waiting for the price to rise. Many of them have come to California only because of the low price of honey, or because drought decimated their honey crop. Moving bees to California is a pain in the butt (literally)–a beekeeper has to go out to his many honey locations and round up the hives, stage them, load them, stage them again, and on and on (as covered well by Bob Harrison previously). If the price offered by the growers drops, or the price of honey rises, a big chunk of supply will dry up, as honey producers stay home.

Other Sources of Bees

Last year Aussie package imports took up a lot of the slack in bee supply. If anything were to affect the importation of those bees, it would leave a big hole to fill. Furthermore, grower enthusiasm of package bees is waning. However, the packages can still be used effectively (but expensively) to boost weak colonies.

Frame Strength

Many pollinators find it a challenge to meet the 8-frame strength that growers wish for. Last year, many 8-frame promises were fulfilled with 4-6 frame realities. On the other hand, there are those beekeepers who manage to come up with 12-frame or stronger colonies. Despite plenty of evidence that those colonies should be worth at least three times the 4-frame price, growers are unwilling to pay that kind of high figure. So some beemen with premium colonies are simply dividing their strong colonies, for example, splitting two 12-framers into three 8-framers and making half again as much for the same number of bees! I call this the “Domino’s Model”–forget trying to make the best pizza, what the customer really wants is a standard pizza delivered on time at an affordable price.

The Price

If you ask a grower or beekeeper what price they’ve contracted bees for, you’ll hear only one figure—the highest price paid (beekeeper), or lowest contract (grower). This price may only reflect a small portion of their contracts, but they will generally neglect to mention the rest. It’s all about image, and playing the market. If I interview a large beekeeper, and he knows that I am going to publish the information he gives me, it is clearly in his best interest to tell me that all his bees are contracted at a high price, because he knows that others will then try to undercut him. In reality, he may eventually go in at a different price, but in the meantime, the market has been influenced by his disinformation.

So what kind of prices are being bandied about? One large broker is offering beekeepers $155+ for 8-framers. Paramount hasn’t set their price yet, but last year they paid beekeepers a bonus for colonies over 8 frames, for a price up to $145. Another broker paid up to $165 for superpremium colonies. Growers have shown little interest in 4-framers offered early at $120. The more optimistic clairvoyants are projecting that prices will reach $180 or higher, but this figure is tempered by a vast “silent majority” who are happy to place great bees at $125. The very high prices, and very low prices get a great deal of publicity, but it’s this silent majority that really sets the price! At the time of this writing, the $140-$160 figure appears to be the range that will encourage beekeepers to commit to early contracts to provide strong colonies, and not be too egregious to growers as long as nut prices hold. The last-hour price is anyone’s guess, since no one can possibly predict what the actual available supply of bees is going to be come February.

Last year, there was substantial “grower resistance” to price increases, and some cancelled longstanding relationships, and went shopping for cheaper bees. Not all found them, and some were unhappy with what was finally delivered. Amazingly, some growers waited until the last week before bloom before committing to contracts. They were convinced that a glut of colonies was going to materialize, and were damned if they were going to get stuck with “pricey” bees.

Stability in the industry would be encouraged by beekeepers and growers committing to mutually acceptible prices early in the season, rather than playing games at the last hour (unfortunately, this may be difficult to do in the current state of the industry, in which beekeepers often experience unexpected colony losses of 30% or greater losses). Large brokers Lyle Johnson and Joe Traynor both feel that contracts should be signed by September, in order to provide beekeepers the incentive to feed and manage their colonies for maximum health and strength, and to be fair to the growers.

Miscellaneous Tips

From Joe Traynor

We have seen time and again that bees shipped to CA from MT, ND and MN in October dwindle far more than bees shipped in late Nov.-Dec. We can have 90 degree days in October and no bee forage. Few beekeepers from the northern tier of states risk December deliveries (because of potential hazardous road conditions) but invariably bees that arrive here after the cold weather has settled in (in Dec.) do the best and the very last loads a beekeeper delivers from these areas fare better than the first loads.

From Bob Harrison 5/1

The biggest success from a long distance for southern beekeepers to almonds has been in making up singles by cramming a frame of honey , 8 or nine brood and so many bees you can barely get the lid on. These go right into almonds and have brought the full price. The beekeepers say they care little what they look like when they return as long as they get their equipment back as they will equalize the mess when they return.