Fat Bees- Part 2

Fat Bees- Part 2

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in September 2007

Now that we’re gaining an understanding of the role of vitellogenin in honeybee biology, how can we apply that knowledge to keep our bees healthier, to help them be more productive, and to improve the bottom line?

by Randy Oliver

The life of the honeybee colony is not all humming springtime bliss, with flowers aplenty, and the carefree image that the public imagines. For much of the year in temperate climates, colonies must ruthlessly compete with one another for resources, and then conserve their hard-earned protein and carbohydrate stores for lean times. As I detailed earlier, carbohydrates are stored as sugars in honey, and the reservoir for protein is largely in the form of vitellogenin carefully hoarded in nurse bees’ bodies.

The point that I’d like to make really clear to beekeepers is that you’re not managing white boxes–you’re managing the livestock within those boxes. Just as any rancher judiciously selects pasture for his stock, and supplements their diet with feed carefully chosen for its nutritional value, the beekeeper should do the same. However, with livestock it’s easy to see if individual animals are not growing well, or if their ribs are showing. It’s a bit more difficult to recognize protein deficiency in bees.

Protein is the key ingredient of feed. Every feed sack lists protein content first, since that’s the main thing you’re paying for. You can provide livestock with energy by feeding cheap corn, but if you want them to grow, the ration needs to have enough protein, and that protein must consist of the proper balance of amino acids. Years ago, I ran a feed store. I remember one old boy who came in each week to purchase sacks of rolled corn for his pig. He just couldn’t bring himself to pay the extra buck for the formulated “hog grower” pellets that contained extra protein, vitamins, and minerals. After dumping hundreds of pounds of corn into that poor pig, he finally realized that it just wasn’t going to gain weight unless he gave it a higher protein diet. He bought the right feed, and soon had a huge, healthy hog. My point? You’re not going to get strong colonies by just feeding ‘em sugar syrup!

As long as I’m on the livestock analogy, let’s talk about pasture. The “pasture” for your bees is the total area that they can forage over (they are obviously not constrained by fences or property lines). But that concept may be misleading. For a great read, pick up Bumblebee Economics by Bernd Heinrich. Everything about bee foraging involves the economics of energy expenditure vs. energy gain. Even though a bee is able to fly for two, three, or more miles to reach flowers, the time and metabolic costs involved to traverse such distances may result in meager net returns. The most productive foraging is done within a half mile of the beeyard—an area of about a square mile.

In nature, you’ll generally find only a few colonies per square mile in productive areas. As soon as we start packing 24, 100, or more colonies into a beeyard, it is no longer a natural stocking rate. It’s not hard to exceed the “carrying capacity” of the pasture. Now some areas may be so productive for a few weeks during the major bloom that a hundred colonies could produce a bumper crop of honey. But before or after that bloom those colonies will be competing with one another for precious resources. When competition is tough, the stronger colonies have the clear advantage—big colonies can store honey while weak colonies in the same yard are starving.

These points may be moot to the hobbyist with a few colonies. Indeed, urban and suburban settings often provide excellent extended forage. The irrigation of ornamental landscapes in dry areas, and the extended season due to urban warming in cool areas are both beneficial to bees. Here in bone-dry California, the best late summer yards are often on the edges of towns.

I live in the Northern California foothills. Just below me, in the northern half of California’s great Central Valley, live some of the best beekeepers in the world—the California queen breeders and package producers. There are dynasties of beekeeping families here. These guys teethed on hive tools as infants, and received smokers for their first Christmas presents! They make a living in an area where it may not rain a single drop for six months straight during the summer, and beeyards are so close that you can stand in any one and hit the next one with a thrown rock. They are ahead of the curve on the subject of feeding bees, and have been greatly aided for many years by our stellar Extension Apiculturist, Dr. Eric Mussen. One of their own, Bob Koehnen, introduced the concept of “feedlot beekeeping,” and the practice has been widely adopted.

Feeding bees

First, a hobby beekeeper may never need to feed a colony. The only time that many hobby beekeepers will ever need to feed is when they are helping the bees draw out the combs of foundation in the broodnest for the first time. Feeding is a real pain! I spent years developing a migratory schedule that allowed me to never feed a single drop of syrup or supplement, yet still take super strong colonies to almonds each spring. It is generally more cost effective for me to move my bees to better pasture, than to feed them in place. However, I run a “niche” beekeeping operation, and am geographically located in an area that allows me to follow the bloom up the slope of the Sierra Nevada mountains each year. Many California beekeepers move out of state for the same reason each summer.

Traditionally, beekeepers “fed” bees light sugar syrup in the spring to stimulate the queens to lay, and heavy sugar syrup in the fall for winter stores. This is low tech, no-brainer “feeding”—I put the word in quotes because feeding sugar syrup to bees is like saying that you’re “feeding” your growing child by giving him a Coke. Sugar syrup can be an important tool in bee management, but don’t expect it to do more than it can. That said, sugar syrup can give a lot of bang for the buck. It’s cheaper than honey, and stimulative feeding of light syrup not only changes their behavior, but can save the bees an incredible amount of effort in foraging for nectar, thus allowing them to focus their energies on other tasks—such as comb building, pollen foraging, or keeping the cluster warm. However, feeding syrup to a colony without a pollen flow may be counterproductive—if the bees are forced to dig into their vitellogenin reserves, you may actually increase colony protein stress. I’ll cover sugar feeding next month.

Pollen supplements

OK, let’s get to the “meat” of the issue–protein. Bees obtain their protein from a mixture of plant pollens. The mixture is critical, since the amino acid (and fatty acid) composition of pollens varies greatly. Any time that colonies of bees that are rearing brood do not have access to a mix of nutritious pollens, you can assume that they are under protein stress. The clearest indicator of adequate protein intake is that the colonies will be rearing drones. They will rear drones any time of the year (if the weather is warm enough) that there is ample pollen available. Observe the foragers returning in the morning to see if they are bringing in plenty of pollen loads of various colors. Other signs that would make you suspect a protein deficiency are a lack of a “pollen ring” around the brood, or slow buildup.

What can you do about supplementing them with pollen? The best supplement is previously trapped pollen from your own (or another trusted) operation. Unfortunately, stored pollen loses its nutritional value fairly rapidly. It should be frozen, or fermented into “bee bread” by lactic acid fermentation as bees do in the combs. This process is similar to the methods for making silage, sauerkraut, and yogurt. Sources for detailed instructions are in References.

If you can’t trap your own pollen, you can purchase irradiated or ethylene oxide treated pollen in bulk (treatments are to kill disease spores). Chinese pollen is cheapest, but there are questions about pesticide contamination. So far, though, I haven’t heard of any problems with it.

What beekeepers really want is a pollen substitute—a cheap, dry formulated feed, just like any commercial animal ration, that is nutritionally complete. Unfortunately, despite years of research, I can’t say that there is a true pollen substitute on the market (although some of the formulations come close). The telling point is that all formulas so far are improved by the addition of natural pollen. Early efforts by Dr. M. H. Haydak found that soy and yeast were economical protein bases. A later series of experiments by Drs. Herbert and Shimanuki elucidated details about vitamins, minerals, and sterols. The major bee suppliers offer proprietary pollen supplements. The new kid on the block, FeedBee, was just reformulated. And Dr. Gordon Wardell is about to release MegaBee, developed in conjunction with the USDA Agricultural Research Service. Dr. Wardell is trying to develop the “Holy Grail” of bee feeds—a liquid bee diet that could be fed as a syrup.

Many commercial beekeepers mix their own supplement. If you wish to try it, here are some tips:

1. Supplements are mixed from a protein base (usually soy or yeast), sugar, and whatever “special” ingredients the chef feels are necessary. All components must be very finely ground for the bees to be able to digest them. Freshness is critical—yeast and pollen lose their nutritive value with extended storage, and old soy flour may even become toxic to the bees!

2. Soy flour (“fluff”) provides a nice texture to the patty. Expeller processed soy is best, but due to potential toxic sugar and taste issues, stick with a proven product sold by a bee supplier. Soy milk is another possibility. For what it’s worth, the Dadant branch in the heart of the North Valley can order soy flour, but doesn’t get much call for it.

3. Brewers yeast is generally added as a B vitamin source, but can be feed alone. Many California beekeepers feed a yeast/natural pollen/syrup blend. True brewers yeast from beer may be of more consistent quality than yeast derived from other processes. Again, stick to a proven brand. There are other yeasts and yeast products, but brewers yeast is likely the most cost effective at this time.

4. The protein level of the supplement should be about 25% (dry weight, including sugar). A mixture of protein sources may help to balance the amino acid ratios.

5. Bees like sweet patties, and take them best if sugar level is at least 50% (dry weight).

6. There should to be some fats or oils, but this has not been well studied (I’m experimenting along this avenue this summer). These fats supply necessary lipids, and also have antimicrobial and phagostimulatory qualities. They also improve texture.

7. For extended broodrearing, bees require a cholesterol source. Dried egg will supply this. Egg is also a high-quality protein, and can be a substantial portion of the mix. We’re experimenting with this now.

8. Sodium and ash levels should be low, potassium level relatively high. Starch should not exceed 3%.

9. Be careful with vitamin or mineral additives—commercial blends are developed for mammals, not bees.

10. Acidifying the mix with citric acid and vitamin C may be beneficial.

11. If you really want to get into it, some lactic-fermented pollen or other probiotic (when they hit the market) might be a beneficial addition. The bacteria in these “charge” a bee’s gut, and may help with disease resistance.

12. Remember, you are likely making a pollen supplement, not a substitute. If some natural pollen is being gathered, your formula is not as critical, and straight yeast or soy may suffice. Many beekeepers add 5% – 10% natural pollen to make up for any nutritional deficiencies, and to act as a “phagostimulant” (something added to make them want to eat it).

13. A commercial mortar, sausage, or dough mixer works great for mixing large batches. Allen Dick offers a free spreadsheet download to calculate protein and sugar content, and cost per pound of whatever recipe you use (see References). Thanks, Allen!

Feeding tips

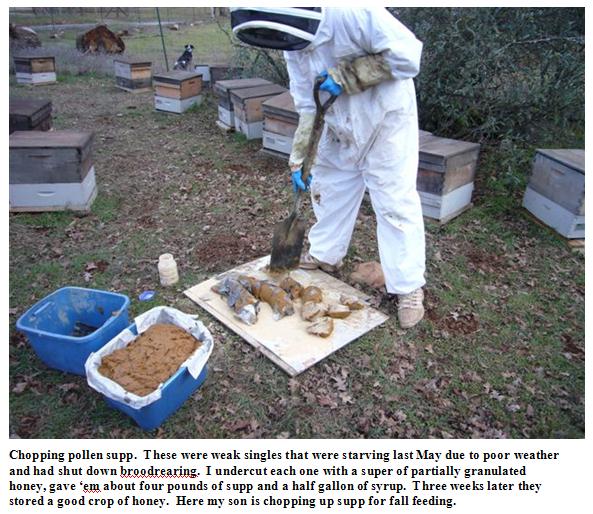

1. You don’t have to feed “patties”—chunks of supplement will squish between the frames. Dump the mixed supplement into oiled pans or trays (it will stiffen overnight), then dump out and cut in the field with a spade or piano wire.

2. Make sure that you place the patty in contact with the cluster, near brood—otherwise the bees won’t touch it. Uneaten substitute can harden like concrete or become food for wax moth or small hive beetle!

3. Generally, you will want to feed stimulatory light syrup along with pollen supplement to encourage brood buildup. Indeed, if there is no nectar flow and honey reserves are short, the bees will sometimes just suck the sugar out of the patty and discard the flour! As Doolittle pointed out in 1905, colonies without ample stores are loathe to rear brood beyond (what they perceive as) their means.

4. Be aware that syrup feeding will also encourage flight and foraging behavior. Such flight during cold weather before almond pollination can be a problem. I find that a strong wintering colony with plenty of honey stores utilizes pollen supplement well without additional syrup.

5. Don’t disturb the bees in cold weather unless you have to! Colonies opened in cold weather are prone toward nosema outbreaks.

6. Many beekeepers “dry feed” powdered soy flour or yeast in the yard. This method doesn’t get as much feed into the hives, but it takes less labor (on the beekeeper’s part). It works best if the powder is placed in a partially-enclosed box or bucket, protected from rain and dew. The bees stir it up into the air, and it gloms onto their bodies electrostatically. Break the crust daily.

Timing and economics

Joe Traynor, who goaded me into writing this article, forwarded me a stack of research from 20 -30 years ago by a pair of Australians: Drs. Graham Kleinschmidt and G. Kondos. They had measured protein levels in bees’ bodies throughout the year, and compared it to broodrearing, honeyflows, and pollen flows. When I coupled their research with the new information on vitellogenin, it was a real eye opener. Finally, we could make sense of pollen feeding, and understand when it would be of greatest benefit to the colony!

Australian Doug Somerville, in his great book Fat Bees, Skinny Bees says: “The most important piece of equipment a commercial beekeeper can own is a calculator….There are two ways of increasing the profit margin, either by increasing income or decreasing expenses. Supplementary feeding strategies offer both options.”

So how do we plan a strategy? First, by understanding exactly why you’re feeding. I’m guessing that everyone understands syrup feeding, so we’re just talking now about feeding protein supplement. Feeding protein is only cost effective if colony vitellogenin levels are low, and you anticipate a benefit by raising them. That benefit might be:

1. To build up colony populations for pollination contracts, splitting, or shaking bees.

2. Prior to a honeyflow, to ensure maximum production. Kleinschmidt found that “on a good honey flow, colonies of 50,000 bees can produce twice as much as colonies of 35,000.”

3. To ensure that the generation of “winter” bees has their vitellogenin reserves topped off. This is critically important in dry summer areas and years, especially if you’re thinking of pollinating almonds in February.

4. To help prevent disease, and to minimize damage from varroa.

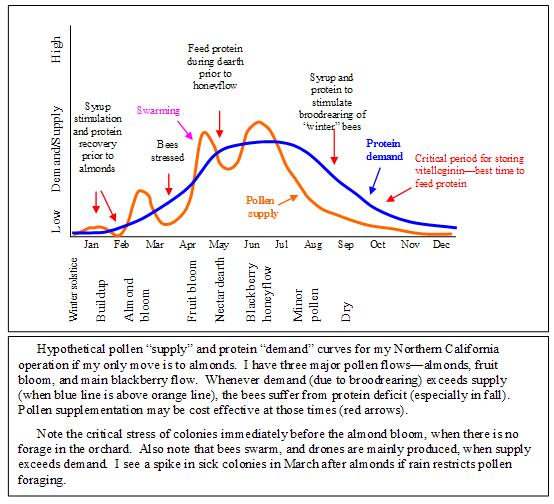

I created a graph to help you visualize when protein feeding might be worthwhile. I used my own operation as an example, assuming that I didn’t move my bees out of state for late summer pasture. Vitellogenin levels are determined by a “supply and demand” balance. I used a blue line to indicate demand due to broodrearing, and an orange line to show pollen supply. Whenever protein demand is greater than pollen supply (the blue line is above the orange line), the bees are forced to dip into their reserves. They will first eat up any pollen stored in the combs (this may take only a few days if there’s a lot of brood), then they start dipping into the vitellogenin stored in their bodies.

An important point that Kleinschmidt stressed is that the lower the bees vitelloginin titer drops, the longer it takes the colony to recover. Imagine the time lag for a starving steer to recover his body fat and musculature. Just as a rancher will put out feed for his cattle when the pastures go dry, beekeepers can give their colonies a shot of protein when broodrearing demands outstrip available pollen supplies. Kleinschmidt also pointed out that bees can suffer from protein deficit even if natural pollen is available, if the honeyflow is intense, or if available pollen does not have the right balance of amino acids. Examples of poor pollens would be eucalyptus, dandelion, alfalfa, sunflower, or blueberry.

The utilization of a graph such as this is a novel concept for most beekeepers, including myself. I don’t know of anyone who has fed at all the indicated stress points. However, at one time or another, I have fed at most points on the curve, and the results weren’t always what I expected. They finally make sense to me now! The deeper the dip of the orange line below the blue line, the more benefit you can expect from feeding.

Note in the graph the stress event the first week in February. There is often no forage available in the orchards, and some beekeepers are desperately feeding syrup to get the bees to brood up. But the bees likely don’t have much vitellogenin reserves left at that point, and the added demand of feeding additional brood exhausts whatever’s left. When those poor, depleted overwintered nurse bees then graduate to being foragers when the bloom begins, they’ve already given their all, and they just drop like flies. “Jeez, these colonies were full of bees just before bloom” is a common complaint. As one California beekeeper told me, “feeding weak colonies just before bloom in an attempt to boost strength is a waste, but it may help them to recover their health before bloom.” It also is a great indicator of queenless colonies—they ignore the patty.

Another thing to note is that there is again often no forage immediately after almond bloom. The colonies, now full of brood, burn through their stored almond pollen in a few days. Again, their vitellogenin levels plummet. Kleinschmidt found that colonies full of brood, when put on a strong honeyflow, also suffer a drop in body protein. Food for thought if you’re moving your bees from almonds to a strong citrus honeyflow.

Then we’ve got that long, dry Western summer. Mite levels peaking, lots of robbing. If there’s ever a time that bees could use some protein, this is it! Time to practice good bee husbandry. Charlie Stevens of Australia says: “Your bees are what you feed them, feed them well and they will feed you well.” Well, my bees feed me with almond pollination money, so I’m going to feed them well to make sure that they’re in top condition come February 10th!

Northern California beekeepers base their protein feeding largely upon research done back in 1984 by Dr. Christine Peng, et al. at U.C. Davis. She measured the economic return from shook package bees in May, compared to the costs of various twice-monthly feeding strategies from October through May. Peng’s study indicates that fall (Oct-Jan) feeding was more cost effective than spring feeding, and surprisingly, feeding 1/3 lb of supplement twice a month was more cost effective than feeding 1 lb each time, based upon number of adult bees in May. Concurrent syrup feeding was less cost effective. Colonies fed pollen in fall were more than twice as strong as unfed colonies come May. Populations in February also reflected the advantage of fall feeding.

The cost-benefit analysis of Peng’s study was based on 1984 prices, when we were getting, if I recall correctly, about $15 for almond pollination. With today’s pollination fees being nearly ten times higher, we may wish to revisit the economic analysis. My question is, how much supplement is most cost effective to feed currently? I’ve spoken with several commercial beekeepers, and their pollen supplement bills can be astronomical! The key issue is in grading, and how much more you’ll be paid for an eight-frame colony, compared to say, a four framer. This is currently a big issue in almond pollination, and leading bee brokers have set the bar for this year by offering premium prices for premium bees.

Premium bees can come straight from areas where there are natural fall pollen flows, provided that they have plenty of honey stores, and mites are under control. Unfortunately, in the West and South, those conditions may not exist as global warming shifts weather patterns, and droughts become more common. So we return to the concept of “feedlot” beekeeping. In this respect, we’ve got a ways to go to catch up with the rest of agriculture. If, for instance, you were going to raise laying hens, you’d start feeding the chicks with 22% protein chick starter, then switch to 17% chick grower, and finally feed them a 16% laying ration. You’d know in advance the day you start making a profit, and the day you’d need to slaughter the hens before you start to lose money. We’re a far cry from that kind of exactitude in beekeeping! Most feeding is done by guess and by golly.

The graph above can help you decide the most cost effective times to feed. The question remains, then, of the amount to feed. Hard to answer. But I look at it this way. A good colony, rearing brood, will bring in at least half a pound of pollen a day. That’s 3½ pounds a week. So I figure that’s probably a reasonable starting figure. I also know from experience that a moderately strong colony will easily consume three pounds of supplement in a week or so. Be aware that when you feed the first patty to stressed bees, you may not see the colony immediately respond–they may need that protein just to replenish their vitellogenin reserves! It may take two or three feedings for them to recover and really get back into broodrearing full swing. So if you’re in an area with a negligible fall pollen flow, three or four feedings of 3 lbs of supplement at 10-day intervals may well be a reasonable figure. I’m eager to hear the results of Dr. Frank Eischen’s recent feeding trials, which may help to answer the quantity question.

Since there’s no easy off-the-shelf vitellogenin test, it’s going to be up to you to guesstimate what shape your bees are in. If colonies are rearing drones in September, you know vitellogenin levels are high, and feeding would be a waste of money. On the other hand, if it’s the end of August, everything is scorched dry due to drought, and broodrearing has been curtailed, pollen feeding may mean the difference between dinks and boomers come February.

Now let’s talk almond pollination. Bees are renting at about $15 – $30 per frame! So what’s the return on investment in a pound of supplement? It largely depends upon when the supplement is fed, and how strong a colony it’s fed to. If you’re feeding weak colonies, you’d better start early—say August. Let’s look at costs. I mix up my own supplement from Brewtech yeast that I get from Pat Heitkam, pollen from one of the major suppliers (test it yourself—some is far more attractive to the bees), granulated sugar, and a little vegetable oil. Costs me 50¢ a pound. Thin sugar syrup about $1.35/ gallon. Three pounds of supplement and a gallon of syrup costs less than $3.00. Three feedings in August, 10 days apart, costs less than $10 total (I’ll let you figure labor, but we feed really fast). That amount of feeding will turn a small colony in my outyards into a strong colony going into almonds. I’m the world’s worst businessman, so I’m not going to offer you economic advice–I’ll let you do your own math.

I’ve got a good buddy (who is a very good businessman and profitable beekeeper) who runs a couple thousand colonies sitting on the Valley floor. He keeps ‘em close to home, and hauls feed to them in a big way. Puts on six pounds at a time sometimes. Squeezes it between each box of triples. His feeling is, if you’re going to pay for the labor of opening up a hive, why waste your time by only giving them a token amount of feed? Gives each colony up to 18 pounds in the fall. His bees are busting out of the boxes all winter, and he splits them in January with Hawaiian queens! Others feed their strongest colonies come Christmas. Pollen supplement only, no syrup. The bees eat up through the super of honey stores and turn it into brood. The beekeeper then steals brood and bees from those colonies to boost his dinks in February.

My buddy points out that you’ve already got a lot of fixed costs invested in each hive of bees. Those costs are the same whether that colony rents out, or not. The relatively small added cost of feeding protein can make the difference between profitability and loss. He can’t understand why some beekeepers are so loathe to invest in the feeding of their bees! However, the market is shifting to a demand for stronger colonies in almonds, and beekeepers who want to play the almond game may be forced to rethink their management.

It may be time for the beekeeping industry to shift its paradigm from managing boxes to really thinking about good husbandry of the critters inside. Think of each box as having a living animal inside. Don’t be afraid to invest in their nutrition, either by moving them to better pasture, or by feeding them in place. Understand the role of vitellogenin in colony protein dynamics, and you can make every dollar count! I know that these two articles have been information dense (as my articles are prone to be). I apologize for that, but there’s just a lot to know. If you want a simpler business, raise chickens.

References

Somerville, Doug (2005) Fat Bees Skinny Bees, A manual on honey bee nutrition for beekeepers. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Australia. Available on the Web at https://rirdc.infoservices.com.au/items/05-054 I highly recommend this reference!

Lactic acid fermentation of pollen: http://www.fao.org/docrep/w0076e/w0076e11.htm or Sommerville (2005), p. 30.

Allen Dick’s pollen supplement webpage and spreadsheet

http://www.honeybeeworld.com/misc/pollen/default.htm

http://www.honeybeeworld.com/misc/pollen/pollenpatties.xls

Doolitte, GM (1905) A Year’s Work in an Out-Apiary republished by Wicwas Press 2005.

Herbert, Elton W, Jr., and H Shimanuki (1971-1985) These two authors published a wealth of research on pollen supplements. They are reviewed by Herbert (1992) Honey Bee Nutrition in The Hive and the Honey Bee, Dadant & Sons

Keller, I, P Fluri, A Imdorf (2005) Pollen nutrition and colony development in honey bees. Bee World 86(1): 3-10.

Kleinschmidt, G & G. Kondos (1976-1998) These authors published a series of incredible research papers on honey bee nutrition in Australia. I’m working off photocopies, but hope to make the series available.

Kleinschmidt and Kondos (1977) The effect of dietary protein on colony performance. Proc. 26th Int. Cong. Apic., Adelaide (Apimondia)

Mussen, Eric (2007) FOOD for thought. Apicultural Newsletter March/April 2007. Dr. Mussen’s newsletters are some of the best references on issues related to almond pollination. http://entomology.ucdavis.edu/faculty/mussen/news.cfm

Peng, Y-S, JM Marston, O. Kaftanoglu (1984) Effect of supplemental feeding of honeybee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) populations and the economic value of supplemental feeding for production of package-bee. J. Econ. Entomology 77(3): 632-636.