Light or Heavy Syrup For Drawing Foundation?

January 29, 2017

Light or Heavy Syrup For Drawing Foundation?

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First published in ABJ September 2016

Since I sell a large number of nucs each spring, I need to draw thousands of deep combs of foundation every year. But due to our drought in California, this this has become difficult. So I was curious as to whether bees would better draw foundation on heavy or light syrup.

Principal Investigators: Randy Oliver, assisted by Brion Dunbar

Funding source: Beekeeper donations to ScientificBeekeeping.com.

Introduction: The production of wax to build combs comes at a substantial metabolic cost to the bees. Thus they do so only when there is a glut of incoming nectar. The science isn’t completely settled, but it appears that the stimulation for comb building occurs when the mid-age nectar receivers have trouble locating empty drawn comb into which to place their loads. Such a delay (which causes them to hold the nectar in their crops for a prolonged period) apparently triggers the activation of their wax glands. The beekeeper soon sees “white wax” in the hive, indicating that the colony is ready to build fresh comb.

Beekeepers commonly feed growing colonies sugar syrup in order to encourage them to build comb—typically to “draw out” frames of foundation. The question then is whether bees will draw out more foundation if they were being fed concentrated or dilute sugar syrup. I’ve long assumed that it would be diluted syrup, since it would take up more space in the combs. But my readers know how I feel about making assumptions…

Experimental Objectives: To test whether, given the same amount of sugar, colonies would draw more foundation if that sugar were fed in a concentrated or a dilute syrup.

Experimental Design:

- Take strong double-deep colonies immediately after the main honey flow (but while a small amount of nectar was still coming in).

- Shake all the bees into the lower brood chamber and remove the upper chamber.

- Place a deep box of wax-coated plastic foundation above each single brood chamber (no queen excluder). Weigh each super at the beginning and end point.

- Feed each hive an equal amount of 77% sugar syrup (commercial sucrose/HFCS blend, either straight (“heavy syrup”), or diluted by half to 38.5% with water (“light syrup”) (Fig. 1).

- Feed the syrup via gallon chick waterers, placed in an empty super above the hive, in order to allow for unrestricted feeding. Each hive would thus be fed at each feeding either 1 gallon of heavy syrup, or 2 gallons of light syrup, but the amount of sugar (and thus out of pocket cost) fed to each hive would be equal.

- Feed the hives continuously until most of the combs are drawn, and then individually score (by eye) each comb for the degree to which it was drawn (independent of the amount of syrup stored in the combs) (Fig. 2).

Experimental Log (Abbreviated)

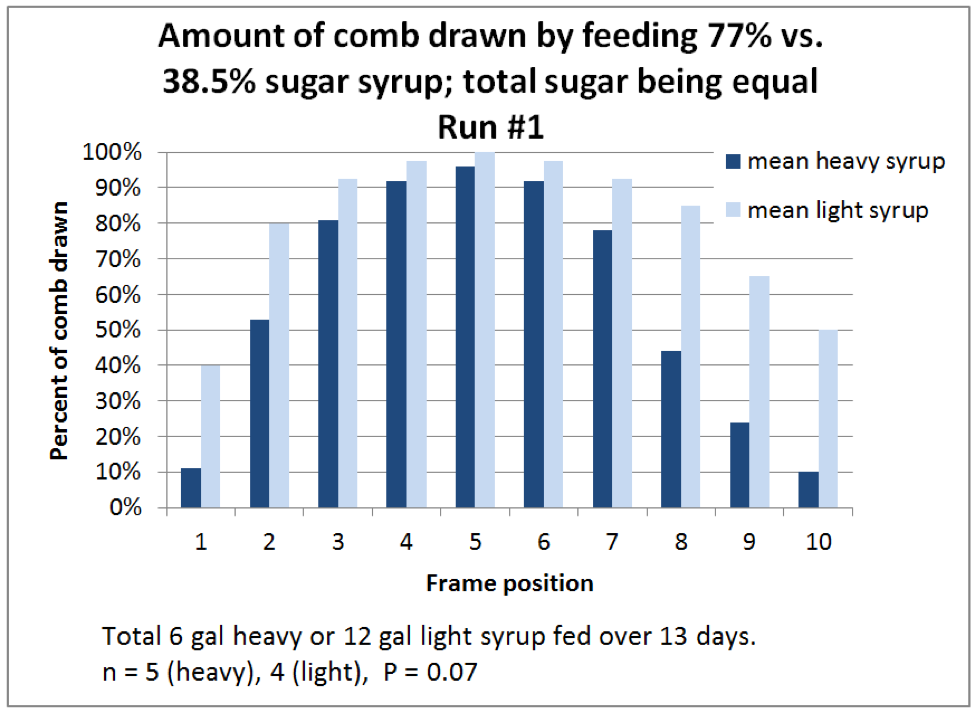

Run #1, June 17-30: light nectar flow on, other hives in yard maintaining weight. Chose 2 groups of 5 hives each. Gave 6 feedings each, for a total of 6 gallons of heavy syrup, or 12 gallons of light syrup. Was dry and hot for the first three feedings, rain and/or high humidity for the last three.

To my surprise, in both groups, the syrup from the first three feedings “disappeared” into the lower box—there was zero new wax produced until the 4th feeding. Comb drawing commenced after the 4th feeding, and then proceeded rapidly. Ended the run after 13 days, when the first boxes were nearly fully drawn. No brood was found in any super. Censored one light-syrup hive that drew an abnormally small amount of comb.

Figure 1. I’m pouring mixed sugar syrup into 1-gallon chick waterers for feeding. I scattered straw in the feeder troughs to prevent drowning and to allow unrestricted uptake of the syrup by the bees. I placed the feeders on the top bars of the box of foundation, and covered them with an empty box for protection.

Due to the slow start, I decided to replicate the experiment to see if I got the same result now that the bottom boxes were plugged out with sugar syrup.

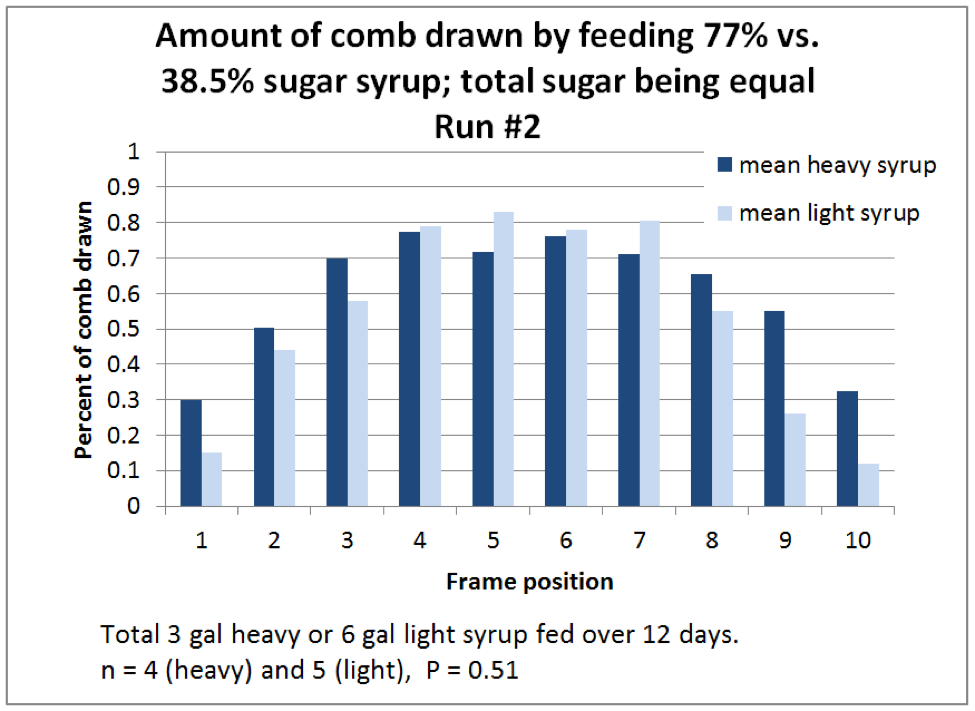

Run #2 July 6-15: Removed the drawn boxes and replaced with fresh boxes of foundation. Reversed the treatments for each group (the light syrup group now got heavy syrup), censoring the same hive as in the first run. As expected, comb building commenced more quickly than in the first run. Needed only 3 feedings over 9 days to draw the comb (for a total of 3 gal of heavy, or 6 gal of light syrup).

The results of this run were so different from the first that I ran yet another replicate:

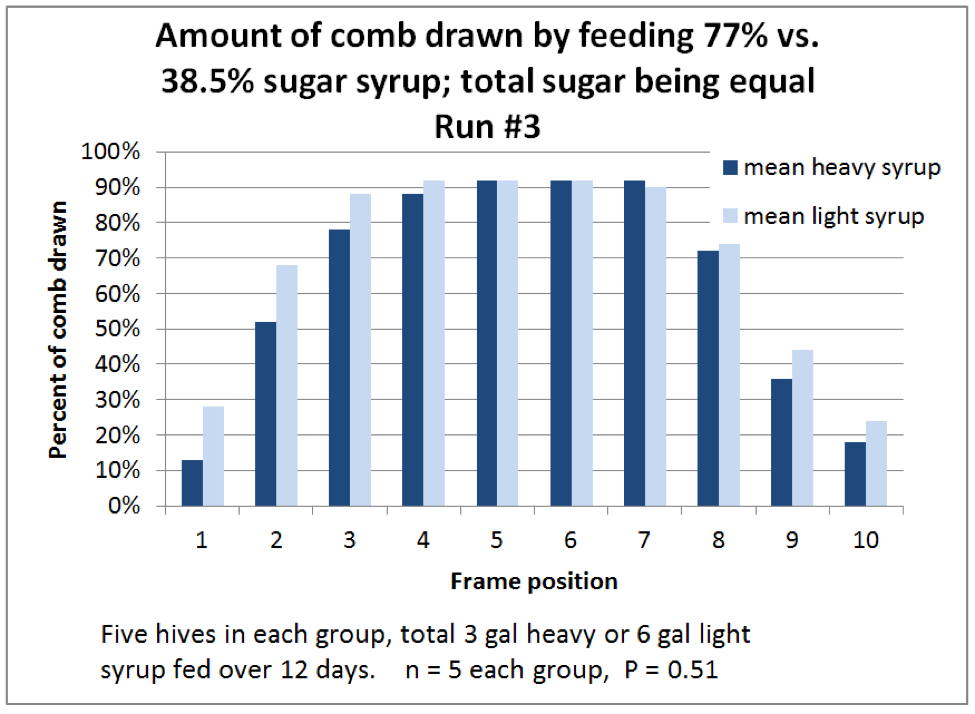

Run #3 July31-August 16: As before, removed the drawn boxes and replaced with fresh foundation, and reversed treatments. In order to cut back on feeding labor, I tried feeding from open 4-gal tubs with straw, again protected by an empty super, giving either 2 gal heavy, or 4 gal light syrup. By August 6 the syrup was not being taken well, so I poured the remaining syrup back into chick waterers as per the first two runs. A few days later I did one additional feeding, again for a total of either 3 or 6 gallons. In this run, the amount of weight gain suggested that there may have been a slight gain due to a natural honey flow.

Figure 2. It took about 3 gallons of heavy syrup to draw most of the combs to some extent. We scored each comb for the percentage to which it was fully drawn.

Results and Discussion

Run #1—no hive put brood in the second box. Calculated equivalent of fully-drawn combs: 5.8 for heavy syrup, 8.0 for light syrup (Fig. 3). Net weight gain 13.3 lbs for heavy syrup, 22.3 lbs for light syrup.

Figure 3. Not all colonies drew their combs equally from the center out, so I reordered them for better comparison. More foundation was drawn on light syrup, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Run #2—only one hive had brood in the second box. Calculated equivalent of fully-drawn combs: 6.0 for heavy syrup, 5.3 for light syrup (Fig. 4). Net weight gain 16.4 lbs for heavy syrup, 14.8 lbs for light syrup.

Figure 4. It is always important to replicate any experiment. In Run #2, at the start of the run, the brood chamber was already full of honey, so the bees immediately started drawing comb. In this run, the bees drew more combs on heavy syrup, but the difference was again not statistically significant.

Run #3—apparently due to the slower consumption, there was brood in 3 of the boxes of drawn foundation, but no apparent correlation with type of syrup. Calculated equivalent of fully-drawn combs: 6.3 for heavy syrup, 6.9 for light syrup (Fig. 5). Net weight gain 23.5 lbs for heavy syrup, 24.7 lbs for light syrup.

Figure 5. Again, no difference between syrup types.

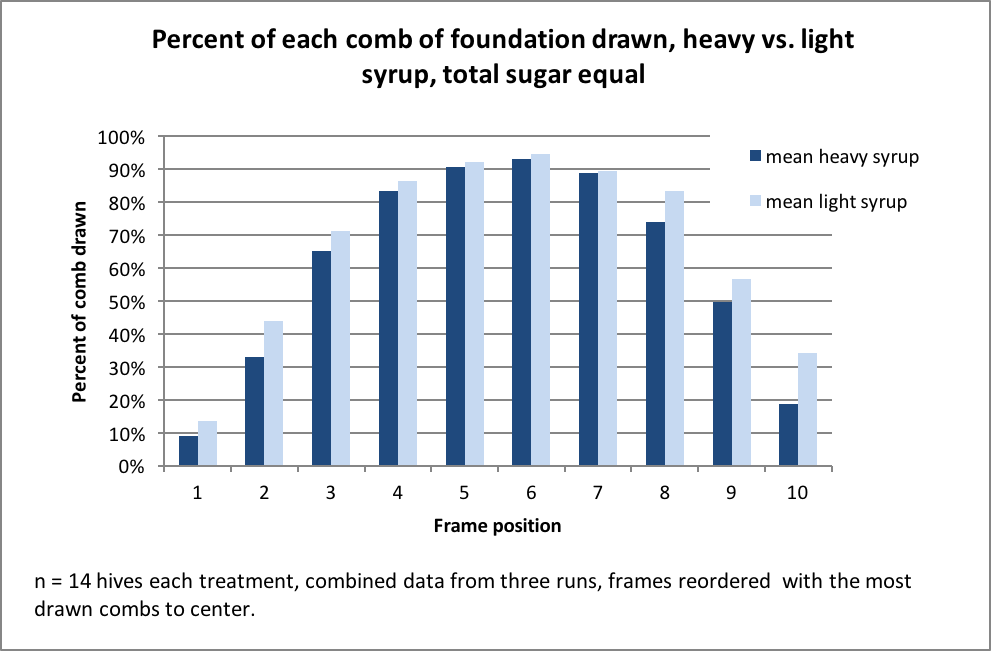

Combined results: overall, there was no significant difference in comb drawing between the two concentrations of syrup in the three replicates (Fig. 6). Nor did it seem to make much difference in the total weight gain of the supers.

Figure 6. There did not appear any substantial difference in the amount of comb drawn by feeding either heavy or light syrup. Despite the slight apparent edge for light syrup, taking labor into consideration, it would be considerably cheaper to feed heavy syrup in order to produce the same amount of drawn comb.

This result is similar to that found by Whitcomb [1], who found that colonies drew roughly the same amount of comb, regardless of the degree of dilution of the feed.

Practical applications:

- Of interest was that a gallon of heavy syrup, although fed in an easily-accessible trough with straw floats, was taken more slowly than the light syrup. The colonies consumed 2 gallons of light syrup in roughly the same amount of time as they took a single gallon of heavy syrup.

- As far as putting on stores, there did not appear to be any advantage to feeding heavy syrup over light.

- Overall, it required the feeding of the equivalent of about a half gallon of 77% syrup in order to fully draw out a single deep comb of wax-coated plastic foundation.

- Based on the results of this and my “Syrup Multiplier Effect” trials, anywhere from 55-70% of fed syrup winds up stored in the combs.

An Afterthought

It is often suggested that beekeepers should rotate out their combs on a regular basis (although many experienced beekeepers scoff at the idea). Since I sell thousands of combs in my nucs each season, I wondered just how much the cost (in honey or syrup) is for a colony to draw a comb of foundation.

The widely-cited figure is that it takes 6-8 lbs of honey to produce a pound of wax. This figure apparently comes from two studies—a very small experiment by Huber [2], published in 1814, and the previously-cited larger experiment by Whitcomb in 1946. Huber estimated that it took 5-11 lbs of sugar to produce a pound of wax; Whitcomb roughly estimated that it took 6.6-8.8 lbs of honey to produce a pound of wax. Neither study meets the degree of scientific rigor that I’d require repeat those figures without a grain of salt.

When I worked up the data from this experiment, it occurred to me that I might be able to calculate approximately how much syrup it took to draw out just the wax in a deep box of foundation, by subtracting the weight gain from the stored sugar “honey” (since the wax in the cell walls weighs only a fraction of a pound). But I did need to make some SWAG assumptions [3].

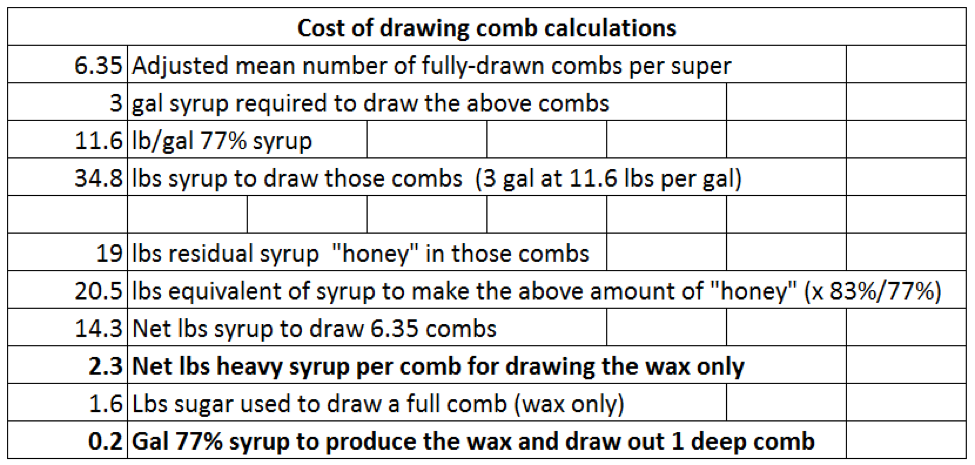

In any case, below is a snip from my Excel spreadsheet (Fig. 7):

Figure 7. The percentages drawn of the combs were added up to arrive at the adjusted number (e.g., two 50% drawn combs = one 100% drawn comb). So although it took a half gallon of heavy syrup to draw a comb, after subtracting the weight of the “honey” stored, it actually took only about 2/10ths of a gallon to produce the wax and draw out a deep comb.

The above figure is remarkably close to that calculated by Whitcomb, who arrived at a figure of roughly 1.6 lbs of honey to draw a single comb [4].

Update: Szabo, who provided his test colonies with beeswax foundation rather than the wax-coated plastic foundation that I used, calculated that it took only 200-400 g of sugar, which works out to less than a tenth of a gallon of heavy syrup required to draw a comb. However, Szabo considered a comb to be “drawn” when the cell depth reached 0.5 cm, which is only about a third the depth of a fully-drawn comb. Since he used wax foundation, the amount of sugar used may have been mainly used for heat production and the mechanical work of reworking the beeswax foundation, rather that the actual production of beeswax.

Tibor I. Szabo (1977) Effect of Colony Size and Ambient Temperature on Comb Building and Sugar Consumption by Honeybees, Journal of Apicultural Research, 16(4): 174-183.

Practical application: there is a cost to rotating out combs. If you can sell your honey for $2.50/lb (a ballpark figure), then it would cost roughly $5.00 in lost honey production to draw a single comb (not to mention the cost of the frame and foundation). Perhaps a more reasoned recommendation for comb rotation is that if the brood looks healthy, then the comb is likely not contaminated, and perhaps can be of service for a while longer.

Acknowledgements

As always, my buddy Pete Borst helped immensely with research for this article. I also thank beekeeper Brion Dunbar for his assistance in grading the frames, and my sons Eric and Ian for help in feeding.

Notes and citations

[1] Whitcomb, W Jr. (1946) Feeding bees for comb production. Gleanings in Bee Culture. April 1946: 198-203,247.

[2] Huber, F (1814) New Observations Upon Bees. Translated by CP Dadant, 1926.

[3] SWAG is a technical acronym for “Scientific Wild Ass Guess.” My assumptions, since I didn’t think to weigh the brood chambers) were that their weights were steady after the first run. And since the other hives in the yard appeared to be holding their weights steady on the natural light nectar flow, I ignored the roughly ½ lb of honey that a colony consumes per day during summer. And that since the lower box was plugged out after the first run, any weight gain of the super would represent the amount of syrup converted to honey (since the weight of beeswax in freshly-drawn combs is negligible—estimated by Whitcomb at 0.188 lbs). Thus the difference in weight fed vs. weight gained would be the cost of converting fed syrup into drawn comb.

[4] His paper wasn’t clear whether he was drawing deeps or mediums, and he fed unsaleable honey rather than sugar syrup.