The How and Why of Oxalic Vaporization: Part 1

December 29, 2025

Contents

THE PROCESS OF OXALIC ACID VAPORIZATION 2

THE PHYSICS AND CHEMISTRY OF OXALIC ACID VAPORIZATION 3

THERMAL DECOMPOSITION OF OXALIC ACID 6

WHAT GOES IN, DOESN’T COME OUT! 6

HOW TO CAPTURE THE VAPOR OUTPUT FOR ANALYSIS? 9

QUANTIFICATION OF THE ACIDIC OUTPUT VIA TITRATION 15

BUYER BEWARE: THE NEED FOR STANDARIZED TESTING 16

The How and Why of Oxalic Vaporization

Part 1

First Published in ABJ October 2025

Randy Oliver and János Fenyősy

ScientificBeekeeping.com

Oxalic acid can be applied to a colony by a number of different methods — vaporization being one of them. But by vaporization, how much of the dose that you put into the device actually comes out of the vaporizer?

There’s a huge change taking place in our industry as varroa finally evolves resistance to amitraz, leading many beekeepers to start shifting to organic acids and thymol for mite control. This has created a market for new registered formulated products and application devices. Many beekeepers just want to know “what works.” But it’s not that simple. So I’m writing this series of articles for those who want to understand how and why oxalic vaporization works (or doesn’t).

I have extensive experience in my own hives with applying oxalic acid (OA) by the dribble or extended-release methods, but since the vaporization method (OAV) has also become popular in some areas, I’ve done a bit of experimentation with it also.

The main advantage of vaporization is that you don’t need to crack open the hive (no lifting involved, and it can be performed in cold weather). It’s also assumed to result in a more even distribution on the bees [[1]], and application can be relatively quick (with some of the “guns,” nearly as fast as the dribble or laying in extended-release pads). The main downside of OAV (other than risk of inhaling the vapor) are that when a colony contains brood, it exhibits low efficacy [[2]].

There are now dozens of different brands of vaporizers on the market (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 You have a wide variety of choices for how to apply oxalic vapor to hives — every one claiming that theirs is the best. It’s easy to make claims, but what we beekeepers need are hard data as to how well they actually perform.

To answer that question, let’s first look at the process involved in the vaporization of oxalic acid.

THE PROCESS OF OXALIC ACID VAPORIZATION

All vaporizers (as opposed to foggers) fall into two main categories — the first being the “pan type,” such as the Varrox (invented in Germany by Markus Bärmann & Thomas Radetzki and patented in the year 2000 [[3]]. This style of vaporizer works well, but application takes some time. When you put a gram of oxalic acid granules into a cold Varrox, it slowly melts as the temperature rises, boils, then vaporizes into a cloud of white microcrystals. The entire process takes 2 ½ minutes to heat and vaporize, followed by another 2 minutes cooling with the power off. Five minutes per hive works for a recreational beekeeper, but not for large operations.

THE PHYSICS AND CHEMISTRY OF OXALIC ACID VAPORIZATION

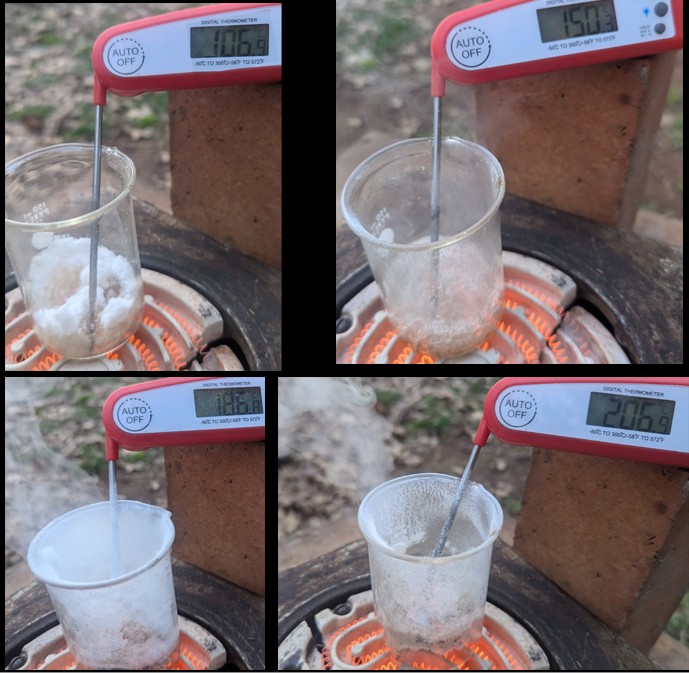

In a pan-type vaporizer, the oxalic acid dihydrate does not initially vaporize as it’s heated, but rather first melts and dissociates from its water of crystallization, forming a supersaturated aqueous solution of oxalic acid. This can be viewed by heating OA in a beaker (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 I started cold, and turned on the heating coils. As the bottom of the beaker warmed, the OA dihydrate crystals initially melted into a clear liquid. At around 110°C (230°F) the water of crystallization begins to boil out and continues to do so up to around 135°C (275°F), at which point some acid begins to recrystallize on the inner sides of the beaker above. By 185°C (365°F) serious vaporization of OA begins to take place, and most of the acid is gone from the bottom by 215°C (419°F). It’s not clear whether the acid actually sublimates (direct solid to vapor) or simply boils off.

Practical application: You can see why a pan-type vaporizer cannot have sides — the acid would recrystallize inside the chamber, separated from the heating element. This can also be a problem in any vaporizer set to low temperature.

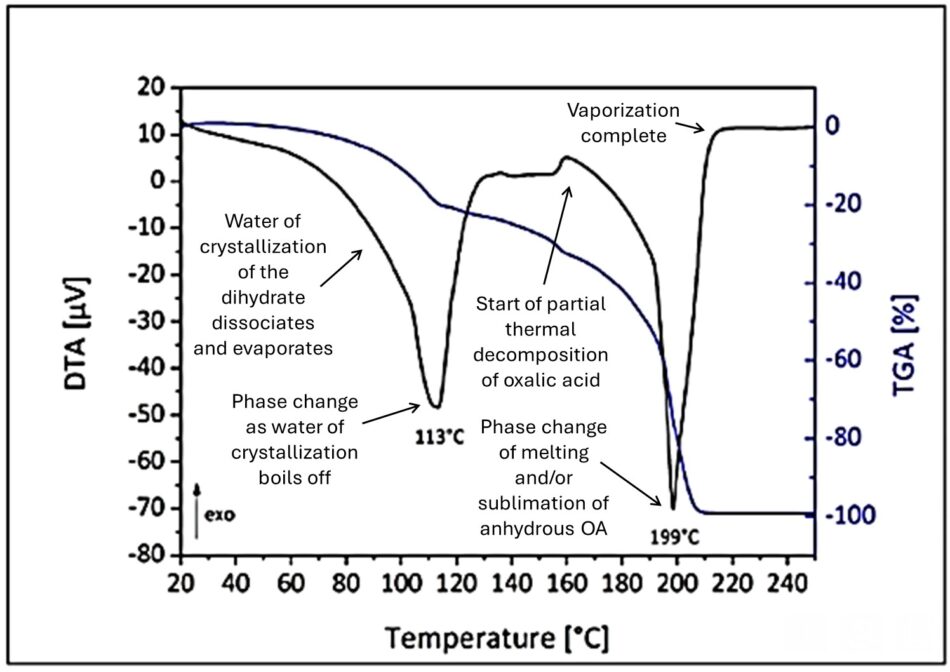

My coauthor János obtained an informative thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) [[1]] chart of the progression from Professor Barna Kovács of Hungary (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 A thermographic analysis measures the rates of temperature increase (DTA), and weight loss (TGA) as a substance is slowly heated. The dips in the DTA show how the heating rate slows (relative to that of an inert control), first due to the phase changes of oxalic acid dihydrate as is dissociates into water (initially from a solid into a liquid solution of water and anhydrous oxalic acid, and then as the water of crystallization boils off). Then there’s a second dip as it undergoes a phase change as it vaporizes into vaporous oxalic acid or its decomposition products. My thanks to Professor Kovács.

Side note: Oxalic acid dihydrate, due to its high latent heat (the heat energy needed to change its phase state from solid to liquid) is being considered for thermal energy storage as a phase change material [[4]].

Practical application: From 190-210°C, it likely takes less energy to decompose OA than to vaporize it. The key question then is, how much acid degradation takes place during the process? As we’ll see, this is largely a function of the start-point temperature of the vaporizer.

GUN-TYPE VAPORIZERS

Faster than the pan-type vaporizers are the “gun” type (Figure 4), which have the huge time advantage of requiring no cooling cycle and can be loaded while still hot.

Fig. 4 A thermal camera side view shot of a vaporizer in action. Notice how quickly the temperature of the vapor output drops as it exits the vaporizer. The exiting steam and oxalic vapor are invisible until they cool and condense into the white fog that we observe (which occurs within the first inch of exhaust).

These oxalic guns are mostly powered by electricity (AC, automobile batteries, or now lithium-ion rechargeable batteries), but some by propane. Time is money, so large-scale beekeepers are looking for the most rapid application methods. In response, some manufacturers are promoting guns that can vaporize oxalic very quickly.

Our concern: Oxalic acid can chemically degrade at high temperature. So turning up the heat for rapid vaporization may create a problem — especially when beekeepers are vaporizing larger doses of OA. One gram of OA can be vaporized quickly, but 8 grams can take a while. This raises a question: Will raising the vaporization chamber setpoint temperature (for 10-second vaporizations) result in excessive degradation of the oxalic before it enters the hive?

THERMAL DECOMPOSITION OF OXALIC ACID

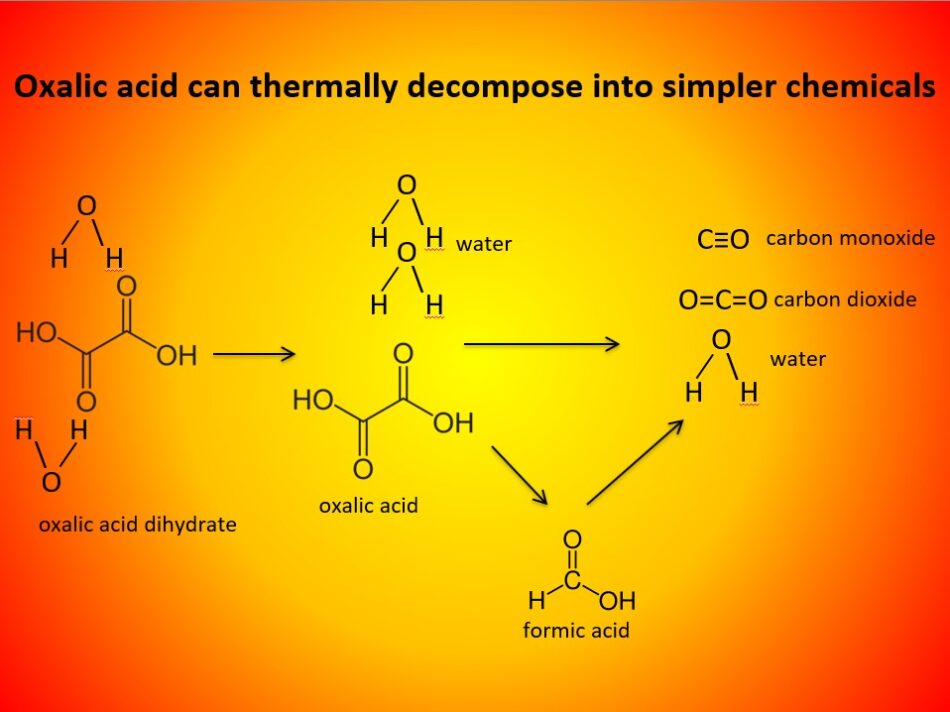

The vaporization of oxalic acid is not a “clean” process. Dependent upon the temperature, and time duration of the heating cycle, it can also decompose into simpler chemicals (Figure 5).

Fig. 5 Most all beekeepers have read Wikipedia’s quote that “Oxalic acid vapor decomposes at 125-175°C (257-347°F) to CO2 and formic acid (HCOOH). If that were true, we’d easily smell the formic vapors, and no oxalic acid would make it into our hives. The reality is that yes, it does decompose to some extent (but not until at least 185°C).

WHAT GOES IN, DOESN’T COME OUT!

Way back in 2018, OxaVap sent me a vaporizer for testing. Since I had heard concerns that some of the OA might break down at the device’s 230°C (446°F) setpoint temperature, and since many beekeepers were asking whether it degraded into formic acid (and whether formic went into the hive), I ran some experiments (Figures 6 & 7).

Fig. 6 We’ve all seen the huge cloud of OA fog that comes out of a vaporizer — enough to easily fill a double deep. But what happens if you shoot it into a cool balloon?

Fig. 7 In order to determine whether the inputted OA degraded during heating, I shot the vaporizer’s output of into a mylar balloon in order to capture it. To my astonishment, the cloud of vapor recondensed immediately upon entering the balloon, and there was no inflation — except for a little bit between 190 and 210C (you gotta see it to believe it!). What happens is that the oxalic and water vapors immediately cool and recondense back into oxalic acid dihydrate (plus a bit of decomposition gas for a few seconds). I could then rinse out the balloon with distilled water and titrate the rinsate to quantify how much acid remained.

Practical initial findings: I found that as little as half the amount of OA placed into the vaporizer ever made it into the balloon (or would wind up in a hive). I also detected no odor of formic acid in the balloon.

The above was not in any way a criticism of the ProVap, but an issue for any vaporizer. This bugged me for several years, and then last year I was inspired to further investigate by János Fenyősy from Hungary (the developer of the InstantVap vaporizer), who asked me to corroborate his findings on OA degradation and optimal setpoint temperature. János greatly impressed me for having gone into meticulous detail in designing and testing his vaporizers, so this spurred me to follow up with additional tedious titrations of my own to see whether my independent results would corroborate his findings. This led to a great collaboration, so I asked him to coauthor this article so that we could share our important findings with beekeepers worldwide.

Practical application: The questions then are:

- To what extent does OA decompose in a vaporizer?

- What are the decomposition products?

- How does the setpoint temperature affect decomposition?

- How hot is too hot? (Or too cold?)

- And finally, what is the optimal setpoint temperature?

HOW TO CAPTURE THE VAPOR OUTPUT FOR ANALYSIS?

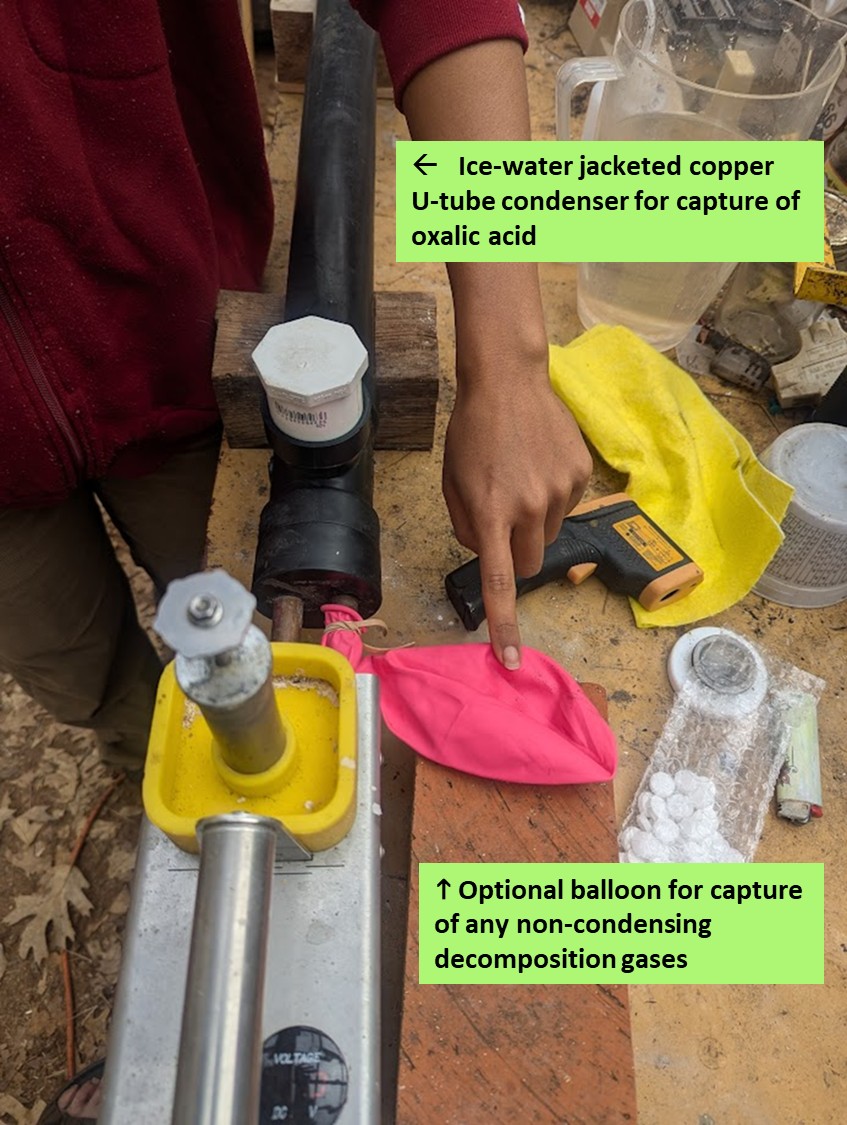

János and I worked independently to collect our data, and self-fabricated similar, but different apparatuses and methods. I found that mylar balloon fill ports had changed since 2018, so experimented with a wide variety of capture apparatuses. I finally settled on a U-tube of 1/2“copper pipe encased in a jacket of ice water, with the option of attaching a rubber ballon to the exhaust end to capture any exiting gases (Figures 8 & 9).

Fig. 8 We performed our vaporization tests outdoors, with different types of vaporizers shooting their exhaust stream through a stopper with a tight hole [[5]].

Fig. 9 Most all of the oxalic output condensed within the first few inches. Afterwards, we would take the device to the lab and thoroughly rinse the inside of the copper pipe with three 125 mL washes of pH-adjusted distilled water analyte solution.

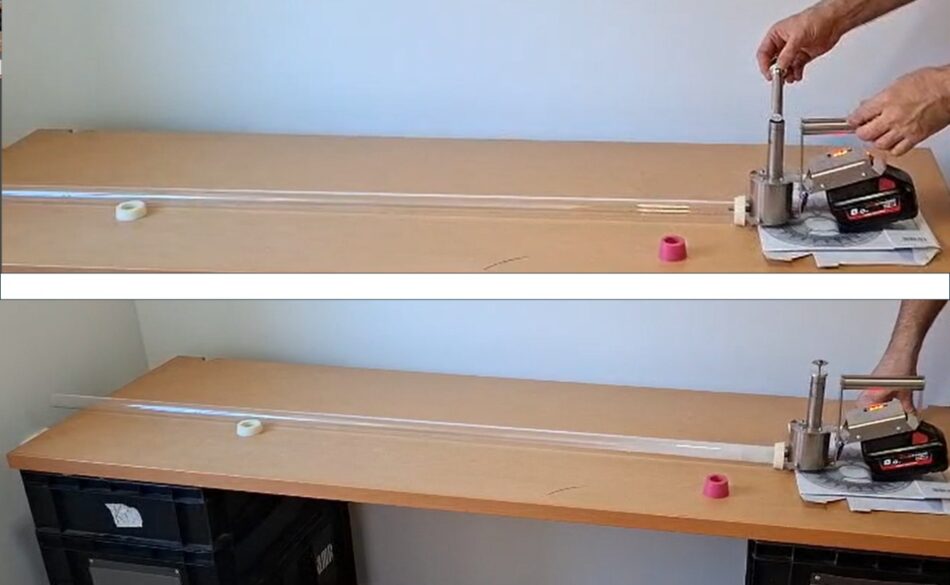

János also tested different apparatuses for capture, and wound up using a glass tube to capture the vapors (Figures 10 & 11).

Fig. 10 János’ apparatus was simpler, using a glass tube, so that he could observe the condensation and recrystallization processes.

Fig. 11 Recrystallized OA dihydrate in one of János’ glass tubes. To compare our results, we both used data only for the amount of acidity in the capture tubes.

I unsuccessfully tried to measure the temperature inside a vaporizer myself, but found that there was no good method (Figure 12).

Fig. 12 Neither infrared nor probe thermometers worked for this purpose (note the different temperatures on the thermometers). So I had to depend upon each device’s built-in thermistor, which may or may not reflect the temperature to which the oxalic is actually exposed.

And then there are the degradation products. I had already determined by smell that formic acid wasn’t normally produced, but wondered what gas was being produced. I determined that formic vapor was not flammable, so held a lighter under the exiting gas, and found that it ignited a blue flame — only between 190 and 210°C (Figure 13). Aha! It appears that the main decomposition produced is carbon monoxide.

Fig. 13 The acid-free gas that escapes the condensation tube ignites only between 190 and 210°C, just as most of the oxalic acid is undergoing vaporization.

QUANTIFICATION OF THE ACIDIC OUTPUT VIA TITRATION

So how much acid actually comes out of a vaporizer, relative to what you put in? János and I used slightly different methods of acid-base titration, so I’ll explain just mine. Once we’ve rinsed out our condensation tubes, using distilled water tinted with phenolphthalein indicator dye (pH pre-adjusted to slight pink), we titrated with a calibrated NaOH solution drop-by-drop from a burette until we reached the “endpoint” at which the indicator dye reverted back to its starting color (Figure 14).

Fig. 14 By dripping in a carefully calibrated solution of sodium hydroxide titrant (which neutralizes any acid), we can watch for a color change in the indicator dye in the analyte rinsate from the condensation tube. From the amount of titrant needed, we can then calculate how much acid (free hydronium ions) there was in the rinsate, and then convert that figure to “oxalic acid equivalents.” You can watch a video of the process at [[6]].

Notes: For any chemically-inclined readers, yes, later on we’ll determine how much of that acidity was due to the presence of formic acid. These dozens of titrations are tedious, but very informative, and I appreciate the assistance of my helpers Rose and Corrine.

As we do titrations, I can’t help but humming a tune (apologies to the Beach Boys):

I’m pickin’ up good titrations.

They’re giving me excitation.

Good, good, good, good titrations!

We can easily and accurately titrate down to a twentieth of a gram oxalic acid equivalent, and generally run a few replicates of any dose at each temperature setting. Next month we’ll show you what we’ve found.

BUYER BEWARE: THE NEED FOR STANDARDIZED TESTING

In order to pitch their products, some vaporizer manufacturers are making extravagant (and unverified) claims that their vaporizer designs are efficient, cause less degradation of the oxalic acid, or can apply rapid-fire (or multiple-hive) treatments. János as a manufacturer, and I as a beekeeper, agree that our industry needs a standardized testing procedure to validate these claims, so that beekeepers can make informed decisions when evaluating which devices suit their needs.

NOTES AND CITATIONS

[1] I’ll provide data on this later on.

[2] More on this in prep.

[3] EP1294225A1, and then upgraded in U.S. Patent US9992978B2 in 2016 by Michael Detrich Maher.

[4] Wang, J, et al (2019) Form-stable oxalic acid dihydrate/glycolic acid-based composite PCMs for thermal energy storage. Renewable Energy 136: 657-663.

[5] I first hand made wooden stoppers that wouldn’t melt, then used silicone stoppers, then finally realized that a copper cap with a tight hole drilled through it worked best (since it wouldn’t cool the vapor as it passed through the outlet tube going through a stopper). We of course included any residues on the stoppers in our titrations.

[6] Titration video https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/zxbnkro4gvisggir62j3v/Titration-phenolphthalein.mp4?rlkey=s9yrlqbn2vtojxctkjzm9kk4t&st=32qrmx1t&dl=0