Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance Part 3: The Equipment Required

December 29, 2025

Contents

INTRODUCTION – SOME ARTICLES FROM 2017 1

LET’S PUT TO REST TO A COMMON MISCONCEPTION 3

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MITE WASH TECHNIQUE 3

DEVELOPMENT OF A DEVICE TO DO THOUSANDS OF MITE WASHES 4

A SYSTEM TO AVOID CONFUSION IN THE FIELD 5

DEVELOPMENT OF PORTABLE IN-FIELD AGITATORS 7

Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance

Part 3: The Equipment Required

First Published in ABJ October 2025

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

Apis mellifera has again and again demonstrated its ability to evolve resistance to varroa — when the mites kill off the non-resistant colonies. On the other hand, in a selective breeding program there’s no need for any colonies to die, so long as you allow only those that did not need help to pass on their genes. All it takes is an easy method to identify those colonies.

INTRODUCTION — SOME ARTICLES FROM 2017

Looking back, I’ve been trying to get our commercial queen producers onto this bandwagon for a long time. To that end I wrote a series of articles back in 2017 and 2018.

In Mite-Resistant Bees — Pipedream or Plausible? [[1]] I wrote:

[In 2008] our industry was not yet ready for [mite-resistant stock] — some hobbyists perhaps, but not the commercial guys who have the greatest impact upon the managed bee breeding population. … As I’ve previously explained, the inevitable failure of amitraz may change that, since without an inexpensive, effective miticide at their disposal, mite control will become more difficult.

Practical application: Well, with last season’s failure of amitraz in a number of operations, that time has come. I’d also written:

I feel that the time has come to present the argument that we should finally get serious about dealing with varroa. For thirty years we’ve been managing The Varroa Problem with flyswatters and Band-Aids. We could make beekeeping so much easier if we, as an industry, worked together to shift the genetics of the North American bee population toward stocks that were able to manage varroa on their own.

And then in Bee Breeding for Dummies [[2]] I laid out how to do it, and wrote:

Over a million queen bees are sold each season by commercial producers in the U.S. Yet as far as I can tell, few are sold with the claim of being “mite resistant,” despite the fact that varroa is our number one problem.

In a recent scientific paper, Dr. John Kefuss and collaborators wrote two profound sentences with which I heartily concur: “We believe that it is the responsibility of everyone who breeds bees to try to select for mite resistance to reduce chemicals in hives. We owe this effort to the general public and to future generations of beekeepers.”

I followed with Walking the Walk [[3]]:

We beekeepers need to move beyond varroa, and turn varroa management over to our bees. Breeding for mite resistance is indisputably the long-term solution to The Varroa Problem. My half-assed breeding efforts to date have shown some success, but I’m as yet unable to dispense with mite management. It’s clearly time to step up my game.

There are others successfully keeping bees without needing mite treatments, and I want to be there too (but without going through the pain and cost of the Bond method). Perhaps by sharing my trials and tribulations in attempting to breed for mite resistance, I can further our collective progress.

And then in 2018 I detailed the relatively small cost involved in Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance: 1000 hives, 100 hours [[4]]:

What we now need is for the commercial bee breeders to all start joining in. To that end, I’ve suggested a simple and workable program for them to follow.

My plea to all commercial queen producers: Let’s stop complaining about varroa. It’s not that hard (or expensive) to up our game, and all of us to engage in realistic and workable selective breeding for, or sustainable production of, mite-resistant stock.

MY OBJECTIVE

So long as beekeepers get their queens from professional producers, our industry is going to be stuck with varroa until those producers are all offering mite-resistant bloodlines. My sons and I produce several thousand queens a year, but our season is too late to provide queens for the April market. We did a trial collaboration with Olivarez honey bees last year to produce queens for market, and this year demand by return customers went through the roof.

Practical application: In 2017 I prematurely wrote [[5]], “I strongly suspect that industry demand for mite-resistant queens is about to shift.” In 2025 I now smell a change in the wind. Beekeepers may finally start demanding mite-resistant stock. This will create new business opportunities for innovative queen producers.

My objective is to show other queen producers how to lift the burden of varroa from our shoulders. Our producers are all experienced and successful beekeepers, and many are justifiably proud of the excellent strains of bees that they’ve developed. I’m trying to show them how to go about breeding for, and maintaining, mite-resistant stock of their own.

Practical application: I’ve laid it all out — it’s there for the reading. Let me make something clear — these articles are not about promoting my own breeding stock — I want to show every queen producer how to breed for, and maintain, their own mite-resistant stock. The beauty is that one doesn’t need to be a scientist, it does not involve the loss of any colonies, and (if one is using registered miticide products) the process actually pays for itself!

LET’S PUT TO REST TO A COMMON MISCONCEPTION

I commonly hear beekeepers saying that mite-resistant bees must be spicy or non-productive. This is patently untrue — it depends entirely on your ranking of the criteria that you use for selection. I’ve invited a number of skeptical large-scale beekeepers and queen producers to inspect our mite-resistant colonies along with me. They all come away in amazement, saying, “Boy was I wrong!”

As an example, here’s a validating email that I received this July from Kansas beekeeper Gary LaGrange, the founder of a wonderful program that changes the lives of traumatized veterans by introducing them to beekeeping [[6]]:

We now have several hundred of your Golden West colonies. They are the most docile bees that I have worked with and great honey producers, far exceeding our other colonies. We are studying the mite outcome, but initial alcohol wash counts are smaller by about half from those from our other colonies.

Practical application: Focusing solely upon mite resistance may be good for proof of concept, but why bother if you wind up with a stock that is spicy or nonproductive? Prioritize the traits that you select for. Ours are (in order):

- “Gentleness” — bees that are docile and pleasant to work with (we have zero tolerance for “spicy” colonies).

- Productivity — strong spring buildup and above-average honey production (they gotta make us money).

- They control varroa by their own means, requiring no treatments to keep mites in check.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MITE WASH TECHNIQUE

My aha moment came when we first started performing large-scale mite washes. As a small-scale California queen breeder, with nothing unique about my stock, my first across-the-board mite wash of our colonies allowed me to discover Queen Zero — which told me that I already had all the genetics necessary for mite resistance already present in my stock. And that it was likely that every other queen producer may also have some resistant colonies in their operation.

The practical question then is: What is the easiest way to identify which colonies carry the genetics for resistance, without having to allow any colonies to die?

I needed to determine every colony’s degree of varroa infestation for a thousand or more hives. To do that I did a deep dive into varroa monitoring — feel free to read my findings in the articles here [[7]]:

After completing the above research, I concluded that the best assessment method was swirl-agitation mite washes, using either 90% alcohol or Dawn detergent (ether rolls or sugar shakes were not accurate enough, and sticky board counts too labor intensive).

But there was no realistic way that we could hand-agitate thousands of mite washes, so we needed some sort of mechanical agitators that we could take to the field for on-the-spot determination of each colony’s infestation rate (so that we could immediately apply treatment if necessary).

DEVELOPMENT OF A DEVICE TO DO THOUSANDS OF MITE WASHES

Via experimentation, I found that shaking or vibration didn’t do the job. Living in the Gold Country of California, I was quite familiar with the swirling hand oscillation that we used with a gold pan to precipitate flakes of gold through the gravel. It turns out that the same motion will precipitate mites from a sample of bees. So I jury-rigged an old motor to oscillate twelve mite-wash cups at a time (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 My first mite-wash agitator, based upon the principle of circular oscillation (with an experimentally determined offset, and adjustable frequency). This agitator had a 120V motor, and required a voltage inverter to run off a truck battery, but it could be confusing to keep track of which cups had received a standardized oscillation duration.

A SYSTEM TO AVOID CONFUSION IN THE FIELD

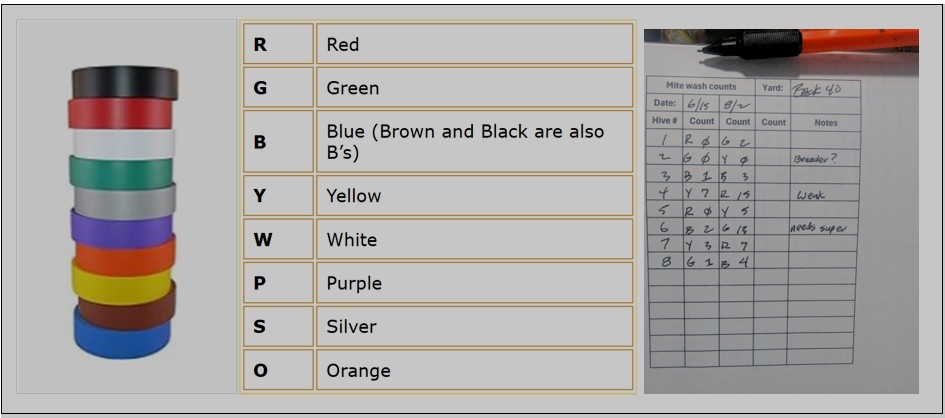

One needs to link each wash cup to the hive that its bee sample was taken from. Since we had up to six people working together in the field at the same time (with unnumbered hives, and some of us taking the bee samples, and others manning the agitators), we developed (via a great amount of trial and error) a “foolproof” system for keeping track of which bee sample came from which hive. We found that using colors (rather than words, letters, or numbers) to match each sample to the hive worked best (Figures 2-4).

Fig. 2 Color-code your cups with inexpensive vinyl tape. On the field data sheet, mark the letter for the color of the cup when you record the wash count. This gives you a checkback if there is any question. If your hives are numbered, simply write down the color of each sample cup when you place them on the hives.

Fig. 3 We use color-labeled cups and matching hive markers to identify the hive each sample came from. We wrap the tape with the bottom at the optimal liquid fill level (2¾”). This is all the equipment needed for sampling — an 18-qt dishwashing tub, a half-cup measuring cup, wash cups and wooden markers.

Fig. 4 Here are Tara and Rachel back in 2017 at their station on a truck bed, setting up cups and matching hive markers to distribute to the hives, while the rest of us took bee samples from the hives.

DEVELOPMENT OF PORTABLE IN-FIELD AGITATORS

A multi-cup oscillator works well for batches of cups brought back to a home base for processing, but was confusing to standardize the duration of agitation for each sample. What we really needed were battery-powered agitators (with built-in timers) that could be used in the field right on top of a hive or flatbed, so that we could immediately tag each hive with its mite count and apply a treatment if necessary.

Over the years, I’ve designed, built, and tested dozens of prototypes of different designs of portable agitators (Figures 5-10), using 12-volt motors so that their batteries could be recharged directly from a truck cigarette-lighter socket.

Fig. 5 My first designs used an oscillating ring to hold the cup. These worked well, but were difficult to build and adjust, and required lubrication.

Fig. 6 We like having individual agitators, rather than those that hold multiple cups, plus you’re not stuck if there is a problem with one. This allowed Brooke to process multiple samples simultaneously (I tried double-cup agitators, but didn’t like them).

Fig. 7 To allow our technicians (in this case Sandy) to work in the shade, slightly away from all the bee activity, I built a pull-out table in the back of my Honda CRV for a dedicated mite-wash vehicle.

Fig. 8 In later prototypes I tried different types of cups and holders, alternative drives, and added magnifying mirrors for viewing and counting the mites.

A big breakthrough was when I figured out how to dispense with stapling screens to the bottoms of the inner wash cups. In last month’s ABJ I showed my inexpensive new cup design, now being sold by my helper Jacob (Jake) McBride. [[8]] (I’ll soon publish instructions on how to make them yourself).

Fig. 9 Jake and I developed this current generation of portable agitators, which come with a built-in magnifying cup holder, and an adjustable timer. We’ve designed these so that any handy beekeeper (anywhere in the world) could build one in their home shop with off-the-shelf parts. I’ll be publishing the plans, but for now, Jake is building and selling them to queen producers worldwide [[9]].

Fig. 10 There’s also a speed controller so that you can adjust the critical swirling agitation to match the fill level and number of bees in the sample — a huge improvement.

This field agitator design is the result of years of field testing, performing tens of thousands of mite washes. A crew of three of us recently took mite-wash counts from 170 hives in 150 minutes — that’s less than 3 man-minutes per wash count. I’ve updated how to perform “Smokin’-Hot Mite Washin’ — 2025 update” at [[10]].

Those beekeepers who have actually performed mite washes on every colony for the first time, invariably tell me that it’s like being unblinded. Even with identical management and treatments, the hive-to-hive variation in mite infestation rates from yard to yard (or in any yard) can be huge. With the right equipment, it’s a heckuva lot cheaper to get a wash count from every hive, than to waste money on unnecessary treatments, or to suffer the loss of colonies that needed extra attention.

Practical application: At $20 per hour for labor, that works out to $1.00 per mite wash. With almond pollination rents in the $200 range, there’s no excuse for a commercial operation to be losing half their hives due to inadequate varroa monitoring! A queen breeder can determine the infestation rates of a thousand hives for around $1000 in labor, which will likely be paid for by the savings from foregoing unnecessary mite treatments, and avoiding the loss of colonies to varroa.

NEXT MONTH

I’m not about to tell you what to do, but I’ll show how we are successfully breeding for mite resistance.

CITATIONS AND NOTES

[1] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/mite-resistant-bees-pipe-dream-or-plausible/#_ednref4 (January 2017 ABJ)

[2] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/the-varroa-problem-part-6a-bee-breeding-for-dummies/ (March 2017 ABJ)

[3] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/the-varroa-problem-part-7-walking-the-walk/ (May 2017 ABJ)

[4] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/selective-breeding-for-mite-resistance-1000-hives-100-hours/ (March 2018 ABJ)

[5] Bee Breeding for Dummies, op cit.

[6] https://www.valorhoney.org/our-story

[7] All the articles below are at ScientificBeekeeping.com.

Re-Evaluating Varroa Monitoring: Part 1 – Methods.

Part 2- Questions on Sampling Hives for Varroa.

Part 3- How Does Mite Distribution Vary Frame-to-Frame in a Hive?

Part 4- What About Letting the Shook Bees Fly Off?

Refining the Mite Wash: Part 1- Treatment Threshold and Solutions to Use.

Part 2 – Mite Release.

Part 3- Dislodgment, Precipitation and Separation.

Part 4 – Comparing the Release Agents.

[8] You can order them at forbeessake@gmail.com. $20 + shipping for a 10-pack (to pass out at your local club).

[9] Same email as above, $350 + shipping (cheaper than you could build one yourself).

[10] Smokin’-Hot Mite Washin’ https://scientificbeekeeping.com/smokin-hot-mite-washin-2025-update/