First published in: American Bee Journal, July 2015

Understanding Colony Buildup and Decline – Part 6

Hiccups in Colony Linear Buildup

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ in July 2015

CONTENTS

Return To Playing Catch Up

Real World Hiccups

The Effect Of Cold Weather

The Effect Of Rainy Weather

Spring Starvation

From Too Little To Too Much

Brood Survivorship

Adult Survivorship

Take Home Message

Acknowledgements

Citations and Footnotes

Under ideal conditions, colonies grow in a linear manner once the broodnest is well established. But ideal conditions don’t always occur in the real world. By being aware of factors that may reduce the rate of colony buildup, the beekeeper may be able to intervene and get the colony back on track.

Return To Playing Catch Up

Creating a mathematical model for colony buildup and decline is not a mere academic exercise–it has great practical application. When you attempt to create a mathematical model, you quickly find out which critical elements you don’t fully understand.

Practical application: in my own case, my newfound understanding of exactly why weak colonies are able to catch up in size with stronger colonies helps me to better grasp why springtime splits have the potential to grow as large as established colonies. Ideally, I want to split my colonies small enough to keep them from swarming, but large enough that they can build to optimal honey-producing strength.

But when I was faced with my sons’ questions as to what is the ideal amount of brood and adult bees to put into each split, I realized that I couldn’t honestly answer with certainty. So I spent considerable time in creating a spreadsheet to calculate the growth of nucs dependent upon those variables (as well as temperature and quality of the queen). I’m currently testing that model by carefully tracking the individual buildup of nucs in a test group specifically created with different measured amounts of brood and bees. I’ll let you know when I get the results.

Real World Hiccups

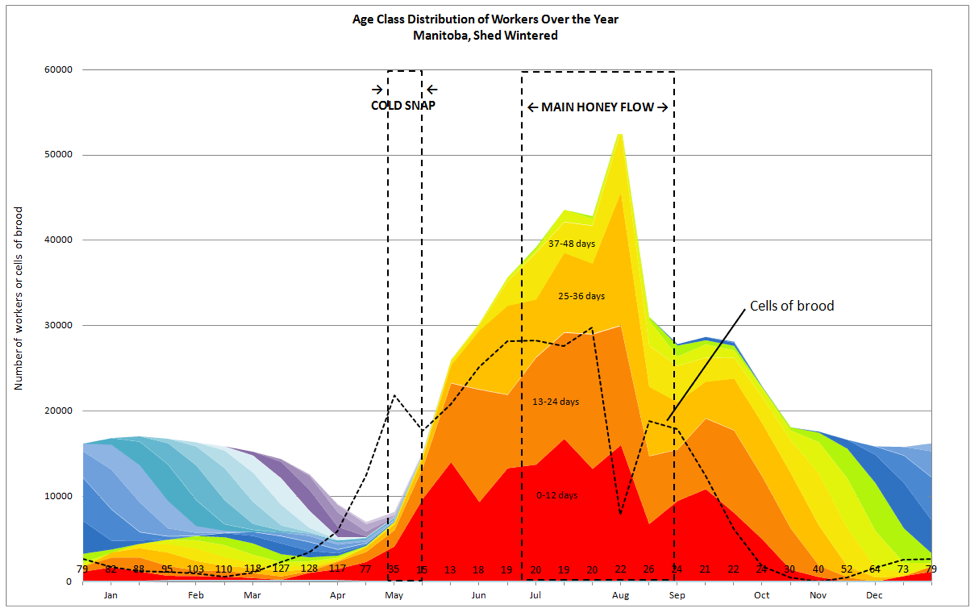

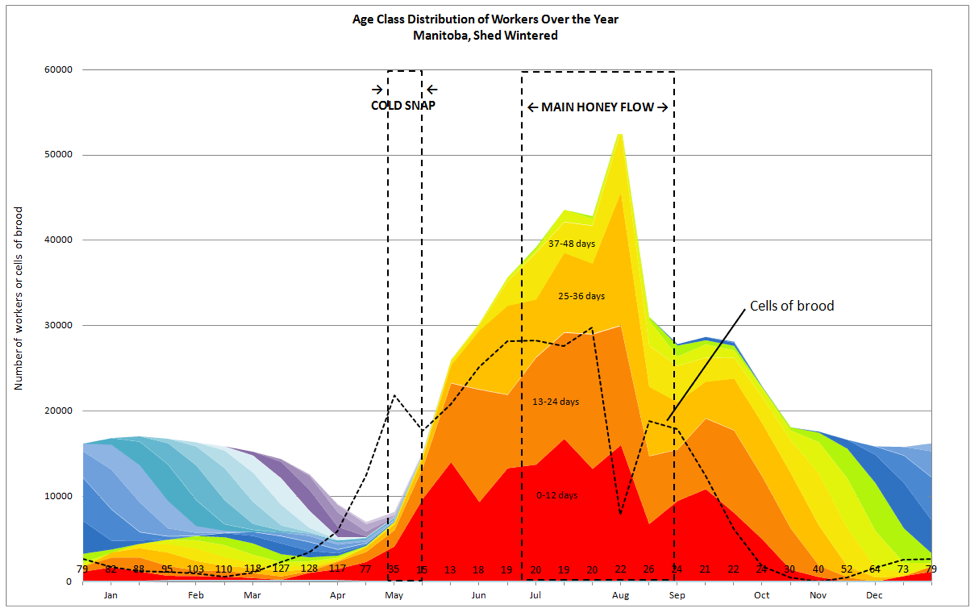

I find the modeling of colony growth under ideal conditions to be mathematically elegant. But of course in the real world, conditions are often less than ideal. Any number of transient phenomena can handicap colony growth, or thwart it altogether. So let’s take another look at the hiccups in growth exhibited by Harris’ colonies in my colorful chart of colony demographics (Fig. 1):

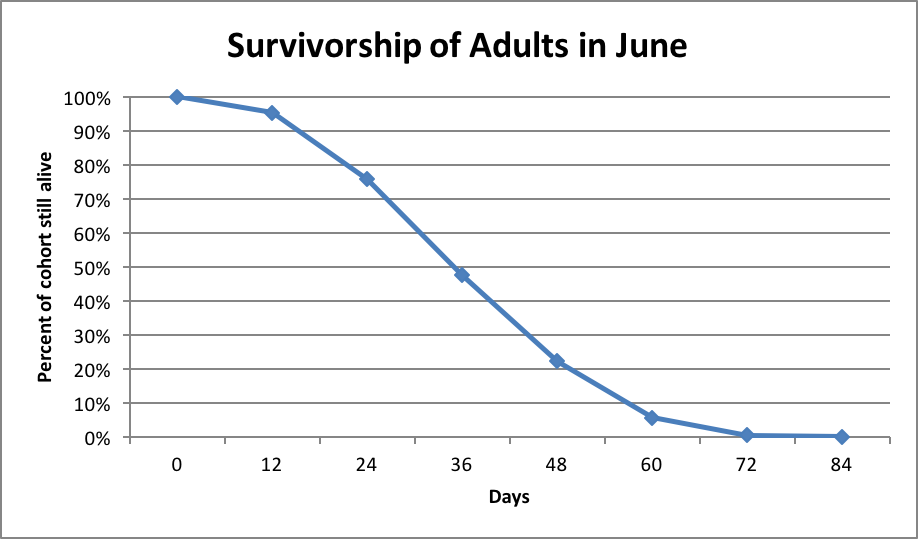

Figure 1. Note the three instances (in mid May, early and late July) in which broodrearing was curtailed, leading to hiccups in the expected linear growth of the colonies [[i]]. I’ve indicated on this graph the timing of a spring cold snap, as well as the main honeyflow.

[i] These hiccups in egglaying are broken out by individual queen in Fig. 1 of my previous article

So what caused those sudden reductions in egglaying?

The Effect Of Cold Weather

I searched the weather history for Manitoba during the period of time during which Harris collected his data. It appears that the first dip in egglaying occurred during a cold snap in early May, right during the critical “spring turnover.” The cold weather would have precluded foraging for pollen, and the freezing nighttime temperatures (15°F) would have forced the tiny clusters (averaging only about 7000 adult bees—less than 4 frame’s worth) to contract tightly—thus limiting the amount of comb suitable for broodrearing.

Practical application: cold nighttime temperatures are a major limiting factor for the buildup of small colonies, since they must go into tight cluster, which severely limits both the size of the broodnest, as well as the number of bees available for nursing duties (since the majority must be engaged in forming a heat-generating “insulating shell”).

The Effect Of Rainy Weather

April showers may bring May flowers, but even a single day of rainy weather may have a profound effect upon a growing colony. In a meticulous and intriguing study from the lab of Austrian bee researcher Karl Crailsheim [2], a rain machine was used to prevent the bees in an observation hive from foraging for only a single day at time, while keeping the inside temperature constant. What they found was that:

During rainy periods nurses spent less than half as much time nursing brood as they did during sunny periods. Our experiment suggests that the activity of the nurses is linked to the influx of food and its passage from bee to bee. Nurses receive food more often and over a longer period on days with good weather conditions than on days with bad weather conditions… It seems that the flow of nectar diminishes after only one night and causes the decline in nursing activity even on the first day with bad weather conditions and the following night.

Wow, even a single day of rain cuts nursing visits to brood by half! The researches didn’t make observations on what happened during longer storms, but I have. After about three days of rainy weather, a rapidly-growing colony will have completely depleted its pollen stores, and begins to go into protein deficit, forcing the nurses to start using their body reserves (in their fat bodies). And then it may get worse…

During prolonged rainy weather, a colony may shift from rapid growth to cannibalism of the brood within a matter of days. Such an unexpected disaster hit us hard a few years ago. In the photo below, we were adding second brood chambers to strong singles on a nice nectar and pollen flow in mid May, right at the beginning of our main honey flow (Figs. 2-5).

Figure 2. In mid May 2011, our colonies were rapidly building during our spring flow, and we had recently added the second brood chambers for them to move into, with the expectation that they’d be quickly filled with brood and honey. This was beekeeping at its best!

Figure 3. We were running an experiment at the time, and I happened to take a photo of a typical brood frame. Note the reserves of honey and beebread present on May 10th. A few days later the colonies were shaking nectar and whitening wax.

Figure 4. We live in the mountains, where the weather is rapidly changeable. We got hit by a surprise snowstorm on April 25. All photos were taken in the same yard.

Figure 5. Within four days, the hungry colonies had consumed all honey reserves and all pollen reserves. They then desperately started cannibalizing the brood–first the eggs, then young larvae, then older larvae. They don’t normally cannibalize sealed brood, since it no longer needs to be fed, and those pupae may be the colony’s only chance for survival.

We donned our cold weather gear and madly fed syrup. We were able to avert major brood cannibalism in most of our colonies, which quickly recovered when the weather turned back to warm. But those colonies that were forced to cannibalize their brood got set back so hard that they were unable to even put on winter stores during the main flow, and needed to be fed later in the season.

Practical application: someone incredulously asked me, do you really go out and feed bees during miserable weather? I answered, Well, duh, ‘cuz during good weather they’re able to feed themselves–that’s why we are called bee keepers.

Such brood cannibalism [3], albeit less dramatic, frequently occurs in my area during the two week pollen and nectar dearth that we typically experience between the end of apple bloom and the beginning of the late spring flow. I often observe plenty of freshly-laid eggs each day, but the nurses apparently eat them up rather than trying to feed larvae when there is not enough protein coming in.

Practical application: the main determinant of the development of a busting colony for honey production is having a steady supply of pollen and nectar coming in during the period beginning 6-8 weeks before the start of the main flow. It is during this time that the feeding of pollen sub can be of great benefit during periods of inclement weather or pollen dearth (as occurs in my area immediately after the end of fruit bloom).

Spring Starvation

In my area, other than during storms or the two-week post fruit bloom dearth, there is usually plenty of nectar and pollen coming in during springtime, and we rarely need to feed our splits. But from time to time, we must perform emergency feeding of the ravenous growing colonies. In the case of the colonies in the experiment shown in the photos above, I could not get approval to break protocol and feed the hives during the storm (despite my daily entreaties). The result was that a number starved on the fourth night (Figs. 6 & 7).

Figure 6. It breaks my heart to see a vigorous young colony starve to death, as indicated by the heads buried in the cells.

Fig. 7. After 4 days of bad weather, many of the colonies in the experimental yard succumbed to starvation. It was heartbreaking and ugly–this is a view of a typical bottom board. This disaster could have been easily averted by the feeding of a few dollars worth of sugar in any form.

I’ve also seen similar starvation of my strongest colonies during almond bloom if the weather turns foul. Many’s the time that I’ve dumped granulated sugar over the combs (if I didn’t have syrup with me) in order to save a colony. One time, all it took was a can of soda pop poured over the immobile bees to give them enough energy to move onto some swapped frames of honey.

During intermittent nectar dearths, colonies lacking adequate honey reserves can suffer minor starvation events. Unless you are closely monitoring the yards, all that you may see is a handful of dead bees in front of the hive, and if there has been a resumption of the nectar flow since the brief dearth, you may not be able to figure out what caused the kill (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. A “minor” starvation event occurred in this outyard in late June during a brief break in nectar availability. No colonies died, but similar to this one, most had a small pile of dead bees in front (this occurred in an area far from any pesticide applications). Only by checking the age structure of the remaining brood was I able to figure out what had gone wrong, since by the time I took this photo the colonies had replenished their nectar stores.

Practical application: during these recent drought years in California, we can no longer count on our normal nectar flows. This spring has been scary—our colonies have repeatedly been on the edge of starvation, since we kept expecting the “normal” nectar flows to kick in. As I type these words, I’m starting to resign myself to the possibility that the main flow is simply not gonna happen, and that I am going to be forced to spend a fortune on sugar in order to keep my colonies alive.

It’s clear that a shortage of nectar/pollen (even due to a few days of rain) can bring recruitment to a temporary halt; conversely, a surfeit can also do the same…

From Too Little To Too Much

A nice nectar and pollen flow is extremely stimulating to broodrearing. But on the other hand, too much nectar or pollen can result in the bees plugging the broodnest, filling comb that the queen would normally fill with eggs (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. A brood comb following favorable weather in almond bloom. The past few years we’ve had great foraging weather during almond bloom, sometimes resulting in the broodnests getting plugged out with pollen and nectar. Since the queen can’t find a place in which to lay eggs, there will little recruitment of emerging workers three weeks later, and colony populations may temporarily dwindle, much to the dismay of those beekeepers needing to shake packages or make splits.

Practical application: during spring buildup, it may be necessary to either reverse the brood chambers, or to add drawn comb to the broodnest to give the queen additional room in which to lay.

Tip for beginners: excessive feeding of syrup to colonies can also cause plugging out of the broodnest, leading to swarming in the spring, or poor wintering in the fall (due to lack of broodrearing at the end of the season).

Brood Survivorship

Keep in mind that colony buildup is all about the difference between the rates of recruitment of new workers and the rate of attrition of older workers. Pathogens that affect the brood reduce the rate of recruitment. When I began beekeeping, AFB was the only brood disease that we worried about—chalkbrood had yet to reach our shores, and EFB would go away on its own once a good nectar flow resumed. Nowadays, I rarely see AFB. What I do see in spring is persistent EFB (Fig. 10), and sometimes other unidentifiable brood diseases [4].

Figure 10. European Foulbrood can bring colony buildup to a screeching halt by decreasing the rate of larval survival. The larvae in this photo are clearly symptomatic, but in many cases are difficult to detect. Unlike the EFB of yore, today’s EFB may not clear up without treatment.

Although I don’t see much chalkbrood any more, a few years ago I visited apiaries on the East Coast in which chalkbrood was running rampant, preventing colonies from building up. And it is not just pathogen-caused brood disease that may cause a problem. Toxic pollen (such as that of California Buckeye), nutritionally inadequate pollen, smokestack pollution, chilling of the brood due to anything that causes high adult mortality (virus, nosema, pesticides), or pesticide/miticide residues can all affect the colony similarly, in that they may reduce larval survivability.

Practical application: any factor that reduces larval survivability (such as chilling, poor nutrition, toxins, or disease) will decrease the rate of recruitment, and have a profound effect upon not only the rate of colony buildup, but unless the problem is resolved, also upon its ultimate population size.

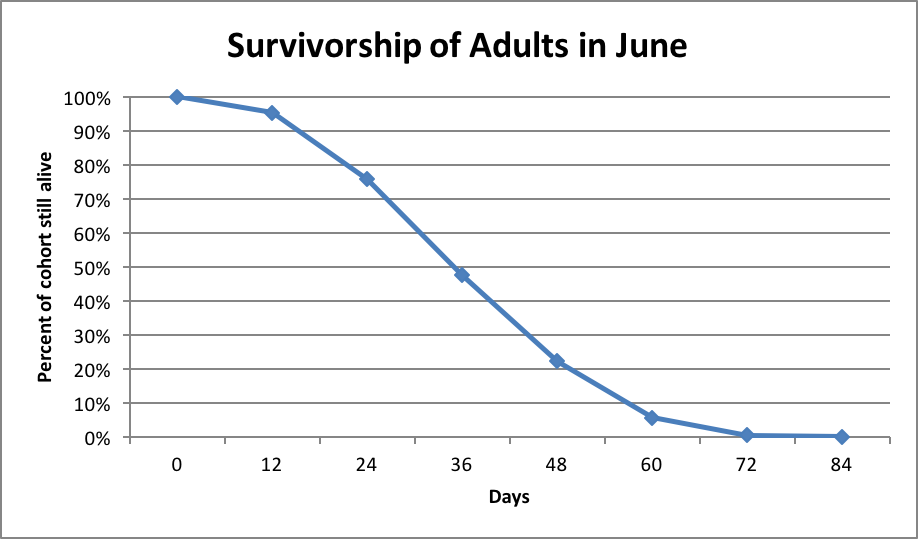

Adult Survivorship

The rate of colony buildup is also determined by the rate of attrition of the adult bees. Ideally, springtime workers can be expected to live for an average of about 35 days. During spring buildup, adult survivorship is critical to colony success. I find that infection by either viruses or nosema can prevent a successful spring turnover due to their decreasing adult survivorship [5].

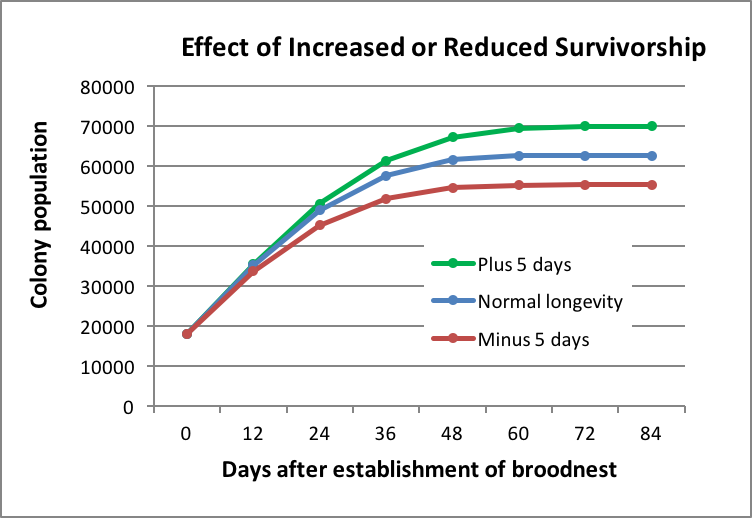

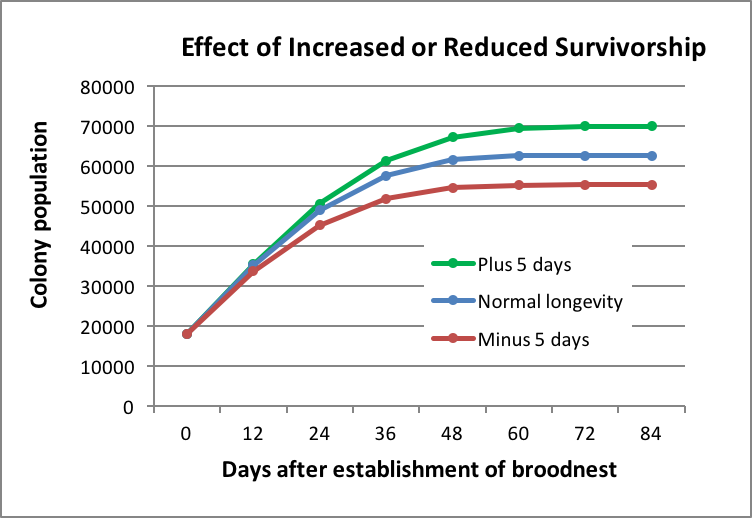

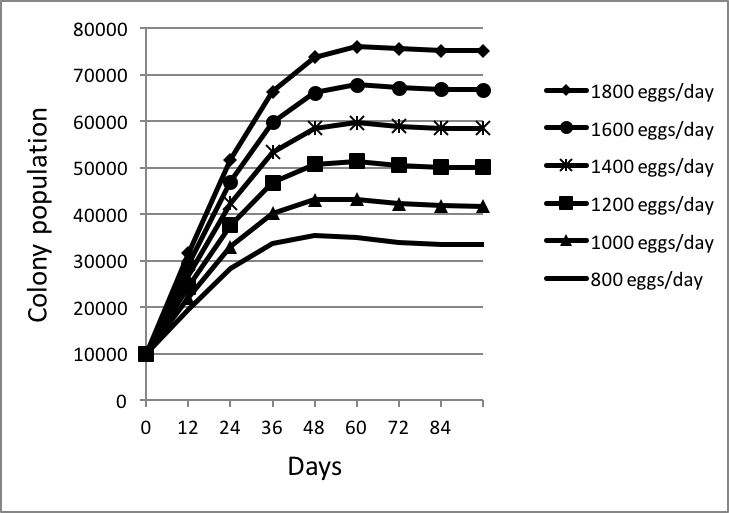

It doesn’t take much of a reduction in adult survivorship to exhibit a profound effect (Fig. 11):

Figure 11. In order to create this graph, I shifted Harris’ survivorship curves either longer or shorter by 5 days (roughly a 14% increase or decrease in average survivorship). Note how even a few days increase or reduction in average worker longevity has a profound effect upon colony buildup and eventual maximum population.

Practical application: any factor that negatively affects either larval or adult worker survivorship can make a huge difference in eventual colony size and honey production.

Take Home Message

Once a broodnest is established and the population has grown to the extent that the queen can hit her stride in egglaying (which takes a cluster covering at least 7 frames), the honey bee colony has the potential to grow at a linear rate of increase of nearly 2 frames of bees per week. But things don’t always go well for growing colonies. As beekeepers, we can provide husbandry to minimize any breaks in the momentum of colony buildup, as well put by Jeffrey in 1959 [6]:

…in Britain colonies are ordinarily increasing in size for only about three months out of the twelve, and in late summer and throughout the long autumn, winter and early spring, numbers are steadily declining This would apparently point to two important principles in commercially successful bee-keeping: first, that the bee-keeper ought to guard carefully against any break in that swift and steady upward surge in the number of bees during April, May and June—for a break at this time cannot be fully retrieved later—and in particular it is suggested that queenless intervals should be most carefully avoided; and secondly, steps should be taken to reduce to a minimum the rate of decline during those other nine long months.

Next month: I’ll continue with the swarming impulse

Acknowledgements

As always, my thanks to Lloyd Harris and Peter Borst.

Citations and Footnotes

[1] These hiccups in egglaying are broken out by individual queen in Fig. 1 of my previous article

[2] Riessberger U, & K Crailsheim (1887) Short-term effect of different weather conditions upon the behaviour of forager and nurse honey bees (Apis mellifera carnica Pollmann). Apidologie 28: 411–426. Open access.

[3] Schmickl T & K Crailsheim (2001) Cannibalism and early capping: strategy of honeybee colonies in times of experimental pollen shortages. J Comp Physiol A 187(7):541–547.

[4] For symptoms of some of the “new” brood diseases, see https://scientificbeekeeping.com/sick-bees-part-18a-colony-collaspse-revisited/

[5] See Figure 11 in Part 3 of this series.

[6] Jeffree, EP (1959) Op cit.

See also Jeffree, EP (1955) Observations on the growth and decline of honey bee colonies. Journal of Economic Entomology. 48: 732-726.

First published in: American Bee Journal, June 2015

Understanding Colony Buildup and Decline – Part 5

Egglaying, Adult Survivorship, and Modeling Colony Growth

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

First Published in ABJ in June 2015

CONTENTS

Some Questions Begging For Answers

Survivorship Of The Workers

A Simplified Mathematical Model

Question: Why Does The Population Stop Growing After 10 Weeks?

Population Top Out

Playing Catch Up

Next

Acknowledgements

Citations and Footnotes

I could wax poetic about the wonder of the honey bee superorganism, but when it comes to making management decisions, it is more informative to use a reductionist approach to understand why to do what. In the case of colony buildup, this means studying the math of recruitment vs. attrition. So let’s do the math!

I left off during the linear growth phase of the colony (following the spring turnover) with several unanswered questions:

Some Questions Begging For Answers

- To what extent does a queen’s pace of egglaying vary over the course of a season?

- Why does it seem to take only 6-10 weeks to reach maximum colony population?

- What determines the maximum size to which a colony will grow?

- Why can weak colonies sometimes catch up with those that got a head start?

- And why does the population stop growing after 10 weeks?

So let’s see if we can find answers to each of these questions in turn:

Question: To what extent does a queen’s pace of egglaying vary over the course of a season?

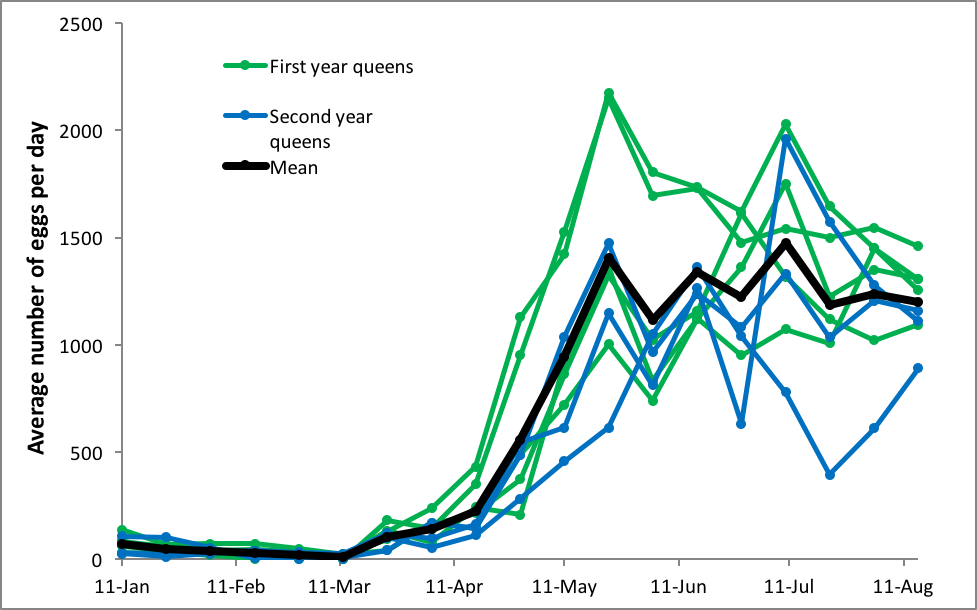

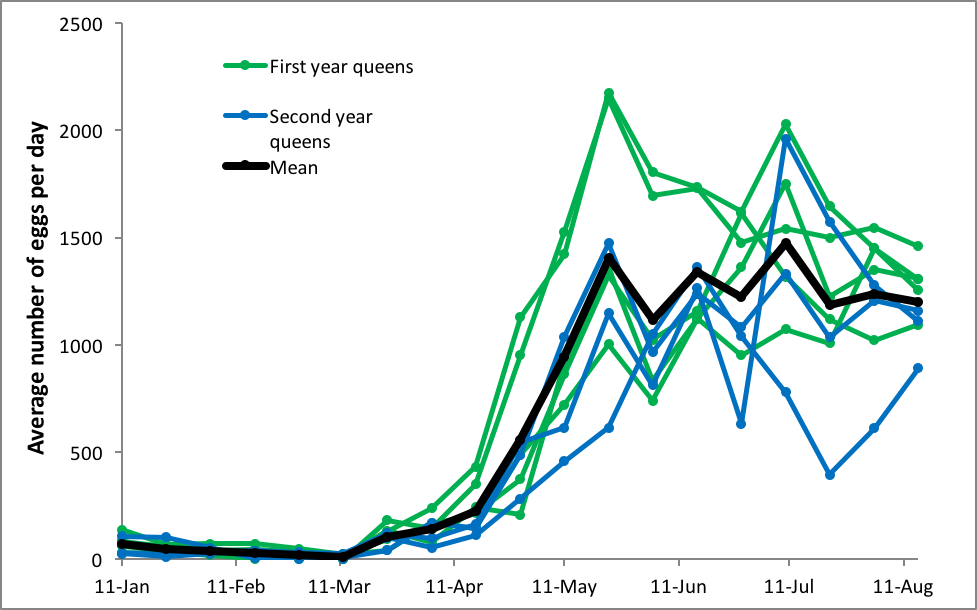

In order to answer this question, we’d need regular measurements of the amount of sealed brood in a number of colonies over the course of the season. And again, Lloyd Harris’ data provides us with that information. I plotted out his measurements for established colonies in their second year, five of which had been requeened the previous July, and three of which had queens in their second year (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Average rates of egglaying [[i]] for 8 different queens in overwintered colonies over each 12-day time period in the spring of 1977 in Manitoba. In these two groups of hives, the queens tended to rapidly ramp up their egglaying as the colonies expanded their broodnests in April and May, tending to peak in mid May, and then settle back down a bit afterward.

[i] Specifically, the amount of sealed brood, which underestimates the actual rate of egglaying.

In answer to our question, Harris’ queens hit peak egglaying early in the season (young queens exhibiting the higher rates), and then tended to level off at a lower rate (although still at nearly an egg a minute, 24 hrs a day). The hiccups in brood production appeared to be related to crowding of the broodnests during nectar flows (and then bursts of egglaying as the cells were cleared). The swarm impulse didn’t occur until July.

Practical application: as far as management for maximum egg production, there are four main things that the beekeeper can do: (1) protect the hive from cold, (2) keep young queens, (3) manage the broodnests to avoid restriction of the queen’s ability to find a place to lay (this could involve reversing the supers, or rearranging or adding drawn comb), and (4) feeding during times of dearth or poor weather.

Scientific Notes:

Scientists typically present the results of their studies as mean (average) values for each test group, but means alone may mean little. When you look at graphs showing means (averages), be sure to look at the error bars (usually the standard error of the mean—SEM) which is an indication of how much variation there was relative to the size of the group. If the error bars are large relative to the differences in means between the test groups, then the reader may want to ask what was the cause of that variability.

The human brain is far better at detecting patterns in pictures rather than in columns of numbers. For this reason, my readers may notice that I tend to favor showing raw data in graphical form for each individual colony, in order to let you use their own eyes to see the degree of variation from colony to colony, yet at the same time to look for patterns or trends.

Another frequently misunderstood term is “significance,” which the lay reader may confuse with meaning “substantial” or “meaningful.” This is often not the case. A scientist can’t say that there was any difference between the results from two test groups unless it was “significantly different” from that which would be expected to occur due to random variation—this is called statistical significance. But statistical significance may not have much practical application.

As a hypothetical example, imagine a study in which a researcher treated 1000 hives with a test substance (also running 1000 control hives). Imagine that the result was that the test substance appeared to increase mean honey production in the test group by 1 ounce per hive. Due to the large “n” (number of hives), that result might allow the researcher to state that “feeding the product significantly increased honey production.” But few beekeepers would get too excited about a product that increased per-hive productivity by only an ounce—in this case the results might be significant statistically, but insignificant practically.

On another subject, in this series I’m drawing heavily upon Lloyd Harris’ exemplary data set. But one must be cautious about extrapolating general principles based upon a single data set. Keeping this in mind, I’ve compared Harris’ data to that of many others, both historical and recent, and feel that it is indeed representative.

Now that we have good estimates for the range of rates of egglaying, we can calculate the total recruitment of new workers over any period of time. For example, simple math shows that at the rate of say 1200 eggs per day, a colony’s total recruitment over 6 – 10 weeks will result in an additional 60,400 – 84,000 workers. But from this we must then subtract the attrition of aged or worn out workers. In order to calculate this, we must understand the expected survivorship of those workers.

Survivorship Of The Workers

As recently pointed out by my friend Peter Borst [2], beekeepers have long speculated about how long a worker honey bee lives, but it wasn’t until the advent of good marking paints that this question began to be answered with hard data.

Worker survivorship is well reviewed by Woyke [3], who found that:

- Workers’ lives appear to be shortened by the amount of broodrearing that they do.

- An intense honey flow can also shorten their lives.

- Measured mean worker lifespans (by various researchers) varied from 16.6 to 37.6 days, perhaps averaging (during the productive season) about 30 days.

- Woyke also noted that despite high brood production, under unfavorable conditions colonies may not reach populations exceeding 30,000 bees.

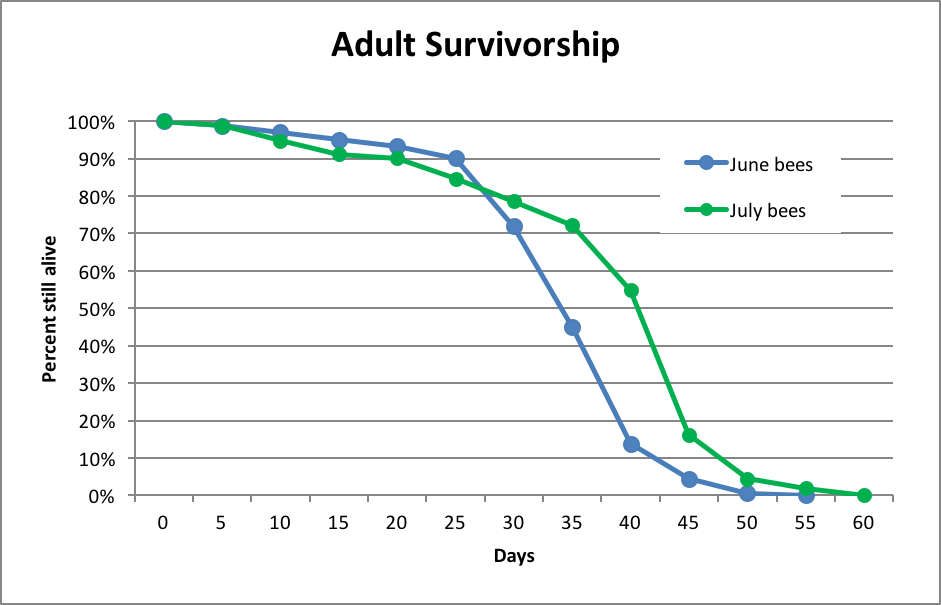

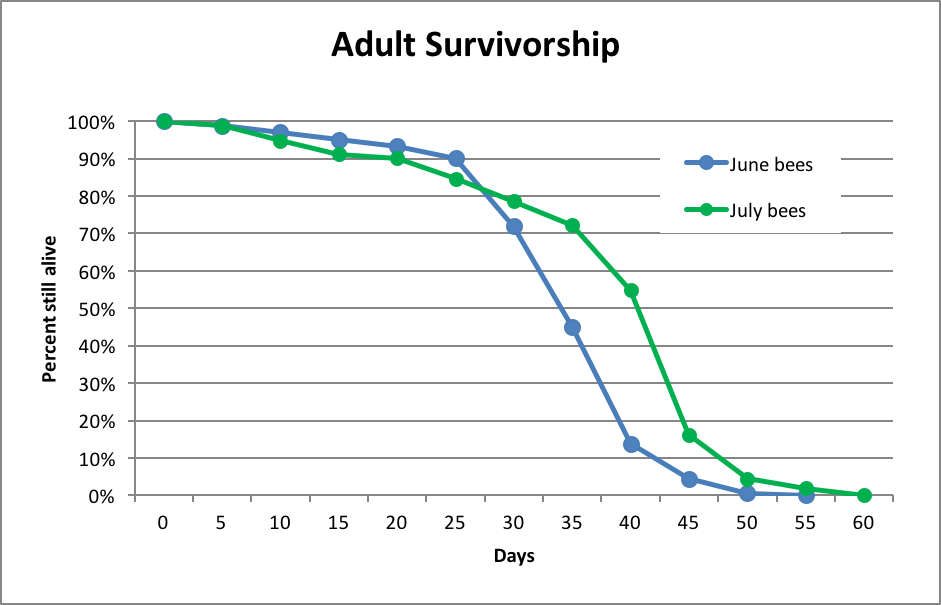

This information is useful, but we need to know more than the simple estimate of average worker longevity. What we really need to know is the day-by-day rate of attrition of any cohort of bees at various times of the year. Few researchers have dedicated serious time to finding the answer to this question. One of the best data sets is that of Sakagami and Fukuda [4] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Worker bee survivorship of Italian-type bees in Japan, after Sakagami (1968). The main honey flow (clover) occurs in June, and appeared to shorten the lives of workers due to increased foraging.

Let’s now compare the above to Lloyd Harris’ even more extensive data from Manitoba a decade later (Fig. 3):

Figure 3. Worker bee survivorship of Italian-type bees in Manitoba, after Harris [[i]; raw data courtesy the author]. Note how remarkably similar were the survivorship curves for Italian-type workers during June in either Japan or Manitoba. Harris found this survivorship curve to be consistent from April through August.

[i] Harris, JL (2010) The effect of requeening in late July on honey bee colony development on the Northern Great Plains of North America after removal from an indoor winter storage facility. Journal of Apicultural Research and Bee World 49(2): 159-169.

These data sets strongly suggest that worker survivorship is relatively constant over the course of the summer. So we now know how much attrition to subtract from recruitment. Let’s go back to the math!

A Simplified Mathematical Model

Question: Why does it seem to take a colony only 6-10 weeks to reach maximum population?

Question: And then why does the population seem to stop growing after 10 weeks?

In order to attempt to answer the above questions, I created the simple Excel spreadsheet shown in Table 1. In the yellow cells, I can enter the initial starting population of adult bees, and also the number of adults emerging per day (I used the term “eggs per day” since it better reflects the influence of the queen [6]). And then, applying Harris’ percentages of surviving bees at each 12-day time point (thanks to Lloyd for sharing his original data), I had the spreadsheet calculate the number of bees in each 12-day age cohort still expected to be alive at each future time point. Then I simply added each column in order to obtain the total colony population at each time point.

|

10,000 |

Starting population of adult bees |

|

1000 |

Eggs per day 12 days previous |

|

12,000 |

Amt sealed brood 12 days previous |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Day |

0 |

12 |

24 |

36 |

48 |

60 |

72 |

84 |

96 |

| 0 |

10,000 |

9,523 |

7,574 |

4,756 |

2,219 |

562 |

47 |

1 |

0 |

| 12 |

|

12,000 |

11,424 |

9,204 |

5,700 |

2,664 |

672 |

56 |

1 |

| 24 |

|

|

12,000 |

11,424 |

9,204 |

5,700 |

2,664 |

672 |

56 |

| 36 |

|

|

|

12,000 |

11,424 |

9,204 |

5,700 |

2,664 |

672 |

| 48 |

|

|

|

|

12,000 |

11,424 |

9,204 |

5,700 |

2,664 |

| 60 |

|

|

|

|

|

12,000 |

11,424 |

9,204 |

5,700 |

| 72 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12,000 |

11,424 |

9,204 |

| 84 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12,000 |

11,424 |

| 96 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12,000 |

| Total |

10,000 |

21,535 |

31,022 |

37,420 |

40,595 |

41,614 |

41,783 |

41,806 |

41,818 |

Table 1. Calculation of colony buildup over time based upon the queen’s egglaying rate and Lloyd Harris’ adult survivability curve. Illustrated is an example for a colony starting at 10,000 bees, with a queen laying 1000 eggs per day. Note that at about 60 days the birth rate and death rate reach equilibrium, and the colony essentially stops growing.

What struck me when I created this spreadsheet is that the rate of recruitment and the rate of attrition consistently reach equilibrium at about 60 days after the broodnest is fully established. Think about it– assuming that the queen’s rate of egglaying remains constant, but that the adult population continues to grow, then at some point the daily rate of attrition of the increasing adult population will match the daily rate of recruitment. At that point, the birth rate and the death rate reach equilibrium, and will remain so until either the birth rate or death rate changes.

But wait, you say, what about the influence of the starting population? Of course, a colony with a larger initial broodnest (such as a strong overwintered hive) gets a jump start, and can grow to its maximum in about 6 weeks (42 days). But the interesting thing is that after 10 weeks (70 days) of normal attrition, there are only a negligible amount of bees remaining from any initial adult population, meaning that the size of any starting population is irrelevant by that time.

Practical application: Surprise, surprise—the colony reaches maximum population at about 60 days after the broodnest is fully established—in agreement with the common beekeeper experience that it takes about 6 weeks for an overwintered colony to build up, or 10 weeks for a package. Those rules of thumb are based upon simple arithmetic.

Population Top Out

Question: What determines the maximum size to which a colony will grow?

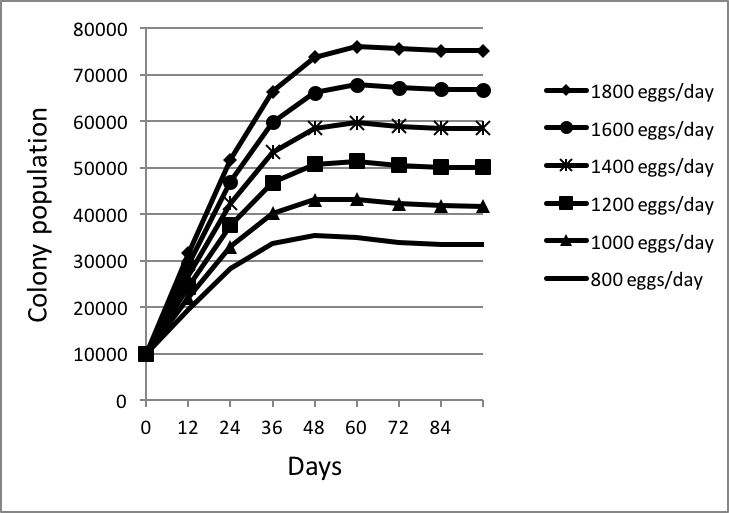

I then used my spreadsheet to calculate the ultimate equilibrium population reached at various rates of egglaying (Fig. 4):

Figure 4. I arbitrarily started each colony at 10,000 bees [[i]], with sealed brood emerging at the indicated rates of egglaying. Keep in mind that by 60 days, normal attrition would have caused the initial 10,000 adult bees to have dwindled to less than 600, thus having little influence on the overall colony population. Note that, at any egglaying rate, colonies reach an equilibrium maximum population at about 60 days after brood begins to emerge at the rate of the queen’s laying capacity.

[i] The size of the starting population makes no difference.

Conclusion: based upon Lloyd’s survivorship curve, which appears to be quite consistent from mid spring through late summer, a healthy, well fed colony will rapidly grow in about 60 days to its maximum size, which will be roughly 42x its daily recruitment (number of workers emerging per day). E.g., at an egglaying rate of 1000 per day, a colony will reach equilibrium at about 42,000 bees (which is consistent with measurements by a number of researchers).

Practical application: Poor nutrition or brood disease will reduce the percentage of the queen’s eggs that make it to adulthood, and nosema or extremely heavy foraging will reduce adult survivorship. Either factor will reduce the ultimate equilibrium size of the colony’s population (or prevent it from building altogether).

Playing Catch Up

Question: Then why can weak colonies sometimes catch up with those that got a head start?

Again and again I’ve seen some of the dinks that I leave behind when I move my strong colonies to almond pollination in early February, grow so rapidly in strength that they’ve caught up with the strong colonies by the time I bring them home several weeks later. And Russian or Carniolan bees, which overwinter with much smaller clusters than my Italians, often manage to explode their populations to match those of the Italians in time for the honey flow. But if population growth is linear, how can a weak colony catch up with a strong colony?

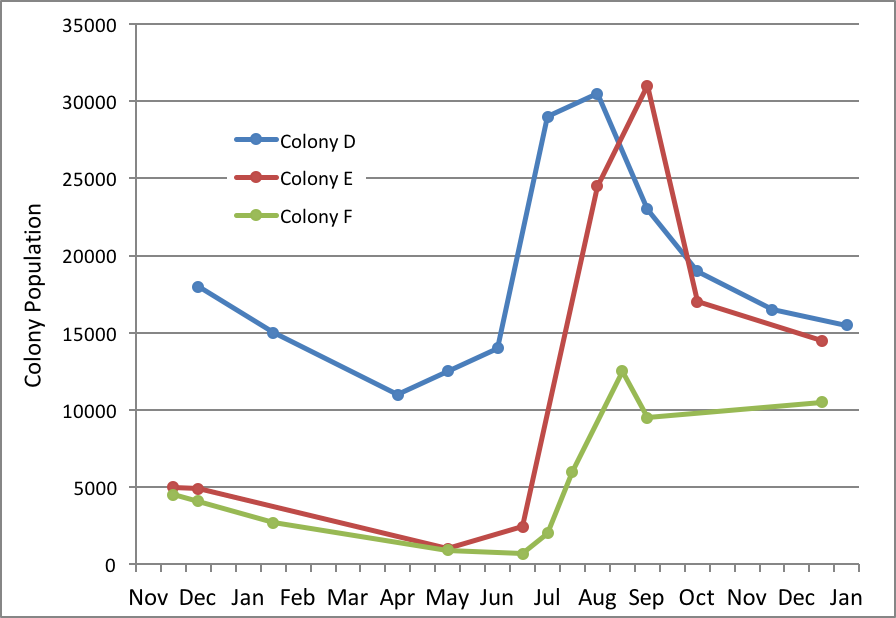

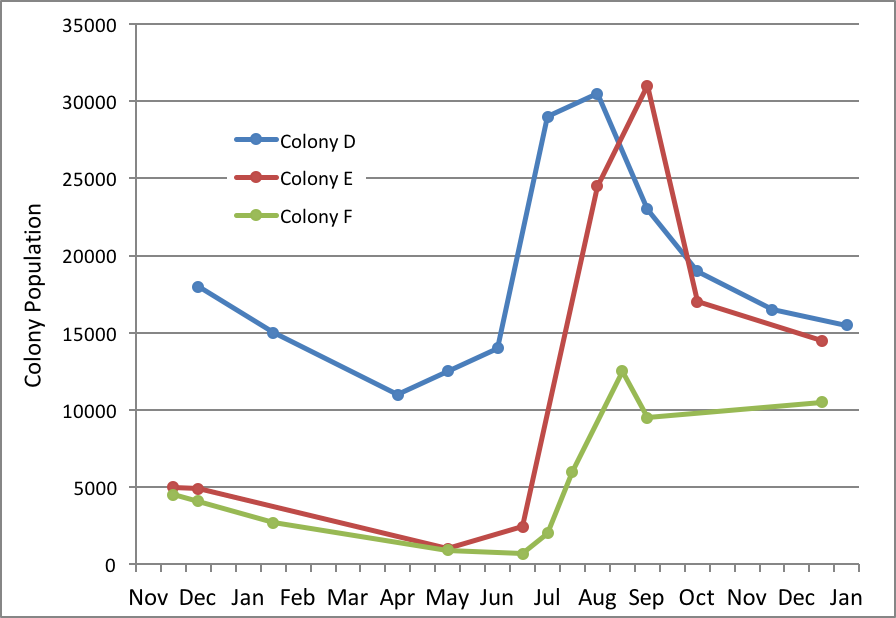

I’m hardly the first to ponder on this; Jeffree published a graph of the buildups of three colonies in Scotland in 1947 to illustrate the point [8](Fig. 5).

Figure 5. The year 1947 was exceptionally good for bees in Aberdeen, but not all colonies fared equally well. Note how all three colonies declined in late winter, pulled off successful spring turnovers, and grew linearly to their respective maximum strengths. However, only Colony D reached full strength in time to effectively take advantage of the main flow—producing 229 lbs of surplus honey. After Jeffrey [[i]].

[i] Jeffrey, EP (1959) Op cit, Figure 3.

Colony D came through the winter with a decent cluster size, pulled off a successful spring turnover in May, and reached a modest 30,000 bees (about 16 frames) in time to produce 229 lbs of surplus from the main honey flow. Colony E started tiny, yet still pulled off a successful spring turnover, catching up with D about 5 weeks later, and made 132 lbs (having missed hitting full strength in time for the main flow). On the other hand, poor little Colony F (690 individual bees at its low point) struggled with its spring turnover, and was unable to grow large enough to take advantage of the main honey flow (making only 28 lbs), but still reached an acceptable size for wintering by the end of the season.

So how the heck was Colony E able to catch up with D? The answer can again be explained by the math in Table 1 and by looking at the growth curves in Fig. 4. Once a colony establishes a broodnest large enough for a queen to hit her laying capacity, it indeed grows at a linear rate, but then slows way down at about 48 days. That slowdown causes colonies with head starts to lose their lead, allowing colonies s lagging slightly behind to catch up. Secondly, if a late-starting queen lays even 100 more eggs per day than an early starter, her colony will gain nearly 4000 bees more than the early starter over the next 48 days.

But lastly, if the colony is unable to complete a strong spring turnover early enough, it really misses the boat, and will be unable to grow strong in time for the main flow. Thus, colonies coming out of winter fairly strong at first spring pollen will generally have a leg up on weaker ones. But as anyone who has watched a hive of Russian bees explode in strength can confirm, some races of bees are adapted to later springs, and more rapid buildup.

Practical application: timing is everything. Unless the colony synchronizes its buildup to reach peak at the beginning of the main flow, it won’t be able to take full advantage of that honey flow. Our goal as beekeepers is to manage our colonies for such synchronization. If they are strong too early, they may swarm; and if too late, won’t be able to produce a surplus.

I’m acutely aware of this issue this season, since our local flora is flowering 2-4 weeks earlier than usual. We have a management plan based upon splitting our hives shortly after they return from almonds and have grown to the size that they are thinking of swarming. But this season, the forage that we depend upon for the buildup of our splits had already finished flowering before the colonies were ready to split. And now we’re facing the likelihood of an early main flow, followed by an abnormally long summer drought. We’ve been busting our butts trying to keep up.

Next

Causes of hiccups in colony buildup.

Acknowledgements

I again wish to express my gratitude to Lloyd Harris for sharing his data set. And of course to Peter Borst for his assistance in literature research. And there is no way that I could justify taking the time to research and write these articles without the generous donations by beekeepers to ScientificBeekeeping.com.

Citations and Footnotes

[1] Specifically, the amount of sealed brood, which underestimates the actual rate of egglaying.

[2] Borst, PL (2013) How long does a honey bee live? ABJ 153(3): 241-244.

[3] Woyke, J (1984) Correlations and interactions between population, length of worker life and honey production by honeybees in a temperate region. J. of Apic. Res. 23(3): 148-156.

[4] Sakagami, SF & H Fukuda (1968) Life tables for worker honeybees. Res. Popul, Ecol. X: 127-139.

[5] Harris, JL (2010) The effect of requeening in late July on honey bee colony development on the Northern Great Plains of North America after removal from an indoor winter storage facility. Journal of Apicultural Research and Bee World 49(2): 159-169.

[6] Actual worker survival from egg to larva is around 90% in unstressed colonies, so these figures actually underestimate the numbers of eggs laid by the queen. Fukuda, H. and Sakagami, S.F. 1968. Worker brood survival in honeybees. Res. Popul. Ecol. 10: 31-39.

[7] The size of the starting population makes no difference.

[8] Jeffree, EP (1959) The size of honey-bee colonies throughout the year and the best size to winter. A lecture given to the Central Association of Bee-Keepers

[9] Jeffrey, EP (1959) Op cit, Figure 3.