The How and Why of Oxalic Vaporization: Part 2

January 2, 2026

Contents

WOULD MAINTAINING A LOWER TEMPERATURE REDUCE DEGRADATION? 6

SECOND-BY-SECOND OXALIC ACID OUTPUT 9

HOW MUCH FORMIC ACID IS IN THE OUTPUT? 15

SO WHAT’S THE OPTIMAL START-POINT TEMPERATURE? 20

HOW DO THE OXALIC OUTPUTS OF VARIOUS VAPORIZERS COMPARE? 22

IT’S IMPORTANT WHERE YOU AIM 23

CONSIDERATIONS AND TRADEOFFS IN VAPORIZER DESIGN 26

The How and Why of Oxalic Vaporization

Part 2

First Published in ABJ November 2025

Randy Oliver and János Fenyősy

ScientificBeekeeping.com

Some beekeepers swear by one type of oxalic acid vaporization (OAV) device or another, whereas others have been disappointed. Part of the problem may be that only a portion of the acid that you put into a vaporizer actually comes out the other end!

Any device’s efficacy at controlling varroa depends upon how efficiently it gets the acid onto the bees (and eventually the mites). Last month we gave the basics on oxalic acid vaporization: you heat up a measured load (dose) of oxalic acid, and out comes a huge cloud of white fog. But not all of that fog consists of vaporized oxalic acid — dependent upon design and temperature, a portion of it may be only decomposition products of the original dose.

As I mentioned in our previous article, I had been surprised at this fact years ago when I directed the output of a vaporizer into a balloon. Then last year I was spurred into going deeper when I got an email from János, Fenyősy asking me to independently confirm his own findings. Assisted by my helpers Rose and Corrine, I did so, independently developing methods and fabricating my own testing apparatuses by trial and error (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 János had more space and budget than I had available. The contraptions that I built weren’t nearly as elegant, but still confirmed his findings.

In this article I’ll focus upon how we tested at my place, walking you through our discovery process.

TESTING THE VARROX

The pan-type Varrox starts cold, then boils off the oxalic as it heats up (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 In practice, the pan is placed on the bottom board directly below the cluster. Unlike as with the gun-type vaporizers, the Varrox starts cold. As it heats, the oxalic slowly melts, then boils, then a cloud of oxalic vapor rises (theoretically allowing it to vaporize before it gets to degradation temperature). The pan eventually gets quite hot towards the end of the vaporization process.

Practical warning: Don’t leave a Varrox in the hive once the oxalic has vaporized – it can burn into a wooden bottom board, and the smoke can cause serious bee kill (I found this out the hard way)!

Since the Varrox doesn’t have an exhaust tube, capturing its output was tricky (Figures 3 & 4).

Fig. 3 I finally figured out how to clamp a copper bell reducer over the Varrox pan (without or with a silicone washer), then direct the exhaust into my chilled copper U-tube, or directly into a large ballon containing frozen distilled water.

Fig. 4 Most of the oxalic recrystallized in the bell reducer immediately above the heating pan (we combined both this, plus any residues in the ice water-jacketed tube and balloon for titration).

Despite the fact that the oxalic is slowly heated, our flame observations indicate that substantial thermal decomposition still occurs (Figure 13). Our results are shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 5 We put 4 grams of oxalic into the Varrox, but the output (including any formic) titrated to be only around 50% of the acidity of the 4g inputted amount.

Experimental note: In our many titrations with any vaporizer, we consistently observed variation in percent acid output for each run, despite placing exactly the same oxalic loads, and vaporizing at the same temperature. This may be due to tiny details (such as the effect of residues in the chambers, or the manufacturer’s placement of the thermistor in the device), but likely reflect what would occur under field conditions.

So my next question was…

WOULD MAINTAINING A LOWER TEMPERATURE REDUCE DEGRADATION?

Since OA doesn’t appear to degrade to any considerable extent below 190°C, why not simply set a vaporizer to operate below that temperature? To answer this question, we experimented quite a bit (using gun-type vaporizers with adjustable setpoint temperatures), starting either cold or hot (Figure 6).

Fig. 6 It was a pain, but we were able to capture the output of a vaporizer set at 190°C (the temperature of the chamber’s base, rather than the circular heating element). We found that at that low setpoint temperature, the vaporized OA immediately recrystallizes above the heating element and can clog the output tube (which can cause the cap to explode off!). So we went back to a bell reducer above the heating chamber (in which most of the vapor again recrystallized).

It didn’t make much difference whether we started cold or hot, since in either case, the acid tends to lift up on the steam as it’s heated, and stay suspended above the heating element. János filmed a video of what happens at [[1]]; compare that to what occurs if the vaporizer is set at 230°C [[2]].

Preliminary findings: keeping the temperature below 190°C didn’t appear to reduce thermal decomposition (perhaps because it extends the amount of time that the melted acid is “cooking”). Plus at low temps it’s difficult to prevent the OA from clogging a gun-type vaporizer.

THE LEIDENFROST EFFECT

Our observations that the oxalic acid crystals or tablets put into a vaporizer often get elevated above the heating surface (thus eliminating direct contact) brings to mind the “Leidenfrost Effect”:

The Leidenfrost effect is a physical phenomenon in which a liquid (or solid), placed onto a hot surface that is significantly hotter than the liquid’s boiling point, produces an insulating vapor below it. Because of this repulsive force, the liquid (or solid) levitates up and hovers over the surface, no longer making physical contact with it, which prevents it from rapidly boiling off.

Practical application: You’ve likely observed the Leidenfrost Effect when you drop water onto a hot griddle — the drops skittle around, elevated on the steam jetting off their bottoms. Despite the griddle being at well above the vaporization temperature of water, the fact that the drops remain liquid means that the water in them has never reached boiling point (ditto if you place a piece of dry ice (solid carbon dioxide) onto a hot surface). Similarly, the Leidenfrost effect may prevent some of the solid oxalic acid placed into a vaporizer from immediately vaporizing.

When started cold, the boiling-off of the water of crystallization lifts the oxalic acid, which may recrystallize immediately above the boiling liquid, leaving a gap. What I wondered was whether when one drops a load of oxalic into a hot chamber, would the acid also float on a layer of steam — the steam being at around 135°C, far below the temperature of thermal decomposition? In either case, this Leidenfrost Effect might reduce the amount of thermal decomposition – even when the oxalic is dropped into a very hot chamber.

To take a closer look, I dropped EZ-OX tablets onto a heated iron plate (I had to place a wire basket around them to keep them from skittling off), then observed them from the side (Figure 7).

Fig. 7 When dropped onto a hot plate, an EZ-OX tablet immediately lifts up and hovers above the hot surface, elevated on the steam blasting off its lower surface, then eventually drops and melts down.

Practical application: János has found that the Leidenfrost Effect is more apparent in a new vaporizer with polished metal on the heating surface, than it is after the vaporizer’s been used a few times.

SECOND-BY-SECOND OXALIC ACID OUTPUT

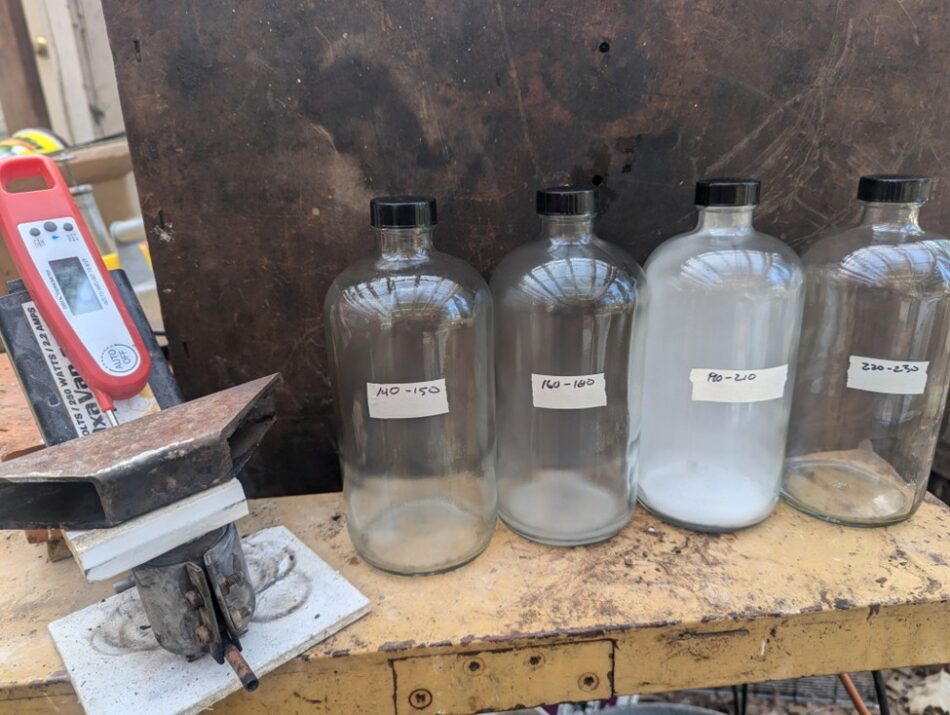

Wanting to collect the output of a vaporizer second-by-second, we put a bunch of empty narrow-mouth 1-liter bottles into the freezer, and then lined them up to individually capture the output from a vaporizer by chamber temperature at 5- or 10-second intervals (Figures 8 & 9).

Fig. 8 Captures at different vaporization chamber temperatures (as measured by a digital thermometer inserted into the heating chamber) — from 140-150, 160-180, 190-210, and 220-230°C Notice that virtually all the oxalic output occurs in the 190-210°C range – exactly at when most thermal decomposition is also occurring! (Note: any decomposition gases present in the jars would not be visible).

It’s not clear whether the production of oxalic vapor correlates with the fact that the melting point of anhydrous oxalic acid is around 190°C. We don’t know whether that’s a coincidence, since the oxalic acid is already dissolved in the hot water.

Terminology note: We often hear of oxalic acid “sublimation.” Sublimation is when a heated solid skips the transition into a liquid before jumping into the gas phase. Since when heated, the oxalic acid dihydrate melts into a liquid aqueous solution before beginning to vaporize, I question whether sublimation is the correct term to use.

Fig. 9 Rose showing how we could then titrate the amount of acidity in each bottle. See some results in Figure 10.

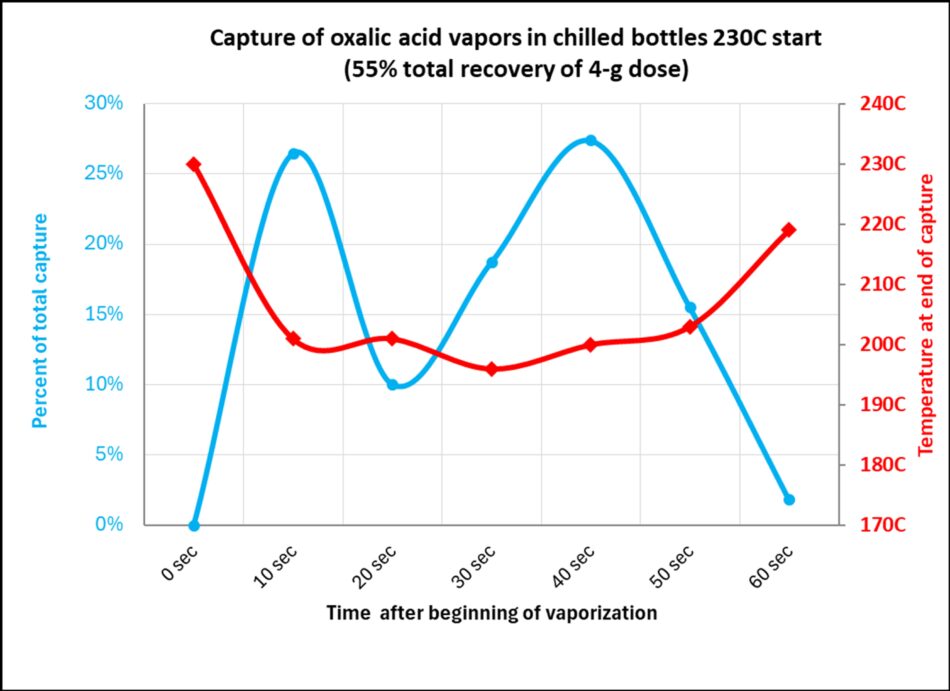

Fig. 10 At 230°C starting temperature, the oxalic acid quickly boils and vaporizes nearly half of the output during the initial flash off (blue plot), but that boiling temporarily cools the heating chamber (red plot), causing a brief pause in vaporization (which quickly resumes as the chamber reheats). The temperature then rises as the last of the oxalic vaporizes. The entire process takes only 60 seconds!

Note: The data above was for a Provap 110 starting at 230°C.; a vaporizer with a greater thermal mass would not experience as much of a temperature drop. The output progress may be different at a higher starting temperature. Refer back to the temperature drop data in Figure 20.

This bottle capture method worked so well, and the results were so easy to visualize, that we repeated it with more bottles (Figures 11).

Fig. 11 Corrine helped us to collect vapor output into chilled bottles at 10-second intervals, again recording the temperatures in the vaporization chamber. Although we captured visible fog over the entire duration, it’s easy to see when the vapor contains oxalic acid — most OA exited between 180 and 210°C, with vaporization being completed by 220°C

SUMMARY OF OUR FINDINGS

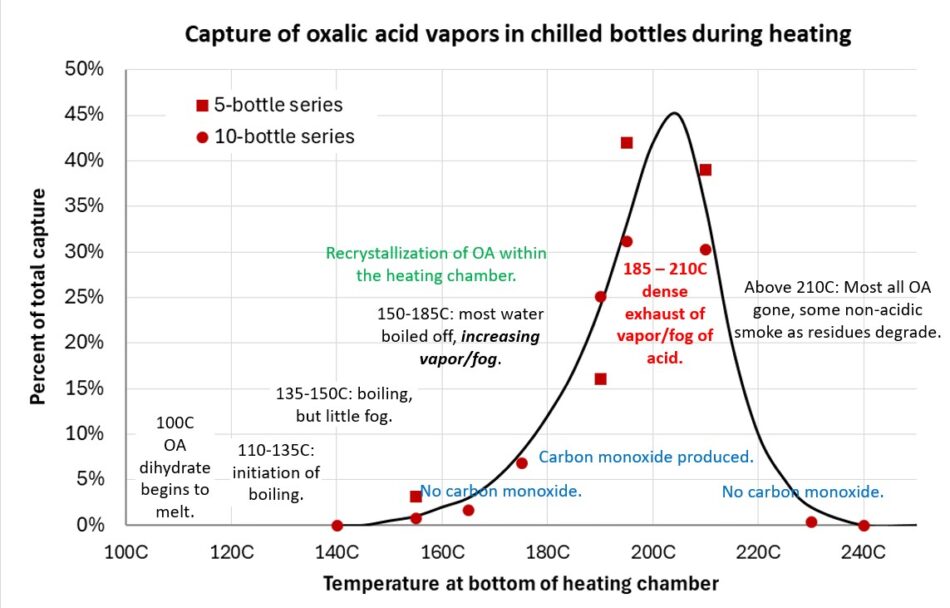

I compiled what we’ve learned into a chart (Figure 12).

Fig. 12 Starting with a cold chamber, his chart shows the progress of oxalic vaporization as the load slowly heats up. When dropped into a hot chamber, the first steps occur very quickly and the entire process may take only seconds.

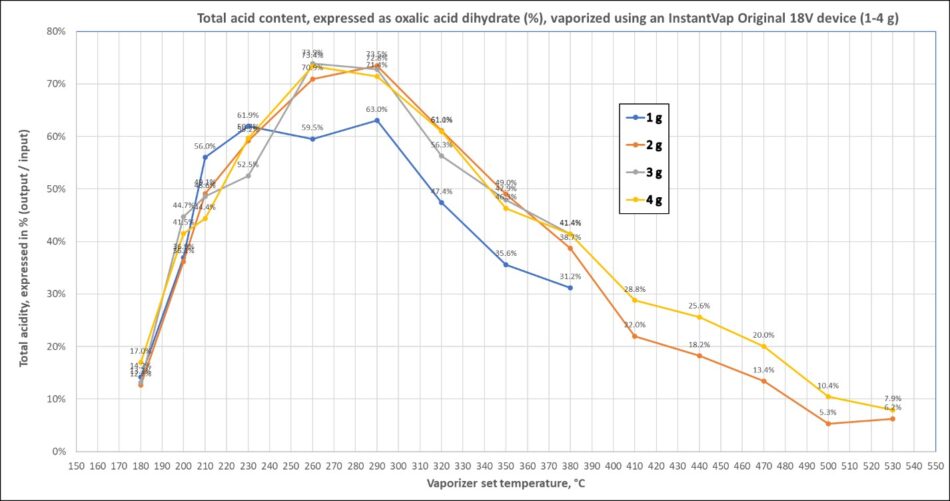

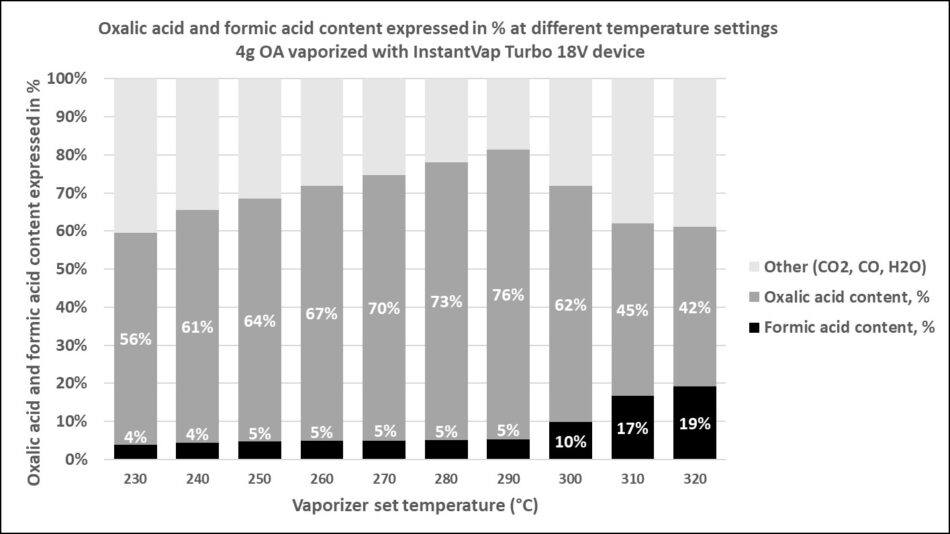

But beekeepers will usually be starting with an already- heated vaporization chamber. János ran a full series of titrations over a wide range of range of starting setpoint temperatures, vaporizing from 1 to 4 grams of oxalic acid (Figure 13).

Fig. 13 Perhaps surprisingly, at low setpoint temperatures, total acid output is lower than at midrange temperatures, peaking between 260 and 290°C. But any hotter, total acid output decreases. (the ladies and I got similar results in our tests).

The above graph is for total acid output, which would include any formic acid produced as a decomposition product.

Practical application: Titration measures acidity — whether from oxalic or formic acid. So if you’re solely interested in how much oxalic is coming out, prior to rinsing out the recrystallized oxalic for titration, dry air should be blown through the collection tube to evaporate any formic.

And speaking of formic…

HOW MUCH FORMIC ACID IS IN THE OUTPUT?

This is a common question. In our previous article, I showed the potential chemical paths of oxalic acid thermal decomposition, with one involving formic acid. The temperature range over which decomposition occurs can easily be seen by the inflation of a balloon, or by the flame produced by igniting the carbon monoxide decomposition product (formic or oxalic acid vapors don’t ignite) (Figure 14).

Fig. 14 It’s also easy to track exactly when oxalic acid is decomposing into carbon monoxide! If I hold a lighter under the vent, ignition only occurs between 190 and 210°C (the same temperature range in which most oxalic vaporization occurs).

I mentioned to János that we didn’t smell any formic acid in our test bottles, but he wondered whether formic acid might be produced at higher temperatures. To determine how much formic acid might be in the output vapor, we independently tested by capturing vapor output into cold water (so that any formic acid would dissolve into it), then splitting that solution into two equal portions – titrating one portion immediately, and the other portion after it had air dried (which allows any formic acid to evaporate) [[3]]. From the amount of any decrease in acidity due to drying, we could calculate how much formic acid was in the output vapor.

For my first preliminary trial test, I ran the vaporizer at two different setpoint temperatures (Figure 15 and Table 1).

Fig. 15 I was surprised by how different the crystals looked after evaporating the collection water from vaporizations made at different temperatures. I do not know what chemistry is involved.

| Vaporizer | Intro temp | g OA | Titration | % output | Total |

| Instantvap | 180C | 4.6 | immed half of output | 12% | 24% |

| 180C | 4.6 | dried half of output | 12% | ||

| 250C | 4.9 | immed half of output | 22% | 42% | |

| 250C | 4.9 | dried half of output | 20% |

Table 1 Although there was no evidence of formic in the 180°C output, and scant evidence for it at 250°C, there was a heckuva lot more oxalic in the 250°C vaporization.

But János suggested that I try it at higher temperatures, so we performed four runs at 400°C (Table 2).

Table 2 Bingo! At 400°C, the median percent of acid output due to formic was 16%. I do not know why run B was an outlier – but we got used to having outliers in all our oxalic capture runs.

This finding that formic acid was present at high temperatures surprised us (since we hadn’t noticed any odor at the lower temperatures that we’d been testing at), so I vaporized some OA into two different bottles – one with the vaporizer set at 230, and the other at 400°C. I knew from our experience with formic pads that Rose’s nose is very sensitive to its odor, so asked her to sniff the bottles after they had cooled (Figure 16).

Fig. 16 This simple bioassay indicated that formic acid is indeed a byproduct of vaporizing at too high a temperature. Try it yourself!

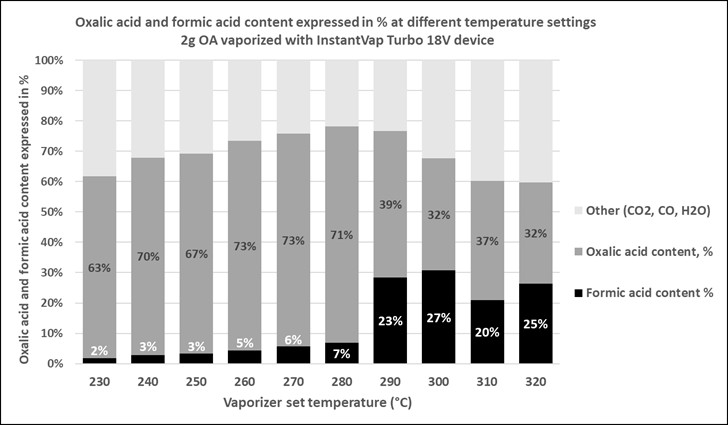

János went much further – determining the percent formic output over a wide range of temperatures (Figures 17 & 18).

Fig. 17 János’ data indicates that the reason that we hadn’t been smelling formic acid was that little formic acid is produced until the vaporizer setpoint temperature is above 290°C.

Fig. 18 At 2g doses, the increase in formic production is much more dramatic, perhaps due to less cooling of the chamber.

Practical application: The performance of a vaporizer varies with the dose of oxalic dropped in. You may need to adjust the setpoint for each specific dose.

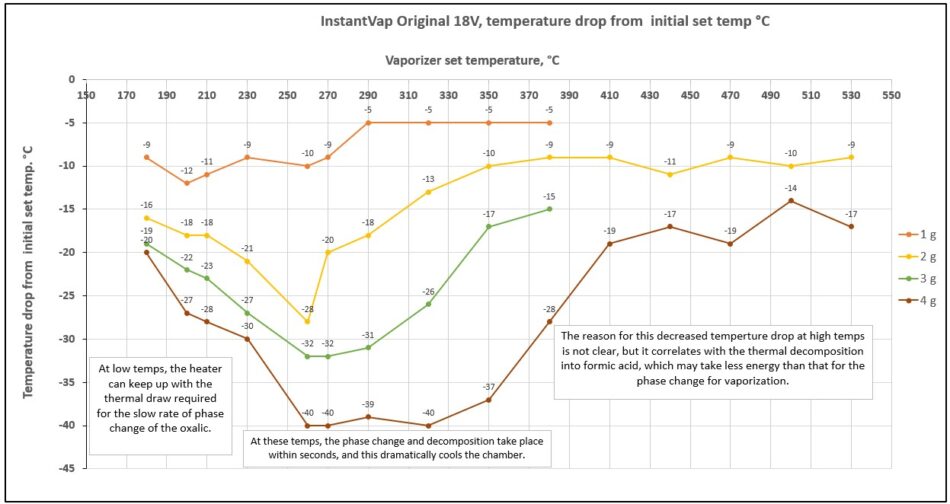

So what’s the deal with the transition from thermal decomposition into carbon monoxide to formic acid? Remember the temperature drop of the heating chamber shown in Figure 10? János made an intriguing graph of the degree of temperature drop of the heating chamber (which reflects how much energy is transferred to the vaporization process), when the oxalic acid is dropped into it over a wide range of starting temperatures (Figure 19).

Fig. 19 The temperature drop of the heating chamber reflects the amount of heat required for the vaporization of the OA vs the fixed output of the heating unit. As expected, there is more temperature drop with larger loads. Since the oxalic acid visually appears to vaporize more quickly at higher temperatures, we’d expect the temperature drop to increase — but it doesn’t! We can’t yet explain why, but suspect that it might be that thermal decomposition into formic takes less energy than a phase change.

As expected, the more OA placed into the chamber, the greater the heat demand. But this doesn’t explain why at very high temperatures (at which the OA is vaporized very quickly) the temperature drops less than it does at lower temperatures.

Practical application: We still have much to learn about the processes that take place during oxalic acid vaporization!

User beware! Running a vaporizer at a high temperature may get the OA to vaporize in a moment, but at the cost of degrading a substantial portion of the oxalic into formic acid (although hardly enough to have much effect upon the mites).

SO WHAT’S THE OPTIMAL START-POINT TEMPERATURE?

Unlike with pan-type vaporizers, which are allowed to cool between each vaporization, in gun-type vaporizers, the oxalic dose is generally dropped into the device after it’s reached its setpoint temperature.

So the most important question appears to be: What’s the optimal setpoint temperature, with regard to minimizing the time required to apply a vaporization, and maximizing the amount of oxalic acid that makes it into the hive? The evaluation of some sets of data may help us to answer that question (Figure 20).

Fig. 20 This compilation of five separately-sourced sets of data follow the same curve [[4]]. The proportion of the inputted oxalic acid that makes it out of a vaporizer undegraded is clearly a function of the setpoint temperature. Even at the best, you can’t expect more than 60% of what you put in to come out intact.

Practical application: It appears that the optimal setpoint temperature lies within the range between 240 and 280°C (465 – 535°F). But these higher temperatures require more energy, which is problematic for battery-powered vaporizers.

A Surprise: What surprised me is that, contrary to what I expected, lower temperatures were to no advantage, and that setpoint temperatures above the 190 – 210°C range (where the most carbon monoxide decomposition product is produced), actually produced the highest output of oxalic acid!

But as expected, there was a limit, and as the setpoint temp increases above 290°C, oxalic output starts to drop off (due to increased thermal degradation).

How can we explain the above? Good question! I’m guessing that it goes like this:

- Setpoint below 190°C: the oxalic spends more time “cooking” in its melted (or recrystallized) state in the chamber (apparently decomposing into CO2 and water, since we don’t detect carbon monoxide).

- Setpoint 190 – 210°C: at this temperature, we observe maximum production of carbon monoxide.

- Setpoint 210 – 235°C: carbon monoxide production drops off, and OA begins to decompose into non-acid components (CO2, H2O). A low quantity of formic acid is also formed

- Setpoint 235 – 275°C: in this range, the Leidenfrost Effect may produce a blast of superheated steam that percolates up through the oxalic to effect rapid vaporization.

Setpoint above 275°C: thermal decomposition steps up (now into formic acid), and less oxalic makes it out intact.

HOW DO THE OXALIC OUTPUTS OF VARIOUS VAPORIZERS COMPARE?

I had four different vaporizer types on hand, so out of curiosity compared their total acid outputs from 4g loads, under the same conditions, and for the guns, all with setpoint temp of 230°C (Figure 21).

Fig. 21 We performed several runs each with a 12V Varrox, an 18V InstantVap Original, and 120V Provap 110 and Lorobbees units. All gave oxalic outputs in roughly the same range (with a few higher values from the Varrox). Note that we measured total acidity, which would have included any formic (although at the setpoint temperatures, I wouldn’t expect that much was produced).

Practical application: this test of some of the most commonly-used vaporizers suggests that due to unavoidable thermal decomposition, it looks as though we can expect to get around 50% of an inputted dose of oxalic acid into a hive. This is not a problem, but rather something to keep in mind: THE DOSE THAT YOU PUT INTO A VAPORIZER IS NOT THE DOSE THAT THE BEES ARE EXPOSED TO! So you can’t assume that an oxalic dose applied by vaporization is the same as one applied by dribble.

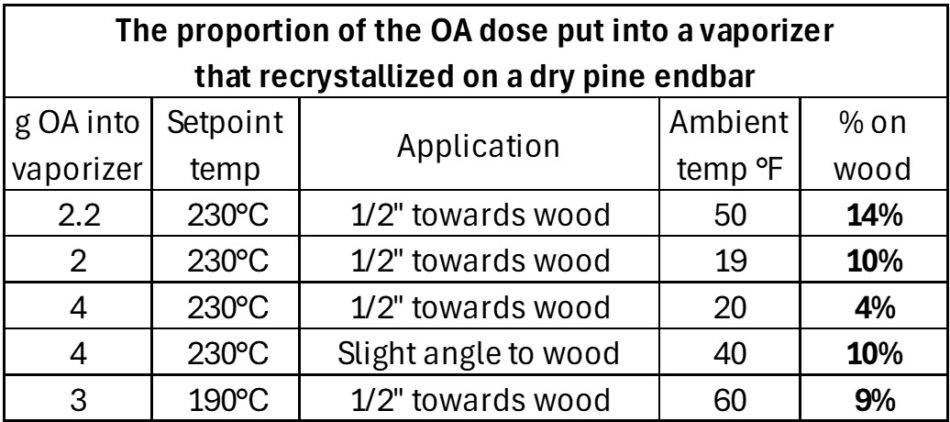

IT’S IMPORTANT WHERE YOU AIM

It’s not just the bullet, it’s important where you aim it! I first noticed this on the bottom board (Figure 22).

Fig. 22 It’s easy to see the fog coming out of any openings in a hive, but you should look inside afterwards to check your aim. If the vapor stream happens to be aimed slightly towards the bottom board, that acid will not get on the bees.

Update: Another photo of a stream of OA vapor that crystallized when it lost heat to a wooden surface. It only amounted to a fraction of a gram, but every bit counts towards efficacy!

This made me curious about recommendations to drill a hole in your hive for the insertion of the vaporizer exhaust tube, so I ran some tests (Figure 23 & Table 3).

Fig. 23 I spaced frame end bars the distance that they’d be from the hive wall, and then shot a vaporizer at them.

Table 3 Considering that only around 50% of the oxalic dose comes out of a vaporizer, losing another 10% on the wood would mean that only 40% of the applied dosage actually had a chance to get on the bees.

Practical application: When I hear the recommendation to drill a hole in the hive to insert the vaporizer output tube for winter vaporizations, I cringe. If the brass or copper tube touches cold or wet wood inside the hole, it will chill, and acid crystals may condense within (or at the tip of) the tube. And then if the vapor stream strikes a cool endbar, part of it will recrystallize there, and never reach the bees. Ditto with a cold towel placed on either side of an outlet tube placed in the hive entrance (check yourself to look for a lump of white crystals on the towel). This issue can especially be problematic with low doses in cold weather.

CONSIDERATIONS AND TRADEOFFS IN VAPORIZER DESIGN

The concept of building a device that can vaporize oxalic acid is simple, but there a number of important factors to take into consideration (thanks to János for explaining these to me):

- The most important may be the setpoint temperature (the temperature of the heating chamber when you drop in the OA). János has some stunning videos of the process of vaporization in the heating chamber at different starting setpoint temperatures [[5]].

- The chamber must also have enough thermal mass to prevent the inputted OA from causing too large a temperature drop when its water boils off or the acid vaporizes (this issue is exacerbated when one applies larger loads). The tradeoff being that more mass means that it will take more time and energy to heat it.

- The volume and heating surface area of the vaporization chamber into which you drop a load of OA crystals or tablets, as well as the type of metal (since each metal or alloy has different heat transfer properties, as well as catalytic influence of the amount of thermal degradation of the OA). With large doses of OA, the chamber must have a large enough diameter to allow for effective heating of the mass of crystals.

- The sides and top of the heating chamber, as well as the exhaust tube, must be hot enough to prevent recrystallization of the vaporized OA inside (this is especially problematic at lower setpoint temperatures).

- The thermal output of the heating element, which determines how quickly the vaporizer can heat up or reheat for repeated cycles from hive to hive.

- An accurately-placed thermistor and temperature controller (this is a major potential problem with propane-fired vaporizers).

- The device must have a tight cover to seal the chamber, so that the vapor exits through an exhaust tube inserted into the hive. The cover must be easily openable, and securely seal (to avoid the pressure of the water vapor from blowing it off).

- An exhaust tube that doesn’t chill the vapor (which would cause clogging).

- Because a beekeeper may not read or fully understand the instructions, it’s likely best for a manufacturer to set minimum and maximum setpoint temperatures for the device.

Practical application: For maximal oxalic output efficiency, a vaporizer must strike a balance between rapid enough heat transfer so as not to prolong the decomposition time, but not so high (for rapid vaporization) that it increases the thermal decomposition of the oxalic or the production of formic acid. And it should come with a chart for the recommended setpoint temperatures for different loads of oxalic acid.

CONCLUSIONS

All oxalic vaporizers put out a white cloud of condensing vapor, but depending upon the factors above, unless you have titration data, you don’t know how much of that cloud consists of oxalic acid (relative to the dose that you put in).

The bottom line is that beekeepers worldwide are blindly using vaporizers without any idea of how much is oxalic acid is actually coming out of their devices, nor how much gets onto the bees (and mites). This is of special concern with very high-temperature devices, or with devices that treat multiple hives from a single large load of oxalic — is the applied dose of oxalic the same for each hive in the series?

Without standardized testing via titration, there’s no way to know what setpoint temperature to use, how effective a device is at applying a dose of oxalic acid, or whether you can treat multiple hives from one large dose.

Practical application: Beekeepers have every reason to demand titration data for every vaporizer offered on the market. Every seller should show actual titration data for their device’s output, preferably from an independent testing lab.

NEXT

We measured how much oxalic acid actually gets onto the bees from various application methods, and how long those residues persist.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was a group project, and I thank János, Markus Bärmann, Rainer Dickhardt, Barna Kovács, Larry Welle, Russell Smith, and the other beekeepers and manufacturers who responded to my questions. But most of all, I appreciate my assistants Rose Pasetes and Corrine Jones for all their help with our many vaporizations and tedious titrations.

NOTES AND CITATIONS

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XM-9jjWrLyY

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ciCtelTodLc

[3] Surprisingly, when evaporating from a beaker, formic acid remains in the water until the last drop evaporates!

[4] János’ figures are somewhat higher than mine, which may be due to our different methods of calculation (or something else).

[5] https://www.youtube.com/@instantvap5808