Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance: Part 5–It’s Your Turn

January 16, 2026

Contents

SO HERE’S A LIST OF SOME OPTIONS: 4

Option #1 (Take your breeders from Nature) 4

Option #2 (Rolling the dice) 5

Option #3 (the one that we took) 5

HOW MANY COLONIES DO I NEED?. 6

HOW SHOULD I CONTROL THE DRONE POOL?. 7

YOU GOTTA DO A LOT OF MITE WASHES! 7

results of this year’s testing. 8

SHOULD I USE INSTRUMENTAL INSEMINATION?. 9

SELECTIVE BREEDING IS A BALANCING ACT. 10

HOW OFTEN SHOULD I BRING IN OUTSIDE GENETICS?. 12

UNDERSTAND THE GENETICS INVOLVED IN MITE RESISTANCE. 12

Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance

Part 5: It’s your turn!

First Published in ABJ January 2026

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

We beekeepers have been futilely fighting varroa for nearly forty years, the problem being our dependence upon stopgap miticides, which has only prolonged our agony. It’s time to hand the job over to our bees themselves. Now’s your chance to be part of the solution!

I caught my first swarm as a teenager back in 1967, learning the ropes by apprenticing to an experienced beekeeper. I enjoyed beekeeping for 26 years before I saw my first varroa mite, but have now been living under its curse for 32 years. I’m sick of it (Figure 1), and long for “the good old days”!

Fig. 1 Sysiphus was sentenced to the eternal punishment of rolling a boulder uphill. Are we similarly doomed to labor every year to keep the danged mites under control, only to have to start over again each spring? Or can we instead free ourselves by handing that job over to our bees?

Kirk Webster wrote some prophetic words about his selective breeding of bees back in 2007 [[1]]:

The work might be hard, but only because we’re not used to it. If we care about future generations … we have to stop expecting other people to solve our problems; to learn from others instead of taking from them, and do our share of the work. This work is more satisfying and meaningful than just about anything else you can do at this point. The old beekeeping is dying, and a new one is struggling to be born. Are you going to the funeral, or assisting with the birth? They are both occurring at the same time, so you have to choose.

I choose to be involved in the rebirth of beekeeping in which varroa is a minor parasite, rather than our main problem. To do so, I began a demonstration project of a K.I.S.S. method for the selective breeding of bees naturally resistant to the mite. My sons and I have now been running this project for long enough to see a light at the end of the tunnel — as the percentage of our colonies that laugh at the mite grows each year.

SUPPLY FOLLOWS DEMAND

Some years ago, a large commercial beekeeper referred to most of the bee stock on the market as “mite candy,” since they were selected solely for rapid buildup and productivity, without also seriously selecting for resistance to varroa. Part of the reason is that up ‘til now, queen producers have been able to sell every queen that they produce, so there’s been little incentive for them to add mite resistance as a selection criterion. But after last season’s massive colony losses due to miticide failure, and the recent funding cuts to our USDA Bee Labs, the time may have finally come that beekeepers start to demand honey bee strains that are not only productive, but that can also deal with varroa on their own. Supply follows demand, and the time is ripe for a shift in the market.

Practical application: As our miticide options for efficacious varroa control become more limited (and expensive), our industry is in the midst of a transition in the methods that we use for mite management. Such a shift offers an opportunity for all queen producers to step up their game as our industry transitions from total dependence upon miticides, to using mite-resistance stock.

When we were surprised in 2015 to find that we already had a colony in our operation that kept mites under control by itself (our Queen Zero hive), I announced that I would run a demonstration project for the benefit of queen breeders everywhere, to see what sort of progress we could make by the simplest breeding program possible — by selecting potential breeders based upon not only performance, but also mite-wash counts. I’ve already detailed in previous articles much of what we’ve learned as our still-in-progress selective breeding program is coming to fruition. Now having nearly ten years of experience under our belts, I’m happy to offer some tips and suggestions to others who might want to hop on board and produce mite-resistant stock of their own.

SO HERE’S A LIST OF SOME OPTIONS:

Option #1 (take your breeders from nature)

While beekeepers, by using miticides, have held back the natural evolutionary process toward mite resistance in managed bees, in unmanaged populations, the selective hand of Mother Nature has been continuously at work. In a number of places around the U.S. and the world, free-living native or feral populations of bees already exhibit some degree of resistance (or tolerance) to varroa. You could start with them, and then select for workability and productivity, as well as mite resistance. The problem would be to control the feral drone pool, but at least any outmatings would come only from drones whose colonies survived varroa.

Practical application: Many small-scale beekeepers already do this. If your local feral stock is generally workable, just produce queen cells from your most mite-resistant and workable colonies [[2], [3]], and requeen the rest with those cells.

Option #2 (rolling the dice)

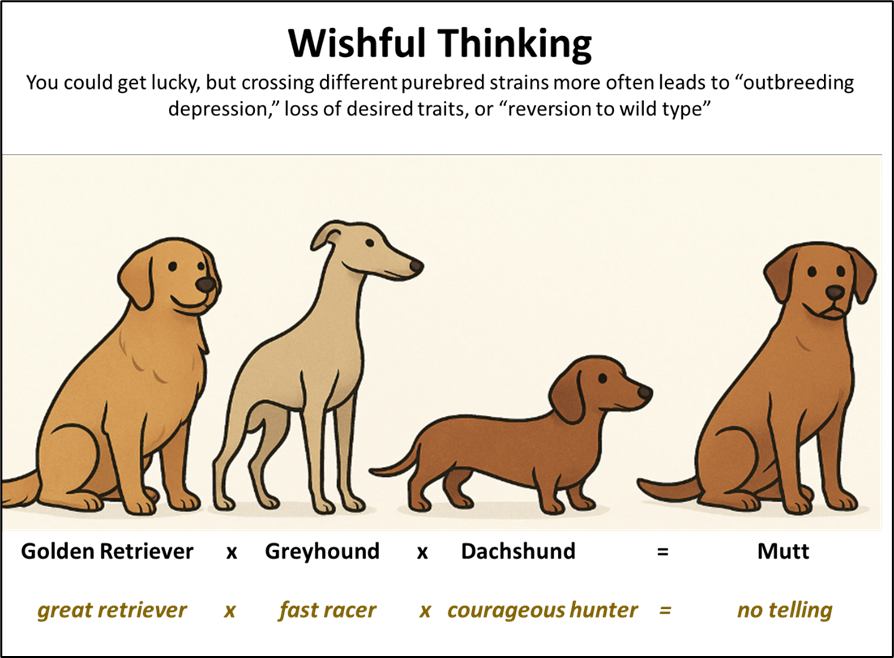

If you feel like gambling, you could try to magically create a new combination of genetics ― by crossing two or more different strains of bees ― to come up with a mite-resistant bloodline. Many of us have already tried that (and wound up with “Frankenbees”), so I wish you luck! (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 Each of these dog breeds have been selected over many generations for specific desirable physiological and behavioral traits (instincts), carried by “coadapted gene complexes” ― groups of interacting genes carrying a specific set of alleles that work together to produce those traits. But there’s no telling what the result will be if you mix them up.

Practical application: It’s a complete gamble to cross different stocks of mite-resistant bees (e.g., any combination of mite biters, Russians, VHS, SMR, or wild-type strains). You could get lucky, but you’re more likely to mess things up.

Option #3 (the one that we took)

See whether you already have any resistant colonies in your operation. If you’ve been controlling varroa with treatments across the board, you’d have no way of knowing. We didn’t know it until when in 2015 we took mite washes from a bunch of hives and discovered Queen Zero. (A large operation might just sample a thousand of their best hives).

If you find that you’ve already got the genetics for resistance existing in your operation, you only need to add “low mite-wash count” to your selection criteria for your breeder queens, and take it from there ― replacing every queen in your operation each year with daughters grafted from the mothers of your best resistant colonies.

Practical application: We started by identifying resistant breeders in our existing operation, and it’s been a long haul. For best progress, perform “progeny selection” by grafting not only from the queens whose colonies performed well, but especially from those that were able to pass those genetics onto their daughter colonies. This requires tracking the queen mothers of each colony, as well as maintaining those breeders for a third year. Tip: Restrict their egg laying, so that they last longer.

Option #4 (the easiest)

Start with a developed stock of resistant bloodlines (emphasis on the plural!).

Step 1. Purchase a whole bunch of production queens from a single proven resistant stock to produce drone-mother colonies. Once they are producing drones, go to Step 2.

Step 2. Purchase a number (to maintain genetic diversity) of breeder queens from the same stock. Graft from them, and mate their daughters out to the drones above.

Update: People ask whether they can buy breeder queens from me. There’s no need to purchase breeder queens. It’s cheaper to purchase a bunch of purebred mated queens (all of which are daughters of selected breeders), which will then not only provide more genetic diversity for your breeding program, but also act as drone mother colonies next season, to provide purebred drones to mate with your queens! Next year just graft from the most desireable and mite-resistant queens that you purchased the previous year, and surround your mating yard with purebred drone mothers.

We are not the only game in town. Although we are proud of our GWB stock, there may be other breeders whose stock (Italian, Carniolan, or mutt) may be adapted to your location and management style (you may wish to ask them for hard data supporting their claim for mite resistance).

Step 3. Replace every queen in your operation with the properly-mated queens from Step 2.

Step 4, Option a. Next year, mite wash every hive in your operation to select at least 25 breeders from the above colonies. (You can make an occasional exception to breed from fewer queen mothers, since every queen’s daughters are sired by a diversity of fathers.)

Step 4, Option b. Or instead, again purchase purebred breeders from the original stock, using your best (and most mite-resistant) colonies as drone mothers.

Step 5. Repeat ad infinitum.

Practical application: You can decide whether it’s more cost-effective for you to perform wholesale mite washes every year, or instead purchase a few breeder queens each year to perpetuate the stock (which would maintain genetic diversity). The key thing would be to manage your drone pool.

HOW MANY COLONIES DO I NEED?

It depends upon how prevalent mite resistance is in your starting stock. For the first several years of our breeding program, only a few percent of our colonies made the grade, so we needed to wash over a thousand hives to identify enough breeder queens to maintain genetic diversity. We still wash every hive in the operation in the first round, not only to identify potential breeders, but to eliminate any queens that we don’t want to be producing drones the next spring (due to high mite counts, spiciness, or non-productivity).

And then you need to maintain enough drone mothers to produce the drones to fertilize your virgin queens. (This initially required us to move 450 drone-mother colonies to Olivarez’s isolated mating yard, until they were able to produce their own.)

Practical application: Face reality: A realistic breeding program requires a lot of hives! Not only do you need hundreds of hives to control the drone pool, but the degree of selective pressure that you can exert is a function of the percentage of your total queen pool that you can eliminate each year. To maintain adequate genetic diversity, graft from at least 25 breeders each year. It’s unrealistic to think that you can maintain a selective breeding program with only a few dozen hives.

HOW SHOULD I CONTROL THE DRONE POOL?

Every bit as important as your queens are the drones with which they mate. Over the years, many queen producers have brought in instrumentally-inseminated mite-resistant queens, only to watch that desirable trait disappear in subsequent generations.

Practical application: It appears that some of the genes involved in mite resistance are recessive, meaning that even if the queen carries the right alleles, those traits won’t be expressed unless she mates with enough drones also carrying those alleles. Managing the drone pool is critical for increasing (or maintaining) the prevalence of the necessary alleles in subsequent generations.

A common question is whether you need an isolated mating yard. Not if you are a large-scale beekeeper, and can flood the area around your mating yards with your own drones. This was established by Hellmich [[4]], who cleverly allowed daughters of double-recessive cordovan queens to open mate in or around commercial queen breeding apiaries Their conclusion was:

We consider 90-95% to be a realistic level of mating control that most queen producers will be able to attain without substantially modifying existing practices.

A 90% control of matings is good enough for me.

Practical application: Although an isolated mating yard or island would be ideal, it’s not necessary if you can flood an area with your drones. But if you’re going to seriously breed for mite resistance, you need to go “all in.” That means that every queen in and around your operation and mating yards must come from the mother of a colony exhibiting resistance.

YOU GOTTA DO A LOT OF MITE WASHES!

Initially, you’ll need to do mite washes in early summer on every hive in your program to identify which colonies score counts of 0 or 1, to label as potential breeders (treating those that don’t). Then perform follow-up counts on the potential breeders every month or so ― eliminating from “competition” any whose counts have gone up (treating them, but perhaps later using them as drone mothers).

Over the years, as your number of “winners” make grade, you can be more selective for your drone mothers. As mentioned above, we initially needed to move hundreds of our own GWB (Golden West Bees) selected drone-mother colonies to the Olivarez (OHB) mating yards to fertilize the virgin GWB queens — which was a real pain. But now OHB has enough yards stocked with purebred GWB colonies, that my son Eric can head down in autumn to oversee taking mite-wash counts from those hives, in order to identify those to be used as queen mothers. This October he washed 1400 hives just to identify potential drone mothers, based upon their strength and productivity (we were impressed by how many made grade).

Note: The above mite washes were only for picking out drone-mother colonies. To choose breeder queens, we perform far more washes in our GWB operation, and track “potential breeders” over the course of a full year. In the last several years of our breeding program, we’ve easily performed over 30,000 mite washes. Happily, it looks as though it’s been worth the work!

Practical application: That 30,000 number may seem like a lot, but keep in mind that it costs less to perform a mite wash than it does to apply a mite treatment (and if performed in the field, a treatment can be applied while the hive is already opened). Doing 30,000 mite washes has actually saved us money. I detailed the equipment that allows us to do this in Part 3 of this series [[5]].

SHOULD I USE INSTRUMENTAL INSEMINATION?

I’m often asked, why aren’t you using instrumental insemination (II)? The answer is that we’re running a K.I.S.S. (Keep it simple stupid!) demonstration project, intentionally requiring nothing more complicated than mite washes. But there’s no need to limit yourself similarly — if you’re proficient at II, then you may be able to speed up your progress by performing single-drone inseminations to lock critical alleles into a bloodline. But you gotta be careful, since single-drone insemination greatly bottlenecks the overall genetic diversity then carried by the resulting daughters and drones from that queen!

Practical application: There’s a reason that virgin queens go out of their way to mate with drones from as wide a diversity of colonies as possible. Evolutionary natural selection found that maintaining genetic diversity (as opposed to inbred bloodlines) results in better colonies.

Although a few species of animals exist as “clonal populations” [[6]], the vast majority of species consist of genetically-diverse individuals. On the other hand, a honey bee colony consists of a team of genetically diverse patrilines of workers. Each patriline carries the same number of genes, but there may be multiple variants (alleles) of any gene (which may be common or rare, recessive or dominant, or pleiotropic), as well as heritable epigenetics. The resulting worker-to-worker differences in instinctual behaviors and physiology generally allows a genetically diverse colony to function more successfully than a group of genetically identical sisters. What this means is that:

SELECTIVE BREEDING IS A BALANCING ACT

If you’re not gambling on creating hybrids, or hoping for mutations, then selective breeding boils down to a process of directed elimination of unwanted genetics ( certain alleles or combinations thereof). But you gotta be careful that you don’t throw out the baby with the bath water! (See Figure 3.)

Fig. 3 Selective breeding is a balancing act. The goal is to maintain genetic diversity in the breeding population’s gene pool as a whole, while eliminating undesired alleles by grafting from only a very limited number of selected mite-resistant breeders each year (we graft from only 2% of our queens).

Genetic bottlenecking due to inbreeding also increases the chance of the expression of deleterious recessive alleles. I couldn’t explain it better than does the American Breeder. [[7]]

Let’s face it — genetic bottlenecks are like kryptonite to any breeding program. They weaken your animals’ health, make them more susceptible to genetic disorders, and ultimately, could lead to the downfall of an entire breeding line. So, how do we avoid this disaster? By focusing on one key factor: genetic diversity. Maintaining a broad gene pool ensures that your breeding program stays strong, healthy, and resilient over the long haul.

Practical application: Rather than focusing on specific bloodlines, focus upon eliminating the prevalence of alleles that allow mites to successfully reproduce, while maintaining the genetic diversity of the rest of the genome of your entire breeding population.

HOW OFTEN SHOULD I BRING IN OUTSIDE GENETICS?

I hear of beekeepers introducing new stock into their “breeding program” on a regular basis, thinking that the introduction of “new” genetics might improve their stock. The grass always looks greener on the other side of the fence (Figure 4).

Fig. 4 You may be tempted to introduce outside genetics into your breeding population, but that’s contrary to the concept of selectively breeding for a purebred strain of bees.

Bringing in new bloodlines is called “outcrossing,” and may be useful to correct the negative results of loss of genetic diversity resulting from excessive inbreeding. But such outcrossing comes with risks — it can dilute the prevalence of your hard-won alleles for resistance, disrupt your established genetic cascades that confer mite resistance, or even worse, result in a “reversion toward wild type” (which, among other things, may result in pissy or nonproductive bees).

Practical application: Stay the course! Once you’ve identified a single productive and fully resistant colony, you’ve got all the genetics you need. Don’t mess it up by bringing in outside stock.

UNDERSTAND THE GENETICS INVOLVED IN MITE RESISTANCE

Note to professional queen producers: The term “genetics” was first used in 1905; the thousands of breeds of plants and animals developed by humans prior to that time were created by simply selecting for individuals that looked or behaved in a certain way. You can do the same by simply seeing whether a colony “gets the job done” by a mite wash. The following section is only for those wanting a deeper understanding (skip it if you wish).

The first thing to keep in mind is that mite resistance all boils down to the bees somehow decreasing the ability of mites to reproduce. (Unless each female mite, on average, produces at least one mated daughter that then successfully invades a cell and reproduces herself, the mite population will decline.)

There are more possible ways that bees can fight the mite than we can imagine, but some well-known ones are grooming/biting, social apoptosis (infested larvae or pupae producing a “sacrifice me” pheromone), hygienic removal of infested pupae (VSH), disruption of mite reproduction via uncapping behavior, modification of the kairomonal cues used by the mite (SMR) [[8]], or the regulation of bee proteins directly used by the mite [[9], [10]].

This means that the genetics involved can be very complex, especially since resistant colonies generally exhibit an array of different mechanisms to suppress mites. And when I say “genetics,” this includes the genome, the epigenome, paternal and maternal effects, and who knows what else.

Genetics are nothing but a set of instructions. Some genes code for proteins, such as an olfactory receptor protein that might bind to an odor produced by a mite, or for a pupal pheromone to which a mite responds. Other genes are involved in unbelievably complex regulatory cascades, which then trigger physiological and/or behavioral responses. Selective breeding is all about developing and fine-tuning the genetics of a biological working system — in this case a honey bee strain that is workable, productive, and resistant to varroa.

We are selectively breeding not only for genetic expression of biochemistry and organismal physiology, but also for a combined suite of specific behaviors cemented into “instincts” [[11]]. When breeding for mite resistance, bees need to have structural gene alleles that code for specific olfactory receptor proteins (so that they can detect mites), as well as regulatory cascades that initiate behavioral responses to the mite, including grooming, uncapping, or varroa-specific hygienic behavior. There can also be regulation of the pheromones or proteins that mites respond to, or even self-sacrifice (social apoptosis) in response to the mite [[12]], or even heritable epigenetic factors [[13]].

Similar to how a car is a fine-tuned system of parts and electronic control units that work in harmony, in which you swap parts at great risk, when you’re breeding a strain of honey bees, you’ve selected for a package of structural (maybe 5%) and regulatory genes (those that code for physiological responses or instinctual behaviors) that all work together in a “co-adapted gene complex.” Don’t mess with it (Figure 5).

Fig. 5 When you introduce unrelated stock to your breeding population, the result is more likely to result in system malfunction rather than improvement.

Practical application: Once you’ve got a selective breeding program underway, don’t throw a stick into the gears! Avoid the temptation to introduce new genetics.

Update: In response to an email about crossing stocks exhibiting resistance by instrumental insemination, I responded:

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Ten years into our demonstration project for selective breeding for mite resistant bees, the light at the end of the tunnel is now shining brightly. It brings a smile to my face to see quintuple-zero-count hives being the best producers in the yard — beekeeping as it “used to be.”

Practical application: My problem these days is often finding enough hives with high mite counts for me to test experimental treatments on.

In the words of the Roman orator Cicero: Plant trees for the benefit of future generations [[14]]. Let’s all work together to put an end to “The Varroa Problem,” not only for ourselves, but for tomorrow’s beekeepers.

CITATIONS AND NOTES

[1] https://kirkwebster.com/11-december-conclusion/

[2] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/queens-for-pennies/ (March 2014 ABJ)

[3] https://scientificbeekeeping.com/small-scale-queenrearing/

[4] Hellmich, R & G Weller (1990) Preparing for Africanized honey bees: Evaluating control in mating apiaries. ABJ 130(8): 537-542.

Hellmich, R, et al (1993) Evaluating mating control of honey bee queens in an Africanized area of Guatemala. ABJ March 207-211.

[5] See October 2025 ABJ. You can buy the mite wash cups and battery-powered agitators from Jacob McBride at forbeessake@gmail.com

[6] Avise, J (2015) Evolutionary perspectives on clonal reproduction in vertebrate animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(29): 8867-8873.

[7] https://www.americanbreeder.com/resources/american-breeder-blog/dogs/prevent-genetic-bottlenecks-breeding-programs

[8] Frey, E, et al (2013) Activation and interruption of the reproduction of Varroa destructor is triggered by host signals (Apis mellifera). Journal of invertebrate pathology 113(1): 56-62.

[9] Conlon, B, et al (2019) A gene for resistance to the Varroa mite (Acari) in honey bee (Apis mellifera) pupae. Molecular Ecology 28(12): 2958-2966.

[10] Aurori, C, et al (2021) Juvenile hormone pathway in honey bee larvae: A source of possible signal molecules for the reproductive behavior of Varroa destructor. Ecology and Evolution 11(2): 1057-1068.

[11] Robinson, G & A Barron (2017) Epigenetics and the evolution of instincts. Science 356(6333): 26-27.

[12] Zhang, Y & R Han (2019) Insight into the salivary secretome of Varroa destructor and salivary toxicity to Apis cerana. Journal of Economic Entomology 112(2): 505-514.

[13] Sarkies, P (2023) Evolution beyond DNA: epigenetic drivers for evolutionary change? BMC Biology 21(1): 272.

[14] Serit arbores quae alteri saeculo prosint.