Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance Part 2: Concepts

December 29, 2025

Contents

BEES ARE DIFFICULT TO SELECTIVELY BREED! 3

DARWINIAN BLACK BOX SELECTION 4

IMAGINE SELECTIVE BREEDING AS A CARD GAME 7

Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance

Part 2: Concepts

First Published in ABJ September 2025

Randy Oliver

ScientificBeekeeping.com

Left to its own, the process of natural selection will favor bee bloodlines that are resistant to varroa. But we beekeepers have hamstrung that process by artificially controlling varroa with miticides, thus allowing non-resistant colonies to continue to propagate. Until our commercial queen producers all get serious about selective breeding for mite resistance, we’re going to be fighting varroa — and dealing with miticide resistance — for the rest of our lives.

The natural process of evolutionary selection is an ongoing cost-benefit analysis of random combinations of genetics. Introduction of a novel parasite changes the costs — colonies that can’t control varroa are unable to get their genetics into the next generation. If we artificially control varroa (which eliminates that cost), it thus behooves us beekeepers to recognize our responsibility to then work with nature to apply that cost (via queen selection) — without the need for any colonies to die! The good news is that it’s not that hard for a queen producer to do!

LET’S GET REAL

Many queen producers have taken a stab at producing resistant stock by purchasing breeder queens and hoping for a miracle (been there and done that), but found it difficult to maintain resistance. Some, myself included, have made unrealistic or half-assed attempts at selecting for mite resistance. The problem is that most found it too difficult or costly to maintain a realistic selective breeding program for mite resistance — it’s much easier to breed for color, gentleness, or honey production. And anyway, since one could sell all the queens they could produce, there was little incentive to make the effort.

Practical application: Selective breeding is not a “one and done,” but requires annual selection of breeder queens, based upon assessment of their untreated colonies’ abilities to keep mites in check, as well as sustaining a drone pool carrying the critical genetics. Until the consumer rewards the queen producers for offering resistant stock, we’re not likely to see our situation change!

When we performed our first large-scale mite washes back in 2015, I was surprised to find “Queen Zero,” whose colony required no help to keep varroa in check [[1]]. Oh my gosh — I realized that all the genetics necessary for mite resistance were already present in my own stock! No need for a miracle, what I realized was that it was time for me to get serious, and figure out how to perform thousands of mite washes each and every year. I did so, and decided to run an experimental demonstration project of the most simplified selective breeding program possible — for the benefit of all professional queen producers — keeping track of how much it cost, and whether it could be successful [[2]]. My goal was to take away any excuses for them not breeding for mite-resistant stock themselves.

Since then I’ve published annual updates on our progress. There’s nothing new about the concept of our program; it’s nothing but the type of “old-school” selective breeding that humans have practiced for centuries — long before the words “genetics” or “science” were even invented (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Back in the day, if you wanted to select for gentle stock, you simply requeened any “hot” colonies with a daughter of a queen whose colony was “gentle.” No complicated assays, and no colonies needed to die.

Practical application: There’s no need to understand exactly how mite-resistant colonies do it, so long as they do it! Just give them the job description, and promote those that get the job done. No mites: breed from her; too many mites: requeen. K.I.S.S.!

BEES ARE DIFFICULT TO SELECTIVELY BREED!

I didn’t say that it was gonna be “quick and easy.” Honey bee reproductive biology is all about maintaining genetic diversity in the breeding population — which is non-conducive to selective breeding for a specific set of genetics.

Let’s look at why the selective breeding of bees far more difficult than for most other animals.

- A queen mates with many drones (polyandry) — under natural conditions grabbing some of the genetics from every successful colony in the neighborhood. This allows her to produce a colony which consists of a team of workers with great genetic diversity — which may result in a team that is a winner or a loser (in general, the more genetic diversity in the workers, the better a colony functions).

This also helps to maintain genetic diversity in the breeding population after a natural disaster or novel pathogen that wipes out most of the colonies in an area, since any surviving colony carries the genes not only of their mother, but also from all the drones that she mated with. The problem with this with regard to selective breeding is that half the genetics carried by any open-mated queen come from a diversity of sources (depending upon how well the breeder can control the drone pool).

- That said, we’re not selecting for the performance of the queen, but rather for the performance of her team of daughters (an outcome that may be only be partially heritable).

- Since the drones carry only the genes of their mothers, that means that the genetic diversity of the drone pool reflects that of their grandparents’ generation — resulting in a two-year lag in a breeding program.

- Bees mix it up. The honey bee exhibits an extremely high rate of genetic recombination during the process of meiosis (the formation of egg or sperm cells), where sections of DNA are exchanged between a parent’s two chromosomes or parts of the same chromosome. This exchange results in new combinations of genetic material, creating offspring with traits different from their parents, which allows for rapid evolution.

- Not all mutations or recombinations of alleles work well together, so the honey bee winnows out deleterious alleles or bad combinations via the haploidy of the drones. Since the drones carry only a single set of chromosomes, they can’t be rescued from carrying deleterious alleles by the presence of “good” alleles that they got from another parent. This is good in a breeding program (dog breeders, due to inbreeding, are plagued with this problem).

- And perhaps the most limiting factor as far as selective breeding, is the sex determination gene, which prevents a breeder from mating a queen with a close relative. In selective breeding, the mating of closely related individuals (inbreeding) is a common practice. Inbreeding allows the breeder to “fix” specific traits into predictable “purebred” bloodlines. But in honey bees, one must maintain the genetic diversity of the sex alleles, or you’ll get queens that produce spotty brood.

Practical application: All the above make it far more difficult to selectively breed bees than to breed strains of cattle, dogs, or plants. We are selecting for colony performance, rather than that of individuals, must shift the genetics of an entire breeding population, rather than specific bloodlines.

DARWINIAN BLACK BOX SELECTION

As I explained last month, we know some of the ways that colonies can use to fight the mite, but no one knows them all. Luckily, there’s no reason that we need to understand them all in order to breed resistant stock. This concept was clearly explained by Blacquière back in 2019 [[3]]:

Here, we use the analogy of a black box from which the content remains hidden while the obvious effects of this content are nonetheless clear and visible. Moreover, the route does not beforehand qualify certain traits thought to be of advantage, but just follows nature to the outcome of survival and reproduction. Inside the black box, alleles associated with a successful phenotype are conserved and will persist in the next generation. Natural selection is therefore ‘inclusive’ as it maintains genetic diversity by keeping all surviving phenotypes in the black box, including possibly rare alleles beneficial for resistance to parasites and pathogens. Targeted selective breeding programs, on the contrary, are by definition reducing genetic diversity by selecting from the surviving phenotypes only those of their preference of chosen traits, thereby potentially excluding many of the phenotypes despite their shown capability of survival.

Practical application: Forget targeted selection for specific traits! The job description is for the colony to keep mites in check by any means. Fire those that don’t, and promote those that do. The only selection criterion necessary is mite counts.

IT TAKES A TEAM

There’s no such thing as a mite-resistant queen — it’s up to the workers in a colony, working as a team, to control the mites. The workers are not clones of their queen mother, but rather a team of different patrilines. Since the queen carries two sets of chromosomes (one from each of her parents), half the workers in each patriline of (fathered by one of the drones that the queen mated with) will carry the genetics of that drone’s maternal grandmother, and half will carry those of his maternal grandfather. This means that if a queen mates with 15 drones, there will be 30 different genomic lines of workers in the colony — any of which may or may not be involved in mite resistance.

Think of each different patriline of daughters as a group of similar “players” on the team. Some will reflect the genetics of the mother, some of their father. Some may be sensitive to mite or brood odor, some may uncap infested brood cells, some may have strong hygienic or mite-biting behaviors, and some may express pheromones that screw up mite reproduction. It may not be a particular bloodline, but rather the team as a whole that wins the game (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 In a breeding program, we can select certain queens, but must keep in mind that that there’s no such thing as a mite-resistant queen. Mite resistance is a team effort by the colony, with each line of workers exhibiting different behaviors, sensitivities or pheromone production, or specializing in different tasks [[4]]. As pointed out by my recently-departed friend Peter Borst, producing daughter queens from the mother of a “winning” resistant colony is akin to hoping that the offspring of a randomly-selected single player of a winning basketball queen will form a winning team of their own.

Practical application: You can purchase a daughter of the queen mother of a mite-resistant colony. But it’s then up to the team of granddaughters of the breeder queen working together as a team to fight the mite. But those granddaughters have a bunch of different fathers. It’s thus critical that the drone pool comes from other “winning teams” — other resistant colonies using the same mechanisms for resistance.

IMAGINE SELECTIVE BREEDING AS A CARD GAME

Every honey bee carries the same set of genes (~10,000 carried on 16 pairs of chromosomes) — some “coding” for a specific protein, but the majority involved in one or more regulatory functions. And some genes are “pleiotropic,” meaning that they can influence multiple, seemingly unrelated traits.

Each female bee (a diploid queen or worker) carries two sets of chromosomes — one set from her mother, the other from her father. Each drone (being haploid) carries only one set, coming (via their mother) from either their grandmother or grandfather (perhaps with some recombination). Thus the workers of the colony as a whole carry a wide diversity of combinations of the chromosomes originally coming the queen’s mother and father, and the grandparents of every drone that the queen mated with.

Let’s imagine a greatly simplified analogy, in which the genetics of a honey bee are represented by a straight run of 14 playing cards (ace through king, plus a joker), each card representing one gene. The jokers could represent pleiotropic genes. And each gene can come in different forms, called variants or alleles — for this analogy, think of the suit (spades, diamonds, etc.) representing a different allele of that gene (e.g., some bees carry the seven of clubs, others the seven of diamonds).

Now imagine that the 10 through ace represent the genes involved in mite resistance, with only the heart suit being the allelic form conferring resistance. All the rest of the cards in the run code for other aspects of behavior or physiology, their various suits representing genetic diversity (which we wish to maintain).

No one yet knows how many of those face cards in the heart suit it takes to cause an individual bee to perform one aspect of mite resistance (such as uncapping or VSH behavior), nor whether a bee needs to inherit two copies of a heart face card (for a recessive allele), nor how many patrilines of workers in a colony must carry those heart alleles to allow the colony as a whole to exhibit resistance. But if the colony’s queen has by chance been dealt a winning hand by the combination of genes inherited from her parents (Figure 3), all the workers of the colony would carry at least one copy of each heart face card for resistance.

Fig. 3 The royal flush of genetic alleles to confer mite resistance. All the rest of the cards, of mixed suits, provide genetic diversity for all other functions and traits. If we can get a queen carrying a pair of royal flushes in hearts, she would likely “breed true,” with at least half of her daughter colonies exhibiting resistance (dependent upon the drones that she mates with).

Practical application: A resistant colony must contain the components of a royal flush in hearts scattered among its workers. But our aim is to get queens that carry that royal flush in hearts themselves.

A selective breeding program does not “breed in” mite resistance, but instead “breeds out” any alleles that are non-resistant (get rid of face cards in other suits), while at the same time maintaining a diversity of suits in the rest of the deck. To “breed true,” a resistant bloodline of queens must only carry face cards in the suit of hearts (at this point, the alleles for resistance would be termed “fixed” in that bloodline).

But no matter how true the queen’s bloodline, unless you perform instrumental insemination or find an isolated mating yard, every virgin queen will open mate with a drone pool consisting of the cards from perhaps dozens of different decks.

Practical application: Our goal is to fix the heart alleles for the complete royal flush in our entire breeding population in order to reliably produce queens that “breed true.” We’re not there yet.

We’ve clearly got the alleles for royal flushes in hearts scattered throughout our breeding population, but there are apparently still a lot of face cards in suits other than hearts remaining — which is apparently why the daughter colonies of breeders are so hit or miss (there’s apparently still a lot of luck involved in getting them all into the same queen). We need to continue to “weed out” the non-heart face cards. But every year our chances improve at being dealt winning hands.

IT’S A BALANCING ACT

Any time you start a breeding population with a limited number of individuals, there is a “founder effect” — meaning that the diversity of cards left in the deck is less than that of the original breeding population. And by definition, a selective breeding program favors certain genetic alleles over others, thus decreasing the “genetic diversity” of the breeding population.

There’s good evidence that genetically-diverse colonies function better, and are more disease-resistant than are inbred ones [[5]], so we must pay attention to maintaining genetic diversity.

This potential problem is termed “bottlenecking” or “genetic drift.” Such genetic drift is not necessarily a bad thing — breeding for bees that don’t sting the snot out of you results in the loss of alleles for extreme defensiveness, but can leave the rest of the genome unchanged.

So we must be careful not to lose favorable alleles, or to inadvertently promote deleterious ones. Dog and livestock breeders are acutely aware that genetic bottlenecking is like kryptonite to any breeding program. But with honey bees we’d quickly notice severe inbreeding, due to the effect of the sex determination gene, which would result in spotty brood from diploid drones. The subject of closed-population bee breeding was addressed years ago in a number of papers by Rob Page [[6]].

Keep in mind that unlike animals in most breeding programs, we’re breeding for colonies of a diverse group of workers who function as a team. Over the long term, we want all the teams to carry the royal flush for resistance, but maintain diversity in their many other genes.

Practical applications:

- The need to strike a balance: In a breeding program, you must balance the genetic bottlenecking caused the limited number of colonies that you breed from, against the need to maintain adequate genetic diversity within your breeding population as a whole.

- Graft from enough queens: The smaller your breeding population (and number of queens that you graft from), the greater the chance of losing critical genetic diversity. So breed from a number of queens each generation. I can’t give an optimum figure, but based upon my interpretation of Rob Page’s modeling, our rule of thumb is to graft from at least 26 queens (named A through Z) each spring, favoring of course, some a bit more than others.

- Using top crossing: Unless you’re using instrumental insemination, the open mating of your queens to your drone pool is called “top crossing.” Top crossing is a method commonly used by plant and animal breeders where a superior performing individual is crossed to a large number of other individuals within the breeding population. This method allows for rapidly increasing the frequency of desirable characteristics within breeding populations, while maintaining genetic diversity.

- Reality Check: Due to the importation of many strains of honey bees prior to 1922 [[7], [8]] our North American honey bee population is more genetically diverse than that of any strain in their native populations [[9]]. Although the vast majority of managed bees are of central European heritage, and targeted breeding can reduce genetic diversity [[10]], there is always some degree of introgression of outside genetics into any managed breeding population (other than closed populations maintained by isolation or instrumental insemination). The combination of random mutation, coupled with a trickle of genetic introgression from the occasional “foreign” drone, may be enough to maintain adequate genetic diversity.

OUR PROGRESS TO DATE

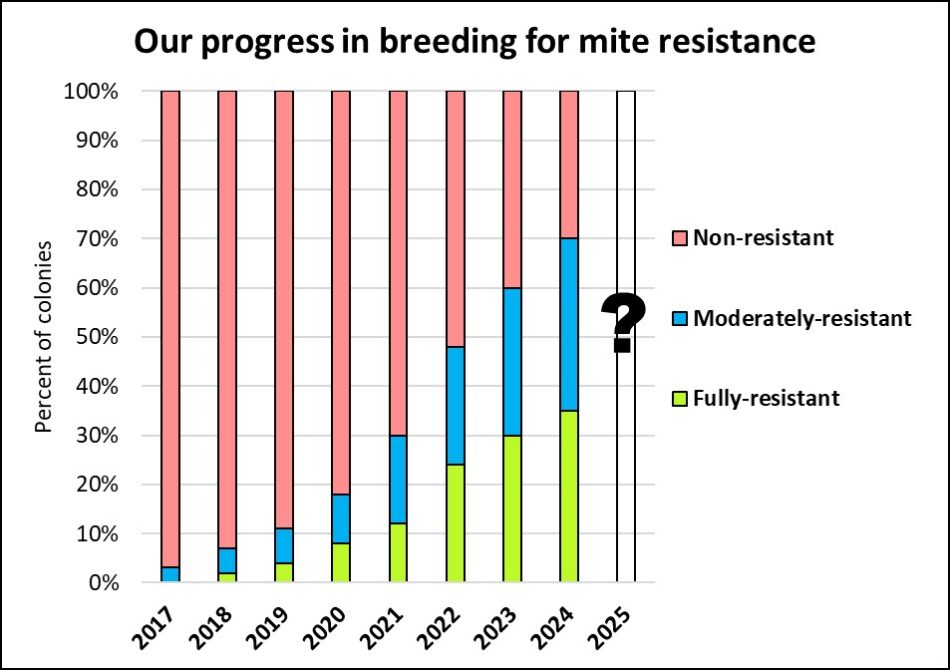

Fig. 4 After nine years of strong selective breeding, we’ve gone from one colony out of 1500 needing no mite treatments, to over a third (that’s over a 300-fold increase). So we’re not quite “there,” but with the majority of our colonies now exhibiting some degree of resistance, it’s no longer difficult for us to maintain healthy colonies using only “natural” treatments.

Note in the above chart how the proportion of drones coming from non-resistant colonies is decreasing each year (despite the ingrained 2-year lag). We’ve yet to see what happens when the drone pool passes the 50% level for resistance.

JULY UPDATE

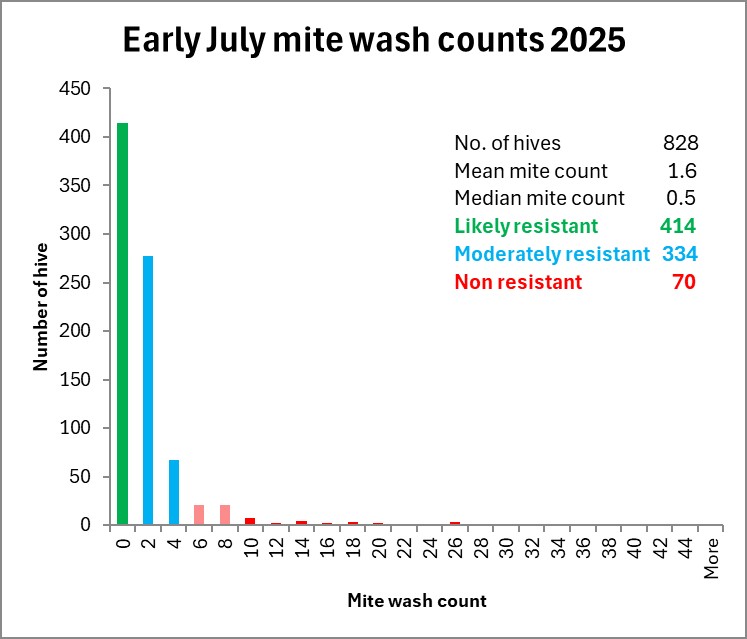

The guys just performed our first mite-wash counts for our first-year colonies — about half as many as we normally have at this time, due to our colony losses due to the dwindling disease last fall, and after selling a thousand nucs (Figures 5 & 6).

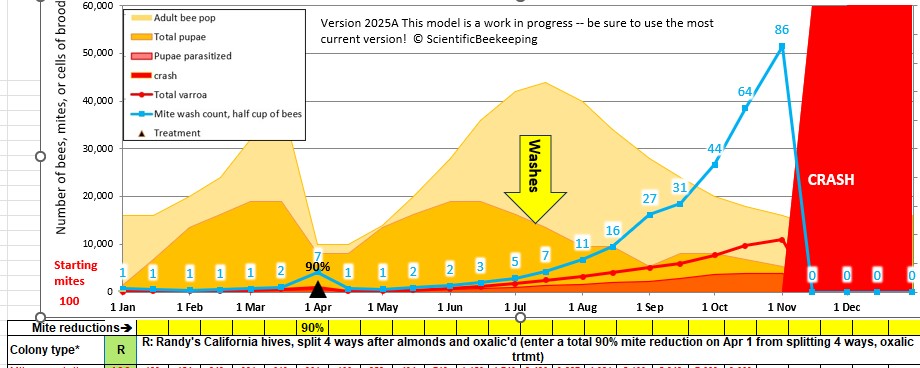

Fig. 5 When we began our breeding program, our expected average mite wash count in early July would have been around 6 mites in a half cup of bees. But things have changed…

Fig. 6 Above is this year’s distribution histogram of early-July mite-wash counts for our 828 first-year hives held in 25 different yards (the rest of our yards are filled with second-year colonies). These hives were from nucs started in late March and early April, given a single oxalic acid dribble at that time. Note that over three months later, a handful of outlier hives had counts in the 20-40 range (showing the potential for mite reproduction), but half the hives showed mite wash counts of zero.

We treated any hives with counts above 1, and of course don’t know how many more will require treatment toward fall (or might have taken their count down by themselves), but since we began our selective breeding program, mite management has gotten a heckuva lot easier and cheaper! (It cost us less for the labor to perform the mite washes, than it would have cost us to unnecessarily treat those zero-count colonies).

Practical application: Stop complaining about varroa! Supply follows demand. Ask yourself, how much more is a queen worth, if she saves you the cost of mite treatments? Nothing’s gonna change until the buyers of queens start demanding (and paying for) stock that can handle varroa on its own, and all queen producers start posting histograms like the one above. Next month I’ll show how to do it.

CITATIONS AND NOTES

[1] The Varroa Problem: Part 7- Walking the Walk. https://scientificbeekeeping.com/the-varroa-problem-part-7/ (ABJ, May 2017)

[2] Selective Breeding for Mite Resistance: 1000 hives, 100 hours. https://scientificbeekeeping.com/selective-breeding-for-mite-resistance-1000-hives-100-hours/#_edn3 (ABJ, March 2018)

[3] Blacquière, T, et al (2019) Darwinian black box selection for resistance to settled invasive Varroa destructor parasites in honey bees. Biological Invasions 21(8): 2519-2528.

[4] Perez, A & B Johnson (2019) Task repertoires of hygienic workers reveal a link between specialized necrophoric behaviors in honey bees. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 73: 1-12.

[5] Desai, S & R Currie (2015) Genetic diversity within honey bee colonies affects pathogen load and relative virus levels in honey bees, Apis mellifera L. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 69: 1527-1541.

[6] Page, R & H Laidlaw (1985) Closed population honeybee breeding. Bee World 66(2): 63-72.

[7] Carpenter, M & B Harpur (2021) Genetic past, present, and future of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) in the United States of America. Apidologie 52(1): 63-79.

[8] The Honeybee Importation Act https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/7/281

[9] Harpur, B, et al (2012) Management increases genetic diversity of honey bees via admixture. Molecular Ecology 21(18): 4414-4421.

[10] Saelao, P, et al (2020) Genome-wide patterns of differentiation within and among US commercial honey bee stocks. BMC Genomics 21(1): 704.