Oxalic Acid Dribble and Sublimation Updates

Update 28 Oct 2018

Beekeeper Nick Kingan let me know that there’s a nice livestock syringe available from Tractor Supply that can be adjusted to dispense 5 mL per squeeze. I find the squeezing of this sort of syringe to be tiring to my hand if I’m treating a large number of hives, but it may be handy for those with just a few hives, since it helps to dispense the correct dose.

Update 20 Sept 2017

dihydrate for each five deep for eight consecutive weeks this summer. I had ten nucs untreated side by side for controls. The single highest

after treatment mite count was from a treated nuc determined by alcohol wash at 3%. I saw exactly zero evidence that I killed any significant number of mites. Overall the treated hives and controls had equivalent mite counts. All were at 0 to a bit over 1% mites at the start. I dosed as high as 2g/ five deep nuc and showed no adverse effects other than a few burned bees that hit the fogger screen. Fogging ran from mid June

to late July. All were treated earlier in the spring to drive mite counts to about zero with apivar. The slow build up by early August is because I run Minnesota Hygienic queens which do a fair job of containing mite populations.I was pretty careful in the experiment. I spent several hours fooling with the fogger to figure out how to deliver a consistent dose. I had to drill a hole in the top of the handle and push down the trigger fully down with a screw driver after each shot to get consistent volume each time. I also had to pull the trigger as fast as possible to get consistent volumes. I showed, by capturing and analyzing the fog that oxalic was surviving the fogging experience at least partly intact. My capture was under 100% and analysis showed a recovery of 60% so I feel was I was not

decomposing enough to matter.I also waited 20 seconds between trigger pulls to allow full heat recovery in the coil. Even then a lot of what came out the spout was liquid that ended up on the bottom of the nuc. I found the process tedious and not really all that fast at over three minutes per nuc each treatment.I have seen the you tube vids and seen much discussion on fogging. I am the first, as far as I can tell, to ever do before and after mite counts and include controls of any type. At this point I view all such claims as pure snake oil of the usual value that snake oil typically has but am open to being proven wrong. I am a bit leary of firing alcohol due to flammability althou no one has reported a fire issue. [I would expect a fog of alcohol in air to be highly explosive, but I don’t have a heat fogger with which to test. If any reader has tested this, please let me know]

Update 18 March 2017

When OA dribbling package bees (or perhaps any bees), I’ve received a report from a good source that the bees tolerate the dribble better if they are full of nectar or sugar syrup–presumably because they are then less prone to imbibe the OA syrup.

Update 24 Jan 2017

There has been lots of response to my article on OA/gly in ABJ (soon to be posted to this website). I’m in communication with EPA to get this application method approved.

Update 22 Dec 2016

Be sure to check my article in Jan ABJ on OA/glycerin https://scientificbeekeeping.com/oxalic-shop-towel-updates/. I’ll try to post soon.

In response to questions about adverse effects on queens:

The evidence that I’ve seen to date indicate that vaporization does not have serious effects on the queen. On the other hand, there are indications that repeated dribble may.

Update 16 June 2016

I recently received an email from a Northeastern beekeeper, Erik Donley, about his experience with applying oxalic vapor to newly-hived package bees. Excerpts follow:

* I installed 10 x 3LB packages (from OHB) in single deep hives. (April 17th) All but one hive had fully drawn out comb. (The 1 was starting with 1 drawn comb and 9 bare foundations)

* On the 8th day after installation I administered the OA treatment. I vaporized approx .75g (between 1/4 and 1/8 teaspoon) of OA into each single deep hive. (I felt that was a reasonable dose given a full 2 deep hive takes roughy 2g)

* I checked the hives 4 days after and everything seemed fine. All continued to have laying queens with solid brood patterns, there were no issues with absconding, or mutiny vs the queen.

* Since installation, the hives have moved to multiple locations across Northern Minnesota and Wisconsin and have been exposed to a variety of difficult weather conditions. (We had snow and freezing temperatures in late May). Thus the robustness of each hive has been slightly weather dependent, but it appears so far they are not populated with Mites.

Erik is planning to follow up with late summer caging of the queen, followed by another formic vaporization–I will post his results. Note: keep in mind that repeating treatments without rotation, will tend to breed for resistant mites. Better to rotate treatments (such as with thymol). Erik questioned me on this:

A reference from X said that due to the mode of action of OA, it is impossible for mites to gain resistance to it.

My friend Rob Stone (Pierce Beekeeping) recently treated treated a number of packages of bees for sale by spraying a total of 30mL of “weak” solution divided over the four sides of the package cages, and was happy with the results.

Original post

Following the lead of many other countries, EPA has finally approved its legal use for control of varroa. My sons and I have been using oxalic dribble for 15 years with great success. We really like the dribble method due to its low cost, ease of use, safety to the applicator, minimal adverse effects to the colony, and its high efficacy against varroa if applied correctly. Here are some tips:

Application

- The typical dosage of oxalic dribble is 5 mL (1 tsp) per “seam” of bees between the frames. Solution spilled on the top bars doesn’t count. I suggest applying it carefully in order to best distribute it throughout the hive.

- Although some researchers caution about applying more than 50 mL per colony, we routinely treat every seam of bees, even if it takes close to 100 mL total (we may get away with this because our broodless period in the California foothills is very short).

- For application to only a few hives, use a teaspoon or 60 mL syringe (from any feed store).

Dribble being applied with a 60 mL syringe.

- For commercial use, we use a garden sprayer set to a gentle stream, calibrated by the use of a graduated cylinder, to dispense 5 mL per second (1 seam of bees per second, less than 20 seconds per hive).

Calibrating the output of the stream to 5 mL per second. Tip: maintain a large reservoir of air above the liquid–this will reduce the amount of fluctuation in the flow. With practice, it is easy to eyeball the correct stream.

- In fall, we treat the bees in both brood chambers. If the cluster is mainly in the lower box, we tip the upper box back and apply the oxalic from below. If the cluster is mainly in the upper box, we take off the lid and dribble each box from above.

I’m applying the fall treatment while Eric tips back the upper box. We often work in three’s, with two cracking and one squirting.

Treatment windows

- You’ll get the highest efficacy against varroa if oxalic dribble is applied when there is no sealed brood present. This opportunity occurs as a result of natural or induced brood breaks.

- In temperate regions, natural brood breaks typically occur in November through early December.

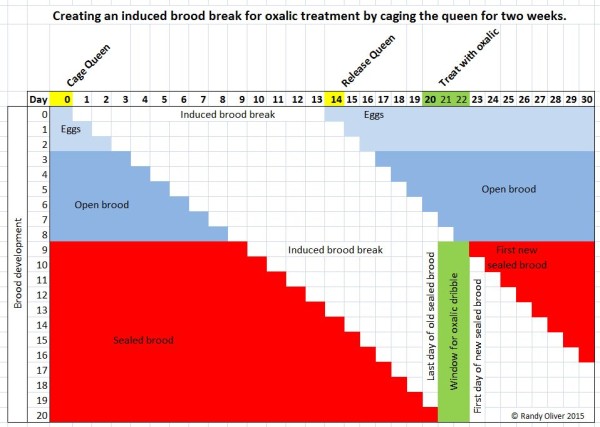

- Alternatively, you can induce a brood break by making shook swarms, or by caging the queen for 14 days, as shown below.

By caging the queen for 14 days, you can create a 2-day window in which there is no sealed brood in which varroa can hide. Note that this window occurs starting about 6 days after you release the queen.

Package bees: Aliano and Ellis, in their very well done preliminary investigation into treating package bees with oxalic, found that the spray application of 3 mL of 2.8% (w:w) of oxalic acid in sugar syrup per 1000 bees resulted in very high varroa kill, with minimal bee kill. Since there are roughly 3500 bees per lb, that works out to:

21 mL of 2.8% OA syrup per 2-lb package,

31.5 mL per 3-lb package, or

42 mL per 4-lb package.

The 2.8% solution is roughly the same as the “weak” formula at Treatment Table. The authors note, however, that their results were preliminary, and I haven’t seen any follow-up research. If you do treat some packages, please let me know the results!

Alternatively, although you could directly treat bees in a package, I’d suggest installing them normally, and then treating them in the hive between Days 5 and 7 after installation. The timing is due to the fact that even if the queen starts laying eggs the day after installation, it wouldn’t be until Day 9 that the first brood would be of suitable age for mite invasion. Oxalic dribble kills mites for roughly 3 days after application. Thus, if you dribble the recently-installed package on Day 6, the full effect of the treatment will have taken place prior to the first opportunity for the mites to hide in the brood.

You can also use this method with shook swarms, or for any divide made without brood.

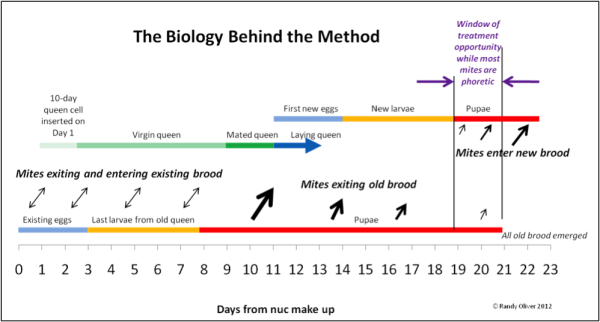

Nucs: Starting nucs with queen cells in spring presents a great opportunity for controlling varroa by dribbling on Day 19. We’ve now used this method on thousands of nucs, and really like it for getting a “clean start” each spring.

Figure 1. The theory behind the early treatment of nucs—it’s all about timing! There is a brief window of opportunity from Day 19 to Day 21 after make up in which every mite in the nuc is forced out of the safety of the sealed brood. A short-term treatment applied at that precise time could result in a very effective kill of the now-exposed mites!

I’ve fully described this method at https://scientificbeekeeping.com/simple-early-treatment-of-nucs-against-varroa/ .

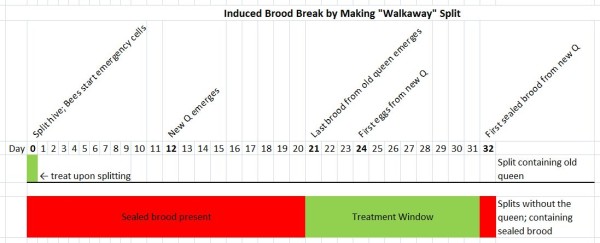

- An even simpler method is to make “walkaway splits”–that is, splitting a hive (into two or more splits) and allowing the queenless split to raise a new queen (although I do not particularly recommend this method, since it depends upon the splits raising emergency queens, plus the splits go without any new brood production for at least 24 days, during which laying workers may develop). The key is to make up the split containing the old queen without any sealed brood (so that all the mites are exposed to treatment). Leave this split on the parent stand to pick up the field force. Into the other (queenless) split(s), place all the sealed brood (any open brood is also fine), along with most of the bees (since all the field bees will fly back to the parent stand). Treat the split with the old queen on the day you make the split(s). Treat the queenless splits on any day from Day 21 through Day 30.

Summer treatment

- Oxalic dribble is not as effective when colonies contain brood (as during spring or summer), but colonies at that time do appear to tolerate stronger or repeated doses due to the rapid turnover of the adult population at that time of year.

- I don’t have data on efficacy, but I’ve treated colonies once a week for three consecutive weeks in late summer without noticing adverse effects (although we prefer thymol or formic acid at that time of year).

Mixing, safety, and storage

- There is a narrow range of dosage that will kill varroa without harming the bees. Follow mixing and application rates meticulously; see https://scientificbeekeeping.com/oxalic-acid-treatment-table/.

- Use common sense when handling oxalic acid crystals. Wear glasses in case of a mishap—you don’t want to get it into your eyes! Wear latex or nitrile gloves to remind you not to rub your eyes.

Weigh the oxalic acid crystals carefully–they cannot be accurately measured by volume (such as by teaspoon measurement).

Note: The wood bleach shown above is not approved for use in bee hives. The only forms of oxalic acid approved for application as a miticide are those registered with the EPA. It is not legal to apply any OA that does not have a label approving it for application for control of varroa.

- Oxalic acid is a relatively strong acid, and is more dangerous to handle than lemon juice or vinegar. You should wear the recommended protective clothing, gloves, and eye protection.

- Based upon my extensive experience with handling OA, wearing safety glasses is the most important, since you definitely don’t want to get it into your eyes!

- The label is the law. That said, I find the recommended glove thickness to be excessive. I’ve found that it’s not big deal when I’ve gotten either the crystals or solution on my skin for a few minutes, and that it can be easily washed off with water. We always keep a jug of neutralizing solution on hand — 10 heaping tablespoons of baking soda dissolved in a gallon of water (the necessary concentration experimentally determined by me). This solution will immediately neutralize any OA (or formic acid) on your skin, protective gear, hive tool, and smoker.

- I do not recommend this, but if I suspect that there is some oxalic syrup on my skin after washing up, I taste my skin with my tongue (OA solution tastes like strong lemonade) just to be sure. This may seem foolhardy, but I can get a dose of up to a full gram of OA in a serving of spinach.

- If your water is hard (contains calcium), use distilled water instead (calcium will cause some of the oxalic acid to precipitate as white calcium oxalate).

- We prefer to first completely dissolve the crystals in hot water, and then add the sugar.

- Oxalic acid in a sugar solution will eventually form HMF [[a]], which is somewhat toxic to bees. It’s unlikely that enough will be formed under normal use to harm the bees, but you should not use a solution that has begun to turn brown. Oxalic syrup can be stored for many months if kept refrigerated [[b]].

[a] Hydroxymethylfurfural, non toxic to humans; commonly found in cooked jams and jellies.

[b] Prandin, L, et al (2001) A scientific note on long-term stability of a home-made oxalic acid water sugar solution for controlling varroosis. Apidologie 32: 451–452. Open access.